Pull your hammy? Strain your quad? Well, it looks like you are out of commission for a couple of weeks!

If the muscle strain is severe, you could be out for months.

You’re probably thinking:

- “What caused the strain in the first place?”

- “Is there anything I can do to get back into play faster?”

- ”How can I make sure this doesn’t ever happen again?”

Pull your hammy? Strain your quad? Well, it looks like you are out of commission for a couple of weeks!

If the muscle strain is severe, you could be out for months.

You’re probably thinking:

- “What caused the strain in the first place?”

- “Is there anything I can do to get back into play faster?”

- ”How can I make sure this doesn’t ever happen again?”

You’re not alone. This article targets how muscle strains happen, what you should do to recover, and how to prevent future strains.

The Dreaded Muscle Injury

Your muscle is a pretty cool tissue. It has the ability to produce force and absorb force by physically changing its length. When you apply load to your muscle, your muscle has to absorb that load. As it absorbs, the muscle lengthens (eccentrically stretches). If the load is too large or too sudden, the cells inside your muscle tear. So, the more cells that tear, the greater the severity of your muscle strain.

There are two ways load is forced on a muscle: active and passive. What is a passive load? Think about when you perform a stretch. As you stretch the muscle you impose a force that is absorbed by the muscle as it elongates. If the load is too big or too sudden, your muscles will be stretched beyond their recoverable limit (back to its resting state).

Load can also be applied to your muscles actively, either from an outside force or from its own contractions. Think about when you run down the court on a break away in your basketball game. As you sprint at full speed your muscles must contract and produce high forces very rapidly and if you force the muscle to contract too strongly or rapidly, the resulting stretch of the muscle will be too great.

Like most injuries, some muscle strains are worse than others. Your muscle belly itself is composed of many smaller muscle cells. As the load applied to the muscle exceeds your muscle’s capacity to absorb that load, these smaller cells are stretched beyond their limits. The result? They tear—and the more cells that are torn, the greater the severity of the strain.

When the majority of cells in a muscle reach beyond their stretch limit, a complete muscle tear occurs. Not all cells in your muscles are created equal. Some muscles are more prone to strain than others. This is because muscle strains occur where your muscle cells transition into their tendon (the tissue that connects muscle to bone). This transitional region is prone to strains because the tissue in this area is neither quite as strong as the muscle belly or the tendon.2, 3 It’s a literal “weak link.”

Because most tears occur in the weaker transitional areas of muscle, we see more strains in muscles that have two joints (or two tendon connections to bones). This occurs in areas like your hamstrings (at your knee and hip) or your biceps (at your elbow or shoulder).

How You Can Recover Faster

Like the majority of your body tissues, muscle has the capacity to heal itself. But before you can get back to your game after a muscle strain, you need to understand how a muscle heals—and what that means for your recovery.

Your muscles will heal after a tear, but not through growing new muscle. Instead, your body uses what we call “foreign” tissue (or scar tissue) to patch in the damage. This foreign tissue is weaker and less elastic than the muscle tissue itself. Unfortunately, this means that the transitional area of your muscle just got a bit weaker. This is why muscles that were previously strained have a higher chance of re-injury.

If the strain is minor, your muscle will repair within three to six weeks. Fortunately with these injuries, if the muscles surrounding the scar tissue hypertrophies (or grows through strength training), your muscles will have no real loss of function/strength. For more severe tears, the reparation process can take several months.

Keep in mind that the dense scar tissue that results can impair future muscle function and contribute to future pain. What does that mean for recovery? The secret to getting back in the game after a muscle strain is to keep your injury site at rest while still keeping your body active. Like all injuries, allowing the angry tissues to calm down is key—this means staying away from activity that aggravates the area.

However, this does not mean that you should stop all activity. Athletes who completely rest after experiencing injuries like muscle tears actually increase their chances for re-injury. If you rest completely, your body will decondition.

This decrease in fitness means:

- You will have a slower recovery time.

- Your injured area will have decreased strength and capacity to handle loads in the future.

This is why athletes who train around their injury or “relatively rest” can improve recovery. Maintenance of conditioning with different modalities that do not aggravate the injured area has a crossover effect. Working the non-injured limb decreases the time it takes for the injured limb to essentially “catch up.” If you are suffering from a muscle strain, make sure you let your tissues heal while working your other ones to stay strong.

What About Stretching?

Let’s put our thinking hats on. If a muscle strain is just a bunch of small muscle fiber tears caused by too much load and too much stretch then if we stretch after a strain we will only add to the problem! In the acute phase of the tear, you need to let the tissues relax. This means that you have to leave them alone.

Work around the injury to ensure you maintain good blood circulation so that your body can do its thing. As the injury starts to heal and pain is reduced, we do want to regain our range of motion (ROM) at the site of injury. This is where a lot of old school methodologies like static stretching could play a part, but as we discussed in our previous article, improving a joint’s ROM will not reduce your chance of injury without gaining strength within that range of motion.

I’d like to be clear, static stretching will not make you stronger. Without strengthening an improved range of motion, better positions alone will not be enough to reduce your chance of injury.4

Luckily, as the authors of Strength and Conditioning for the Female Athlete explain, “every strength session an athlete does is a flexibility-strength workout.” This means through lifting, an athlete will not only return to her original baseline strength but become even stronger than she was before.

So, when can you stretch? Think of stretching as something that may help you reduce the sensation of pain. If you’re feeling tight, go ahead and do some stretches or foam rolling after your workout.

Here’s how to combat the three things that influence your chances of getting a muscle strain.

1. Little to No Warm Up

You have to make time to warm up. So what’s the recipe for a good warm up?

- Use lower intensity movements (aerobic) that aim to gradually elevate your heart rate.

- Practice of movement patterns to progress into full play.

- Think hamstring sweeps, inchworms, to high knees, to sprints.

- Think split squats, to bodyweight squats, to goblet squats, to back squats.

Body Weight Split Squat from Restless Athletics.

The goal of the warm-up is to not only prepare the body physically for movement but also mentally. When you practice the movements you wish to perform later at higher intensities, you improve your motor control.

2. Inadequate Strength and Mobility

Strains occur when your muscle reaches its threshold for a load. By improving your body’s capacity to handle higher loads, the better chance you have at avoiding a hammy strain next season.

Research has consistently demonstrated the positive relationship between athletes engaged in a properly executed strength training program and reduced injury risks. At the end of the day, we know injuries occur when the stress applied is too high. If we want our bodies to be able to handle these high stresses, we must prepare them better.

Strength training acts as a tool to reduce your injury risk simply because it improves your tissues ability to handle high loads.6 When performed with an attention to movement quality, the athlete improves her motor control leading to both improved performance and decreased injury risk. What we are saying is that the athlete with a higher work capacity can handle higher loads, do more work, recover better from that work, improve at a faster rate, and can reduce the chance of being sidelined.

3. Excessive Fatigue

So, I think we understand by now that strains occur when loads are too fast or too big. But what does fatigue have to do with it?

When muscles are continually loaded (like in a three-hour volleyball practice or all day tournament with insufficient recovery), they fatigue. When your muscles are fatigued, their elastic qualities, as well as those of your tendons, decrease. This means there is less wiggle room for your muscles to stretch. Less wiggle room equates to a higher likelihood they will tear.

When your central nervous system is fatigued (think that drained feeling), there is greater likelihood your movement patterns deteriorate. In addition, poor mechanics can contribute to improper muscle loading, also increasing the likelihood of strain.

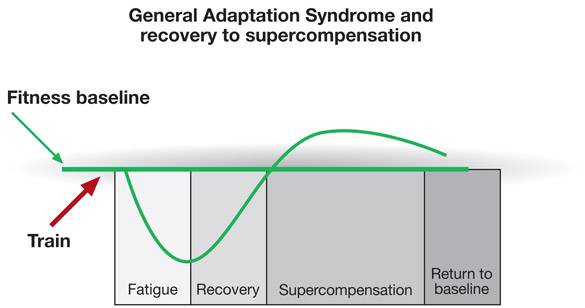

So, how can you avoid fatigue? Fatigue is a necessary factor in making physical improvements. Your body fatigues as a result of being broken down, and your body cannot build back up for the better without first being broken down. Your muscles will always fatigue with increased volume of play: training, practice, or games. We can reduce this type of fatigue through recovery methods like ice baths and foam rolling. However, your body will naturally recover (and adapt) from fatigue with sufficient sleep and nutrition.

Nervous system fatigue is another necessary player in the improvement game. If you want to learn a new skill, you have to stress the system. Unfortunately, this type of stress is also felt through other aspects of our life—think school/work, social components, and other emotional factors that influence how you feel. We can reduce this type of stress through methods in addition to sleep and nutrition such as relaxation, massage, meditation, and even laughter.

Watch Over Your Muscles

If you load your muscles by stretching too hard or too fast by performing sudden intense movements, they can tear. The severity of this tear depends on the amount of load applied and the time your muscle experiences the load. With enough rest for tissue recovery, plus strength training for improved work capacity and strength, you could be back in action in just a couple of weeks. But beware—completely resting or jumping back in the game too soon could put you out for the season.

Strength training is key. You can improve your ability to handle these high loads by hitting the weight room. Remember, a stronger female athlete is more resilient to any force that comes her way.

References:

1. Heiderscheit, B. C., Sherry, M. A., Silder, A., Chumanov, E. S., & Thelen, D. G. (2010). Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2), 67–81.

2. Whiting W, Zernicke R. Biomechanics of Musculoskeletal Injury. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2008.

3. Tidball J, Salem G, Zernicke R. Site and Mechanical Conditions for Failure of Skeletal Muscle in Experimental Strain Injuries. J Appl Physiol 1993;74:1280–6.

4. Anderson, J. C. “Stretching Before and After Exercise: Effect on Muscle Soreness and Injury Risk“. Journal of Athletic Training 40.3 (2005): 218–220. Print.

5. Sargent, D., Clarke, R. (2018). Strength and Conditioning for Female Athletes. Mobility for Performance in Female Athletes. Marlborough: Crowood. pp 111-139.

6. Malone, Shane, Hughes, Brian, Doran, Dominic A., Collins, Kieran, Gabbett. Tim J. Can the workload–injury relationship be moderated by improved strength, speed and repeated-sprint qualities? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport.