Your core is a complex series of muscles, extending far beyond your abs, including everything besides your arms and legs. It is incorporated in almost every movement of the human body.

These muscles can act as an isometric or dynamic stabilizer for movement, transfer force from one extremity to another, or initiate movement itself. The following screens will allow you to assess your core stability and conduct core strength tests to see how you measure up.

Your core is a complex series of muscles, extending far beyond your abs, including everything besides your arms and legs. It is incorporated in almost every movement of the human body.

These muscles can act as an isometric or dynamic stabilizer for movement, transfer force from one extremity to another, or initiate movement itself. The following screens will allow you to assess your core stability and conduct core strength tests to see how you measure up.

What the Core Is

In this article, we address how to become a functional and strong human, as opposed to being another of the overrated endless rants on chiseled abs. So, we must first identify the core and what it looks like. In this diagram, we see the external musculature of the human body.

Our core has three-dimensional depth and functional movement in all three planes of motion. Many of the muscles are hidden beneath the exterior musculature people typically train. The deeper muscles include the transverse abdominals, multifidus, diaphragm, pelvic floor, and many other deeper muscles.

What the Core Does

Your core most often acts as a stabilizer and force transfer center rather than a prime mover. Yet consistently people focus on training their core as a prime mover and in isolation. This would be doing crunches or back extensions versus functional movements like deadlifts, overhead squats, and pushups, among many other functional closed chain exercises.1

By training that way, not only are you missing out on a major function of the core, but also better strength gains, more efficient movement, and longevity of health.

We must look at core strength as the ability to produce force with respect to core stability, which is the ability to control the force we produce.

According to Andy Waldhem in his Assessment of Core Stability: Developing Practical Models, there are “five different components of core stability: strength, endurance, flexibility, motor control, and function”.2

Without motor control and function, the other three components are useless, like a fish flopping out of water no matter how strong you are or how much endurance you have.

It is important to first achieve core stability to protect the spine and surrounding musculature from injury in static and then dynamic movements. Second, we want to effectively and efficiently transfer and produce force during dynamic movements while maintaining core stability.

This can include running, performing Olympic lifts, or picking up the gallon of milk far back in the fridge while keeping your back safe. Research has shown that athletes with higher core stability have a lower risk of injury. This is proven perhaps most effectively by the Functional Movement Screen.3

There is a multitude of various tests that measure core stability, but I consistently use and recommend the FMS because of the research results and effectiveness of the corrective strategies.

Trunk Stability Pushup Test

For the purpose of self-evaluation, we will conduct a simple pass/fail version of the screen (this is different than the standard FMS test, but we will use positions that represent a “2” in that system).

First begin in a prone pushup position, with toes tucked under, lying flat on the ground. Your hands should be shoulder-width apart. Men will have the palms of their hands in line with their chin and women in line with their clavicle (collar bone).

In a single motion, perform a pushup while maintaining a completely straight body. For evaluative purposes, you may use a dowel rod or PVC pipe to asses maintaining a solid core and straight body, as shown below.

Women’s start position, hands in line with shoulders (men start by chin).

Top of pushup.

Passing:

- Proper start position is assumed and maintained (hands may not slide down lower)

- The chest and stomach leave the ground at the same time

- Spinal alignment is maintained with the body moving as a single unit (can use dowel to help determine and measure alignment)

If any of the criteria are failed the screen is deemed as a failing score. You have a maximum of three attempts to complete this screen. If you successfully pass the stability screen, progress to the strength screens.

Progress in core stability and strength should yield more effective progress and strength gains in other movements including both the squat and deadlift. Without core stability gross movement patterns become very difficult to impossible.

Core Strength Tests

The plank and side plank evaluate static core strength, while the knees to chest and toes to bar evaluate dynamic core strength. Finally the deadlift strength evaluation puts a higher demand on the posterior core stability to handle larger loads.

Plank

Hold a plank on your elbows for 90 seconds. Strict posture must be maintained, with a flat back and level hips. A dowel may be used to help evaluate postural alignment. Hands should be in front of shoulders, with forearms parallel to your spine, while elbows are located directly under the shoulders.

If struggling to maintain or find alignment then use the following procedure: Assume the prone position with elbows located under your shoulders. Flex your quads, raising your knees off the floor, squeeze your butt, and tighten and retract your abs. When all three muscles are contracted properly you will lock your hips into the correct position ensuring a flat lower back.

Side Plank

Hold a side plank for 60 seconds. Your elbow must be located directly under the shoulder and feet stacked on top of each other, while maintaining straight spinal alignment horizontally and vertically.

Knees to Chest or Toes to Bar

Complete 5 strict knees to chest for a passing score and 5 toes to bar for an optimal score. While hanging from a pull-up bar, first ensure active shoulder alignment, to keep your shoulders safe, as shown below. Slowly and deliberately lift your toes to the bar (or knees to chest) and lower them under control without swinging. Complete five repetitions.

In order to pass this strength test, you must maintain full movement control, not use any momentum to achieve the full range of motion, and remain pain free.

Left photo: Toes to bar. Right photo: Knees to chest.

Left photo: Active shoulders (good). Right photo: Relaxed shoulders (not good).

Deadlift

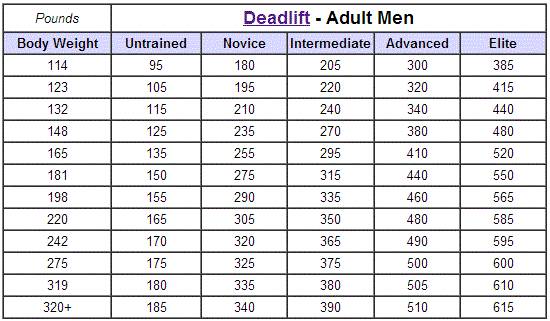

Complete a single deadlift meeting the Novice weight listed below in the strength table. For optimal results complete a single deadlift meeting or exceeding the Intermediate weight. For questions on deadlift form refer to the hip hinge article.

For a detailed core stability, strength, and conditioning program to start improving your screens and working towards optimal strength scores, continue to 10 Day Core Strength Program – Screening, Testing, and Training.

References:

1. “Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises” accessed February 18th 2013

2. “ASSESSMENT OF CORE STABILITY: DEVELOPING PRACTICAL MODELS” Andy Waldhelm May, 2011

3. “Functional Movement Screening” accessed February 18th 2013

4. “Deadlift Strength Standards” accessed February 18th 2013