Diet soda seems an ideal drinking choice when trying to lose weight. It tastes almost as good as regular soda, but contains zero calories. But doesn’t that sound too good to be true? Aren’t there any downsides? In this article I explain how the body reacts to sugar and to sweeteners from diet soda. Then I investigate whether diet soda indeed makes losing weight easier, by looking at how it influences hunger and eating behavior. Soon, you’ll know whether you can enjoy that can of diet pop during weight loss, or whether you’re better off leaving it in the fridge.

One disclaimer before we begin: This article is not about the overall health effects of diet soda. That’s another subject, which I may cover in a future article.

When overweight people drink diet soda they react differently to the next meal. [Photo credit: Urban Fizz]

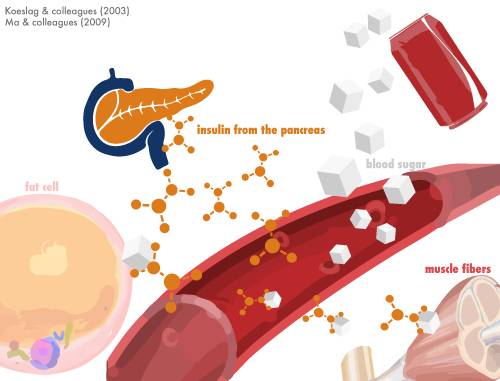

The Body’s Reaction to Sugar

A lot of people think the body deals with low-calorie sweeteners such as aspartame and sucralose (Splenda) in the same way as sugar. To investigate whether this is true or not, we’re first going to look at how the body reacts to sugar from regular soda. When your body detects sugar in the bloodstream, your pancreas produces a certain amount of the hormone insulin.1, 13 The insulin gets into your bloodstream, where it decreases the blood sugar to basal levels by storing a big part of it into fat and muscle cells.

Does the same thing happen when your body detects sweeteners in the blood stream, or does it react differently? Let’s see what the scientific literature can tell us about this.

Note: All studies funded by organizations that produce or sell sweeteners were not included for reference in this article. As these organizations have an interest in certain study results, which is called ‘funding bias,’ I regard them as untrustworthy.

The Body’s Reaction to Artificial Sweeteners

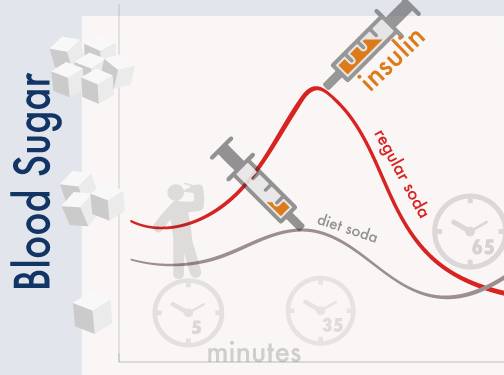

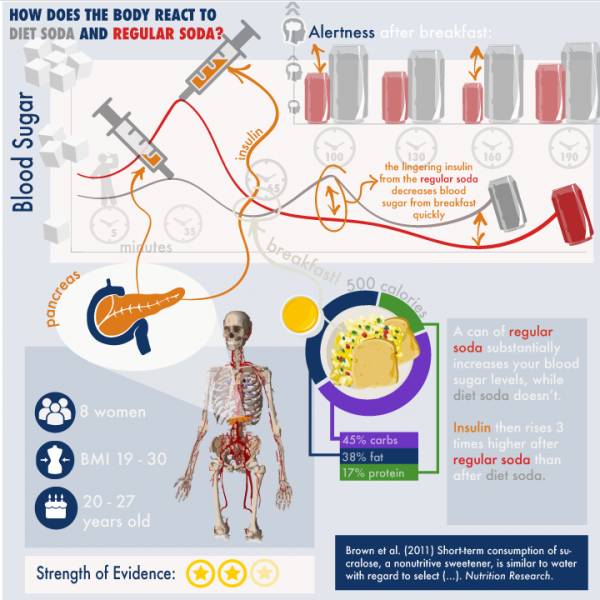

When you drink diet soda, something else happens in your body than when you drink regular soda: your blood sugar level stays low (grey line in the graph below).2 This is logical, because diet soda simply doesn’t contain any sugar. Because insulin’s main purpose is lowering your blood sugar level, the body also doesn’t react by pumping a lot of it into the bloodstream. Therefore, there’s also only a minor rise in blood insulin levels.2, 3, 10, 13

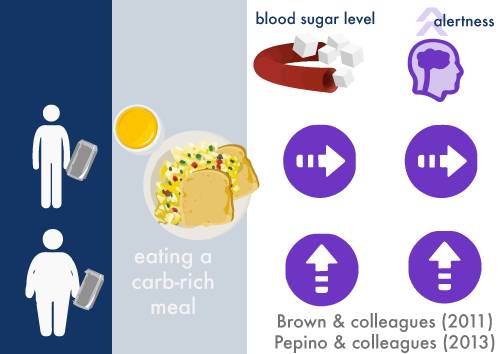

However, multiple studies do show that drinking diet soda has a surprising after effect for those that are overweight (BMI > 25).2, 9 When overweight participants ate a carbohydrate-rich meal 10 to 60 minutes after drinking the diet soda, their blood sugar level increased. A lot. Much more than the meal did after drinking water or regular soda (the other study conditions). The grey line in the graph below, which is based on one of these studies, illustrates this.2

Furthermore, the overweight diet soda participants also felt more alert after the meal. The bar graph in the top-right corner of the image below shows this. Now you might think “sure, but this is just a post-meal sugar rush.” Well, not really; hours after finishing the meal, these blood sugar and alertness effects were still present.2

Artificial Sweeteners and Insulin Timing

Why did the overweight participants react this way to the meal after drinking diet soda?

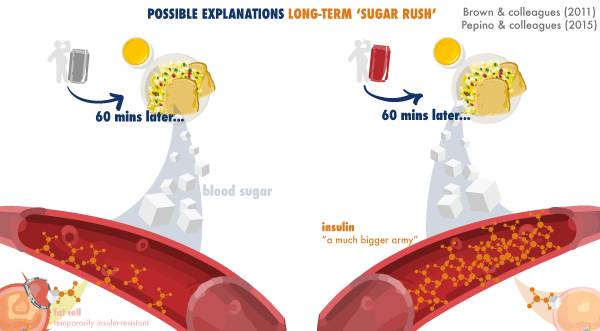

There are at least two possible explanations for why the overweight participants had a long-term increase in blood sugar and alertness. First, researchers propose that sweeteners in diet soda may somehow temporarily make overweight people insulin resistant (basically that’s like having short-term diabetes).3 One study which showed the participants needed 20% more insulin to bring their blood sugar down to normal levels.9

Second, the participants who had drunk regular soda (instead of diet soda) still had lingering insulin in their blood, up to four times as much as the diet soda participants.2 In other words, they had a much bigger ‘army’ of insulin soldiers, ready to take on any blood sugar that would be absorbed after eating the meal. That means less time to get the blood sugar molecules into the fat and muscle cells. After drinking diet soda, the same process takes much longer, because the army of insulin soldiers was up to four times smaller. So the blood sugar stayed elevated for longer, which may also explain the increased alertness.

In short, when overweight people drink diet soda they react differently to the next meal: their blood sugar level and alertness increase.2, 9 These effects last for hours, and researchers think it may have something to do with temporary insulin resistance, or the lack of insulin in the blood when eating the meal (compared to after drinking regular soda).2, 3, 9 The research doesn’t show these effects of diet soda for lean people. But overweight people (BMI > 25) should be aware of this phenomenon, and schedule their diet soda consumption accordingly.

Diet Soda and Hunger

Several studies show drinking diet soda only temporarily relieves hunger, making you hungrier after about 30-60 minutes.4, 11, 12 However, this only happens when you drink the diet soda by itself (without food). Having a diet soda along with your meal is perfectly fine, and doesn’t seem to increase hunger at all. The delayed increase in hunger after drinking diet soda by itself is possibly because you taste something sweet, without consuming calories. However, researchers remain in debate about this.4

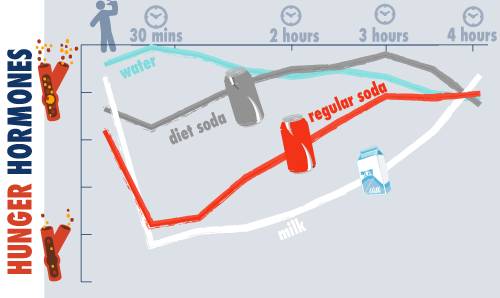

The body’s ‘hunger hormones’ (ghrelin, GLP-1, and GIP) may also have something to do with it. One study investigated the effects of regular soda, diet soda, semi-skimmed milk, and water on these hunger hormones.5 You can see the results in the graph below. Every line represents the mean of the related hormones.

As expected, regular soda and milk (red and white lines) decreased the amount of hunger hormones in the blood, because they have calories. Diet soda (grey line) however had a smaller effect, and even caused the hunger hormones to get higher than after drinking water (blue line) at the three-hour point.

So drinking diet soda by itself doesn’t seem to be a great idea when your next meal is still some hours away, because of the increase in hunger after 30-60 minutes. Researchers think this may have something to do with tasting something sweet, without consuming any calories. They have also found an increase in hunger hormones 1-3 hours after drinking diet soda, which are related to feeling hungry.4, 5

Diet Soda and Compensation Eating

Drinking diet soda by itself will cause you to be hungrier sometime after. But does this increased hunger then make you eat more? Do you compensate for the lack of calories in the diet soda by eating more calories during the following meal? Intuitively, this sounds likely. However, multiple studies show that it’s not true.5, 7, 8

The participants from the previously discussed study on the effect of regular soda, diet soda, milk, or water on hunger hormones found that the participants ate the same amount of pizza slices four hours after they had the drinks.5

Basically, research shows that drinking diet soda in the afternoon likely increases hunger after an hour or so, but it probably doesn’t increase how much food you eat at dinner.

Diet Soda for Weight Loss?

Multiple studies found that overweight people react differently to diet soda than people with a healthy weight.

For overweight people, drinking diet soda 10 to 60 minutes before having a meal will possibly ‘enhance’ that meal’s blood sugar and alertness effects, compared to drinking regular soda. Whether you see that as a positive or a negative is up to you. However, whether you have a healthy weight or you’re carrying around some extra pounds, drinking diet soda can be useful for the following reasons:

- It makes the drinking part of your diet less restrictive, and lets you enjoy something sweet, without getting in extra calories. This can give you a mental boost to adhere to your diet long-term.

- Drinking diet soda is a great way to decrease hunger in the short term (for about 30 minutes). However, be aware that you’ll probably get hungrier 1-3 hours after drinking that can of diet soda than if you would have had some water.

- You probably won’t overeat on your following meal to compensate for the lack of calories in the diet soda.

- Drinking diet soda during a meal has no negative metabolic consequences, so it’s an easy way to strip off 100-150 calories during lunch or dinner.

Get your mind right:

The Disconnected Values Model of Motivation

Learn how to coach any client:

The 3 Levels of Athlete Ability (and How to Coach Them)

References:

1. Koeslag JH, Saunders PT, Terblanche E (June 2003). A reappraisal of the blood glucose homeostat which comprehensively explains the type 2 diabetes mellitus-syndrome X complex. The Journal of Physiology (2003) 549 (Pt 2): 333–46.

2. Brown, A. W., Bohan Brown, M. M., Onken, K. L., & Beitz, D. C. (2011). Short-term consumption of sucralose, a nonnutritive sweetener, is similar to water with regard to select markers of hunger signaling and short-term glucose homeostasis in women. Nutrition Research, 31(12), 882–888.

3. Pepino, M. Y. (2015). Metabolic effects of non-nutritive sweeteners. Physiology & Behavior, 152, 450-455.

4. Mattes, R. D., & Popkin, B. M. (2009). Nonnutritive sweetener consumption in humans: Effects on appetite and food intake and their putative mechanisms. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(1), 1–14.

5. Maersk, M., Belza, A., Holst, J. J., Fenger-Gron, M., Pedersen, S. B., Astrup, A., & Richelsen, B. (2012). Satiety scores and satiety hormone response after sucrose-sweetened soft drink compared with isocaloric semi-skimmed milk and with non-caloric soft drink: a controlled trial. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(4), 523–529.

6. Pasquali, R., & Vicennati, V. (2001). Obesity and hormonal abnormalities. International Textbook of Obesity. Wiley & Sons: Chicester, UK, 225-239.

7. Flood, J. E., Roe, L. S., & Rolls, B. J. (2006). The Effect of Increased Beverage Portion Size on Energy Intake at a Meal. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 106(12), 1984–1990.

8. Soenen, S., & Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2007). No differences in satiety or energy intake after high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, or milk preloads. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 86(6), 1586-1594.

9. Pepino, M., Tiemann, C., Patterson, B., Wice, B., & Klein, S. (2013). Sucralose affects glycemic and hormonal responses to an oral glucose load. Diabetes Care, 36(September 2013), 2530–2535.

10. Renwick, A. G. (1994). Intense sweeteners, food intake, and the weight of a body of evidence. Physiology & Behavior, 55(1), 139-143.

11. Black, R. M., Leiter, L. A., & Anderson, G. H. (1993). Consuming aspartame with and without taste: differential effects on appetite and food intake of young adult males. Physiology & Behavior, 53(3), 459-466.

12. Tordoff, M. G., & Alleva, A. M. (1990). Oral stimulation with aspartame increases hunger. Physiology & Behavior, 47(3), 555-559.

13. Ma, J., Bellon, M., Wishart, J. M., Young, R., Blackshaw, L. A., Jones, K. L., … Rayner, C. K. (2009). Effect of the artificial sweetener, sucralose, on gastric emptying and incretin hormone release in healthy subjects. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 296(4), G735-9.