What is a clean and snatch complex? Essentially, it’s the breakdown of these Olympic lifting movements into individual lifts. It is broken down in order to properly build each section of the complete lift. Each person’s complex may look a little different. My personal complex is very broken down. Others may be more efficient or further along in their learning and therefore may have fewer pieces broken down.

If you are curious about my complex, here it is as an example:

Clean Complex:

- Deadlift

- Thigh high hang pull

- Hang power clean

- Time-under-tension front squat

Snatch Complex:

- Snatch grip deadlift

- Thigh high hang pull

- Hang power snatch

- Time-under-tension overhead squat

Okay, now that you know what a complex looks like and you may have even realized you’ve done them before, let’s go over some of the neurological benefits of these Olympic lifts and why we do them in complexes. We’re going to look at motor unit recruitment, proprioception, and the central nervous system and how using complexes trains each of these to make us better lifters.

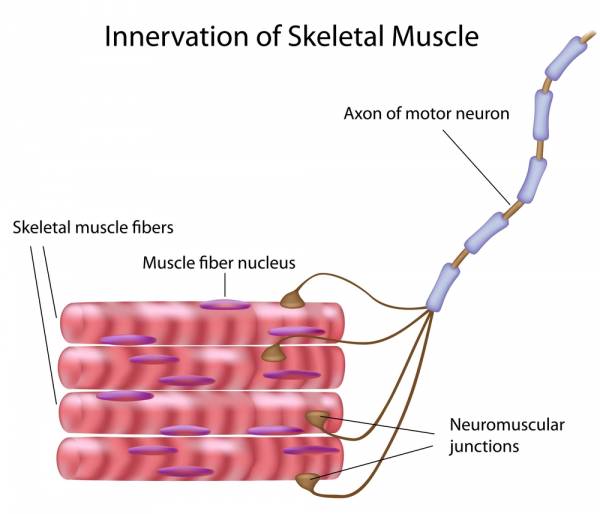

Motor Unit Recruitment Patterns During Lifting

Yes, motor units (or neurons) are part of the neurological system. The ability to vary or graduate force is essential for performance of smooth, coordinated patterns of movement. For this to happen, muscular force can be graded in two ways:

1. Through variation in the frequency at which motor units are activated.

If a motor unit is activated once, the twitch that arises does not produce a great deal of force, but if the frequency of activation is increased so the forces of the twitches begin to overlap or summate the resulting force developed by the motor unit is much greater. The best analogy I can give is Morse code. One click does not do much to show you what the person is trying to say, but increase the frequency of clicks and then you are able to decipher what the person is trying to communicate. This is a similar concept to motor neuron frequency. Force output of whole muscles is intensified through increased frequency of firing of the individual motor units. It should also be noted that this method of modulating force is particularly important in small muscles such as the hand.

2. Through varying the number of motor units activated, or recruited.

In large muscles, motor units are activated at near tetanic (maximum stimulation) frequency when called upon. Further increase in force output is achieved through recruitment of additional motor units. For example, say you are trying to lift a heavy king-sized, Memory Foam bed. You can’t lift it by yourself (maybe you can, but humor me for a second), so you add five other people to help you. With all five of you working together, you are able to lift the bed to its destination. If the activity requires near maximal performance (like a clean or snatch) most motor units are called into play, with fast twitch units making more significant contribution to effort (remember we all have both fast and slow twitch fibers in our bodies in different distribution). It’s important to mention this recruitment pattern takes time and is not 100% achievable in individuals who are untrained.

In large muscles, motor units are activated at near tetanic (maximum stimulation) frequency when called upon. Further increase in force output is achieved through recruitment of additional motor units. For example, say you are trying to lift a heavy king-sized, Memory Foam bed. You can’t lift it by yourself (maybe you can, but humor me for a second), so you add five other people to help you. With all five of you working together, you are able to lift the bed to its destination. If the activity requires near maximal performance (like a clean or snatch) most motor units are called into play, with fast twitch units making more significant contribution to effort (remember we all have both fast and slow twitch fibers in our bodies in different distribution). It’s important to mention this recruitment pattern takes time and is not 100% achievable in individuals who are untrained.

This is where complexes come into play. Breaking down movements can help the athlete adapt to bringing in more motor neurons and building recruitment patterns in muscle tissues.

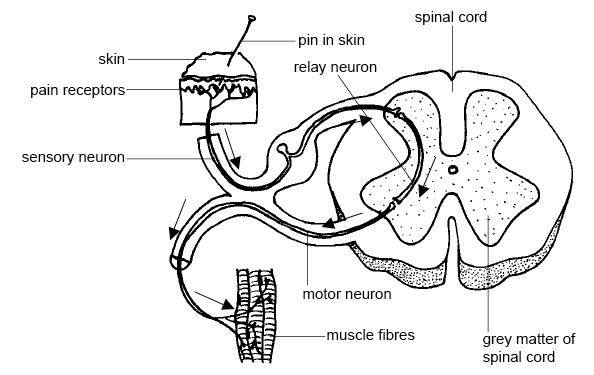

Developing Our Proprioception

Proprioception is important in regards to new athletes and also relates to our beloved complexes. Proprioception involves specialized sensory receptors located within joints, muscles, and tendons. Because these receptors are sensitive to pressure and tension, they relay information concerning muscle dynamics to the conscious and subconscious parts of the central nervous system (CNS). The brain is thus provided with information concerning kinesthetic sense, or the position of the body in relation to gravity. Most proprioceptive information is processed at subconscious levels. Another aspect of proprioception is that it provides the CNS with info needed to maintain muscle tone and perform complex and coordinated movements.

Okay, so let me explain all of that. Let’s take the first part – kinesthetic sense, the position of the body. I will mention the snatch (because it’s my weakest lift). We need to know where we are in relation to the bar when we do a snatch, right? We can’t even see it the whole time! And I need to know when I have to receive the bar for the snatch to be successful. This sense of knowing where your body is in relation to the bar is something that is developed over time. It doesn’t just happen, but complexes can aid in this development.

The second benefit of bolstering our proprioception, coordination, is also something that is learned through practice. Throw someone into an Olympic lift right off the bat and we all know the coordination is not there yet. Doing complexes helps people coordinate the lift. By breaking down the overall movement, a person begins to understand when to perform the specific parts. The three common faults I tend to see in cleans are early pulls, slow elbows, and when to receive. Complexes can aid in all three of these faults, and aid in the proprioceptive aspects of learning the lifts.

The Role of the Central Nervous System

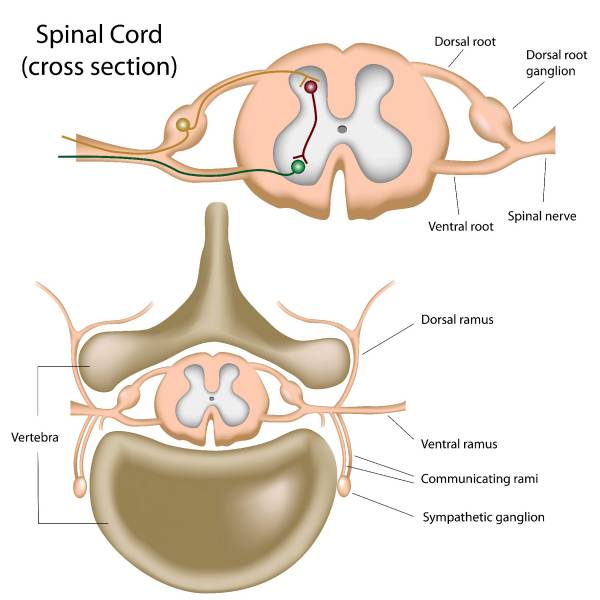

The CNS operates as a type of body control center and complex communication system. It is composed of a sophisticated network operating both chemically and electrically. First we need to understand how transmission works in the CNS. Transmission involves incoming information being transmitted via afferent (incoming) nerve cells to the ventral (underside) of the spinal cord. This information is then sent to the brain. Your brain interprets the information and decides on an action. The brain’s response is sent via efferent (outgoing ) nerve cells back down the dorsal (back) side of the spinal cord to your muscles. This is how you control your body in everyday situations without even really thinking.

The CNS operates as a type of body control center and complex communication system. It is composed of a sophisticated network operating both chemically and electrically. First we need to understand how transmission works in the CNS. Transmission involves incoming information being transmitted via afferent (incoming) nerve cells to the ventral (underside) of the spinal cord. This information is then sent to the brain. Your brain interprets the information and decides on an action. The brain’s response is sent via efferent (outgoing ) nerve cells back down the dorsal (back) side of the spinal cord to your muscles. This is how you control your body in everyday situations without even really thinking.

But when first learning Olympic lifts, we tend to think too much. It’s not like everyday walking. Eventually you do want to get to the point where you lift without thinking, but this takes practice and time. Even then, advanced athletes are constantly tweaking their form and perfecting their lifts. Complexes can help build the lift into your memory so at least the fundamental movement is done without much thought.

Well, without conscious thought, that is. As far as what your brain is up to unbeknownst to you, that’s a different story, so let’s take a quick look at that, too.

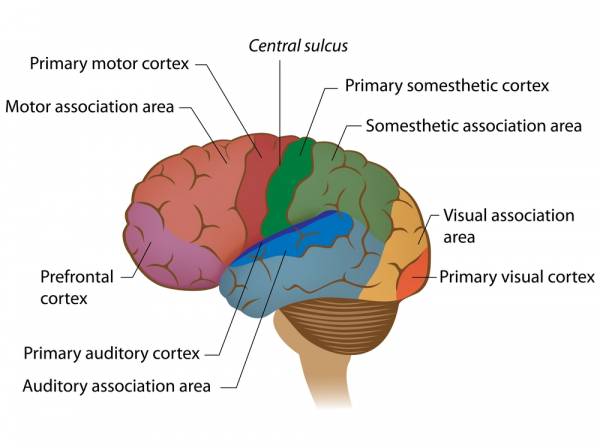

Control of Skeletal Muscles in the Brain

Voluntary movements depend on the lower and upper motor neurons. Lower motor neurons have axons that leave the CNS and extend through peripheral nerves to supply skeletal muscles. Cell location is the anterior horns of the spinal cord grey matter and cranial nerve nuclei of the brain stem. Upper neurons form tracts that directly or indirectly control activities of the lower motor neurons. These cells are located in the cerebrum, brainstem, and cerebellum.

The precentral gyrus, located immediately anterior to the central sulcus, is called the primary motor cortex. The action potentials initiated in this region control many voluntary movements (think all your Olympic lifts). The premotor area is located anterior to the primary motor cortex and is a staging area in which motor functions are organized before they are initiated in the motor cortex. The determination is made in the premotor area as to which muscles contract, in what order, and to what degree.

Whew! Your body is up to a whole lot more every time you try to clean or snatch that bar than you probably even knew. And that’s why I wrote this article – so you can see there is more going on when you lift than what you think (literally). There are neurological benefits to Olympic lifting, but they have to be learned over time. Complexes can help new athletes build kinesthetic sense, and as they get stronger, they can bring in more motor neurons and advance their coordination. In saying this, we all have to start somewhere, which is where specificity loading comes into play. So start with complexes, and then move on to your full Olympic lifting movements.

References:

1. Baechle, Thomas R and Earle, Roger W. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. (Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2008), 95-100

2. Tate, Philip. Seeley’s Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. (New York: McGraw Hill Companies, 2012), 300-342

3. Hatfield, Rudolph C PhD. Guide to the Human Brian. (MA: F+W Media, inc), 94-96

4. Parker, Steve. The Human Body Book. (New York: DK Publishing), 69-98

Photos 1,2,3&5 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 4 by Ruth Lawson Otago Polytechnic [CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.