In the sport of weightlifting, the key requirement of a successful lift in competition is to lift the barbell to the full extent of the arms, while under control. As such, the elbows and their associated ligaments and tendons have to be healthy if you intend to consistently get three white lights from the referees.

In the sport of weightlifting, the key requirement of a successful lift in competition is to lift the barbell to the full extent of the arms, while under control. As such, the elbows and their associated ligaments and tendons have to be healthy if you intend to consistently get three white lights from the referees.

While this is important for both the snatch and the jerk, it is in the latter lift where problems occur most often. This is due to the fact that jerk weights are about 25% heavier. It is a shame to see a lifter pull a huge weight and then at the moment of it going overhead have the bar stopped before getting to arm’s length. And contrary to popular opinion the referees do not like giving red lights for this, but that is their job.

This condition is popularly referred to as “having bad elbows” but is more scientifically labeled as incomplete shoulder articulation. In weightlifting competition, this will lead to both incomplete lockouts and re-bend problems. Re-bends occur when the bar does go to full elbow extension, but then the elbows do not maintain that position and re-bend slightly so the lifter has to press out the bar to get back to full extension. More red lights.

This problem seldom affects younger lifters other than those with previous elbow injuries. Among older lifters, there are two groups that most often seem to have this problem.

1. Athletes Who Began in Bodybuilding

In bodybuilding-style training, athletes strive to keep their muscles under tension as much as possible in order to increase hypertrophy. Locking the joints takes the tension off, so they try to avoid this. This is fine in bodybuilding, but not in strength training. Training extensively this way over a number of years will eventually result in elbows that have difficulty locking out.

“You see many bodybuilders bench pressing a bar only about three quarters of the way and then returning to do the next rep. This is not how any lifters should train.”

The biggest cause of future jerking problems is probably arm curls. Bodybuilders do a lot of arm curls so many of them eventually have troubles locking out. This won’t bother them as bodybuilders, but those who try to convert to weightlifting or powerlifting are going to have problems.

I remember one Olympic weightlifter who had apparently done many curls along with his regular training lifts. In doing so, he had developed a huge set of biceps. He arm pulled an easy 170kg snatch at the Olympics and was in position to medal. Instead, he missed all three jerks because he could not hold 200kg overhead despite having made easy cleans. His lockout was sufficient to hold the lighter snatches but not his jerks. Arm pulling is not how you should pull in weightlifting, but his arms were so strong that he could succeed even with that flaw. But it was his undoing when it came to the basic task of totaling.

2. Athletes With Tendon or Ligament Injuries

With proper therapy, these injuries can sometimes be overcome, at least for a time. But what often happens is that these injuries reassert themselves as the lifter ages, and the lifter unconsciously avoids locking out fully.

“The back injuries didn’t stop him, but the elbow ones eventually did. He just could not hold jerks anymore.”

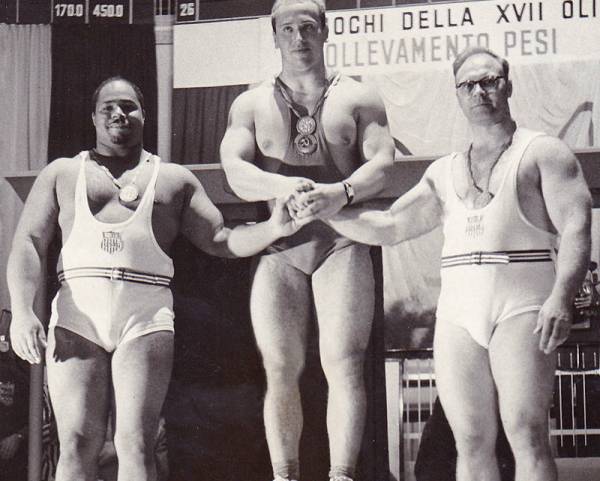

A good example was the great Norbert Schemansky of the United States. In his younger years, he could jerk anything that wasn’t nailed down, though his press was relatively weak. In his late thirties, while still an elite competitor, he gained some bodyweight, which really helped his press. But he had also gone through a number of elbow injuries, not to mention two spinal fusions. The back injuries didn’t stop him, but the elbow ones eventually did. He just could not hold jerks anymore. In fact, in one of his final contests, he pressed more than he jerked.

Normal Schemansky (far right) at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Italy.

How to Avoid Problems

The best way to avoid lockout problems is to start your training with a good lockout and to keep it that way. Don’t get lazy and cut your lifts short, especially your presses and jerks. You see many bodybuilders bench pressing a bar only about three-quarters of the way and then returning to do the next rep. This is not how any lifters should train.

“Weight training movements, whether in bodybuilding or weightlifting, do not usually involve such a sudden stop at the finish so full lockout is not problematic.”

This is related to the specific adaptation to implied demand (SAID) principle basic to all training. If you never train straight-arm strength, then the position is never going to be as strong. The connective tissue will not be able to bear the load. The muscles and surrounding infrastructure get used to working in a shortened range of motion. The proprioceptive receptors than do not allow the joints to straighten, especially under load.

The “never lock your arms” advocates often use a disingenuous analogy to support their claims. They use the example of jumping upward and then landing on bent knees. They point out how ridiculous it would be to land on the straight knees. The bending does amortize the force of landing—but in the gym, you do not have those forces. Weight training movements, whether in bodybuilding or weightlifting, do not usually involve such a sudden stop at the finish so full lockout is not problematic.

What to Do if You Have a Lockout Problem

Your solution this depends on how long you have been living with the condition. Those who are younger and have not had lockout problems all their lives will have an easier time than those with a long history of the problem. The former can work to improve their lockouts. The latter may have to live with the condition and train around it.

“Many masters-age lifters may not ever obtain a decent lockout. Despite that, they can still do limited range training to strengthen the top of the lift.”

If you think your lockout is salvageable, you might want to try limited range training. The goal of this training is to press the bar out the last few inches prior to lockout and then at the top of the range of motion hold the barbell for a certain amount of time. (This can be done in the overhead position or in a bench press position.) The weight has to be heavy enough that you have to fight with it, so you are looking at near-limit poundages. This will not feel natural at first, but persevere until it does.

You will need to do your limited ranges inside a power rack, not only for safety but also to get a measured amount of movement in your lockout. Train your lockout this way once or twice a week striving to increase the holding time at the top. When you can hold the weight for five to seven seconds, then you can increase the weight for your next workout. You may not be able to hold it as long in your first workout with the new poundage. Don’t get discouraged, as you will be able to hold it longer in your second and third sessions. Keep going like this until you can easily handle your maximum clean.

Do What You Can

Many masters-age lifters may not ever obtain a decent lockout. Despite that, they can still do limited range training to strengthen the top of the lift. This is not a perfect solution, of course, but at least it gives you some finishing strength that might mean you hold the bar long enough to get those white lights. Just don’t forget to let the referees know you have lockout problems.

In short, if you can’t straighten the arms you can at least strengthen them. Straightening the arms and holding isometric positions for progressively longer durations and more challenging leverages can both straighten and strengthen your elbow joints to levels that will surprise you.

More Like This: