Today we speak of the standard weightlifting, powerlifting and strength exercises. But how “standard” are they? How did they get to be standard?

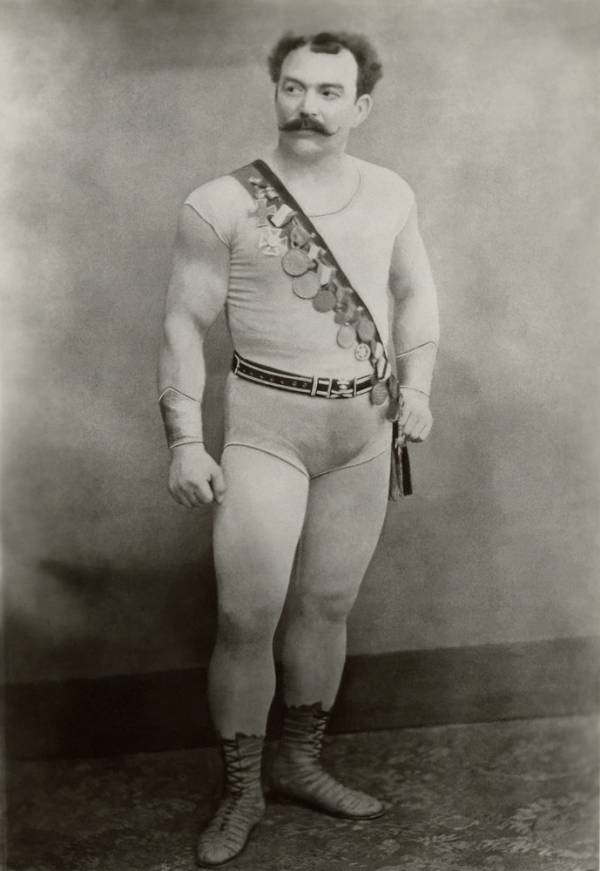

In the beginning there was the age of the professional strongman, performing on the vaudeville and music hall stages of Europe and America in the late 1800s. Professional events were flamboyant displays of strength and purposely non-standardized. Every performer wanted to bill himself as “The Strongest Man in the World.” Since no one was interested in seeing the second strongest man in the world a few gambits had to be resorted to if everyone was to eat (and that was then, as now, a favorite activity of lifters). Some used trickery to get their edge. Hollow barbells with flowing mercury would beat many who tried to duplicate their master’s feat.

Others were more honest ones but also more imaginative. To ensure that all could establish some claim to the mythical title “World’s Strongest Man” they specialized. Each would take a certain pet lift and become very good at it. Out of professional courtesy and also to protect their own egos and reputations these lifts would be avoided by their competitors. Then they could all claim that they were at least the strongest man in the world at that particular lift. This situation prevailed up until the start of World War I.

At the same time as professional lifting was unknowingly on its last legs, amateur weightlifting was beginning to develop. Quite unlike the pros there was a need for standardization that would allow some comparison among the performers now taking up the activity. This standardization process was not smooth or straight forward. Each national culture specialized in its own verity of strength testing, many of which had been folk activities for a long time, perhaps centuries.

The Russians lifted kettlebell-type weights for repetitions. The Scottish liked to throw heavy implements. The Basques hefted their stones shoulder high. The Germans and Austrians used heavy globe barbells lifted overhead in awkward movements. The French preferred more aesthetic lifts that did not touch the body. Some liked single-lift tests of maximum strength, others multi-repetition endurance lifting, some others liked to include balance feats along with strength displays. Both one- and two-hand lifting saw popularity in different countries.

The Russians lifted kettlebell-type weights for repetitions. The Scottish liked to throw heavy implements. The Basques hefted their stones shoulder high. The Germans and Austrians used heavy globe barbells lifted overhead in awkward movements. The French preferred more aesthetic lifts that did not touch the body. Some liked single-lift tests of maximum strength, others multi-repetition endurance lifting, some others liked to include balance feats along with strength displays. Both one- and two-hand lifting saw popularity in different countries.

One contest in 1878 featured twenty lifts, including lifting with fingers, squats, one- and two-hand jerks, swings, presses, endurance presses, bench presses and lastly, press, snatch, and clean and jerk. Many devotees believed that a champion should be able to do everything. But such contests were unwieldy. Something had to be done, but each lift still had its proponents. It took a long time to decide just what performance principle would prevail.

Weightlifting in the inaugural 1896 Olympics in Athens featured two events, a one-handed lift and a two-handed lift. There were no bodyweight categories so size would be an asset under these conditions. This regime did not last. As world or European championships began to be organized by individual countries the lifts contested could change with the venue. The Germanic nations liked overhead lifts while Britain, France, America and Russia favored one-arm lifts requiring balance. In some competitions performances were not measured in pounds or kilos but were based on some point system. Technical errors would result in deducted points or weight if so measured. A major step forward was the introduction of bodyweight categories by the British, influenced by what was already done in boxing. The Germans had also proposed a set of three height classes but this did not take hold.

In 1901 Marquis Luigi Monticelli-Obizzi of Italy made a list of suggestions that would result in significant changes over the course of time, if not immediately. Among these was the elimination of exercises performed in only one country. International popularity would thus count for something. Lying exercises would be eliminated as well as this requiring side or forward raised arms. There would thus be fewer lifts and these would involve the large muscle groups, not specialized single joint movements. Duplication of exercises was also to be avoided. Therefore right and left one-arm versions of the two-handed lifts could be eliminated as well as those using two-hand lifts with separate weights in each hand. Twisting movements were also dropped since they were due more to flexibility than strength. Endurance lifting would also be dropped because it was not a good gauge of power and also harmful if done to extremes. This genre would go into hibernation for a century, awaiting the development of CrossFit.

What remained were mostly the three classic Olympic lifts. They did not become standard until the 1928 Olympics, although they were used with one-arm lifts in the earlier 1920s. This remained the competition set until 1972 when the press was dropped. The press started as a strict military press but developed over the years into a quick lift, all done very loosely. Here is a video of Doug Hepburn at the 1954 Commonwealth Games:

The French-inspired “clean” style of bringing the bar to the chest was finalized in the years after World War I. And that clean was a split version. Cleaning replaced the awkward “continental” style favored by the Germanic nations as that war’s winners could prevail in its aftermath. The Germans then developed the squat style as a replacement method of raising the bar. American coach Larry Barnholth greatly improved the squat style’s technique, which was later perfected and used almost exclusively by all lifters.

The power lifts were not competed on much until the 1950s, being referred to as “odd lifts” in those days. The deadlift was the oldest, having been a pet lift of professional Herman Goerner of South Africa in the 1920s. It was used as an assistance exercise in the intervening years before Bob Peeples of the United States matched Goerner’s level in the 1950s.

Squatting was first popularized by Italy’s Marquis Alfred Pallavicini and then more famously performed by pro strongman-wrestlers Milo Steinborn and Bert Assirati in the 1930s and 1940s. After Steinborn the weight world would have to wait for the arrival of Canada’s Doug Hepburn and the U.S.A’s Paul Anderson in the 1950s before 600 pound squats were again performed. Here Paul Anderson performs a 435 pound clean and press:

The bench press was a little known exercise until the late 1940s. It was probably helped a bit by its use in rehabbing soldiers injured in World War II. Again it took off in the 1950s with superb performances by Hepburn and Marvin Eder. In the 1960s powerlifting would emerge as a new sport and would then diverge from Olympic lifting and develop separately. Curls and upright rows had been contested in some early meets but these were dropped in the early 1960s.

It is important to know our iron sports history and how we have come to the exercises used in most gyms throughout the world. When we do it becomes apparent that the lifts we have now were not inevitable but were the result of consultation and compromise by the founders of our sports over a period of years. With different personalities and different history, who knows, we might all be doing totally different “standard” lifts today.

References:

With thanks to Gottfried Schödl’s The Lost Past, 1992, an IWF publication.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.