In the mid-19th Century Britain was the undisputed leader of the industrial world. The Industrial Revolution made it the workshop of the world while it also grew wealthy on its so-called invisible exports like interest and insurance. Up to the 1860s it was supreme, with no other country that could match it. Then things happened. Germany was united and decided this British monopoly must end. Then the USA reached critical mass and started to realize its potential. Then France, Russia and even the Austro-Hungarian Empire started their industrialization. This could end in only one result (besides WWI, that is). And that was that Britain would have to settle for a smaller portion of the world economic pie even if they continued to prosper themselves. One could stay on top when no competition exists but this is difficult when others enter the field. And that is what happened to Britain by the early 20th Century.

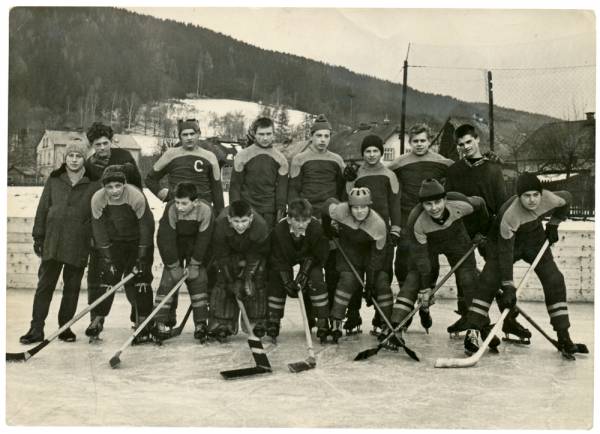

This same phenomenon can be seen in sports. When I was in my school days, the Canadians could always be counted on to win the World Hockey Championships every spring. Unlike today the amateur rules were strict but no matter. Even the Canadian Senior Amateur Champions, plus a few others to bolster the team, could easily win in most years. No other country played hockey in any serious manner. But, that did not last forever. After WWII when some degree of normalcy returned to Europe the Soviets decided they would enter Olympic and world championship hockey. And they planned on winning.

They surprised us when they took the Worlds in 1954. Later the Americans surprised us even more by winning the 1960 Olympics. Both those victories were considered flukes as the Canuck squad regained the lead the next year. Canadians just assumed that only they could really play the game and became very complacent under this attitude. Reports of greatly improving Europeans were scoffed at my most “experts.” No one worked out in the summer nor did they do much dry-land training in season. When training camp arrived in September most just counted on playing themselves into shape.

But, starting in 1962 the Soviets first, then the Czechs, then the Swedes took turns at winning the gold. We comforted ourselves with the idea this state of affairs only applied to amateurs. The pro NHL is what was really important. We noted the International rules limited body checking. Since our pros were experts at intimidation we assumed that if we could only play them with “our” rules things would be different. Since that would not happen soon, we could always reassure ourselves of our “real” superiority. But as the 1960s wore on it soon became apparent that even our best amateurs could not do the job anymore. We had to concede that a new day had dawned. We were not the best amateurs any more.

Our fall-back position was that they would still never beat our pros. They just knew they weren’t big enough, fast enough, skilled enough, and especially not tough enough (the much vaunted Canadian nice-guy image is not operative in hockey). We also realized the officially amateur Soviets were in fact professionals since they trained full-time at Red Army expense. This provided a serviceable excuse when losses became commonplace. Unbeknownst to us our egos were also protected by the amateur rules forbidding games with professionals. We still too-confidently assumed that OUR pros would clobber them if only they ever were to meet. Canadian fans craved such a meeting where they could show the world their superiority once and for all. The fact this would raise a lot of rubles did much to finally bring this about.

Our fall-back position was that they would still never beat our pros. They just knew they weren’t big enough, fast enough, skilled enough, and especially not tough enough (the much vaunted Canadian nice-guy image is not operative in hockey). We also realized the officially amateur Soviets were in fact professionals since they trained full-time at Red Army expense. This provided a serviceable excuse when losses became commonplace. Unbeknownst to us our egos were also protected by the amateur rules forbidding games with professionals. We still too-confidently assumed that OUR pros would clobber them if only they ever were to meet. Canadian fans craved such a meeting where they could show the world their superiority once and for all. The fact this would raise a lot of rubles did much to finally bring this about.

In 1972 we finally got our wish. The eight game Summit Series that fall was a landmark in our attitude change. Most experts assumed it would be a blow-out. That delusion lasted for about half a period. Canada scored early in the game, but then lost the game 7-2. Canada ultimately won the eight game series, but just barely. Most celebrated as if we were vindicated, but deeper thinkers knew otherwise. A lot of illusions died that September. No longer could we fall back on all of our former excuses for losing or our assumption that others could not play the game like us. To the credit of the Canadian hockey establishment much more serious coaching was instituted along with dry-land training, systems study, and a trend to bigger and stronger players.

It worked, but only to a degree. We eventually started winning the big ones again, much to the relief of sport fans who assumed our days of hegemony soon would return. Despite such optimism we never did regain domination of the game. Too many other countries were then doing the same things as international sporting prestige drove all to excellence. Canada would begin winning World Championships again, but they could not count on doing so every year. A certain degree of hockey power parity had been reached just as had happened in the economic powers a century ago.

It worked, but only to a degree. We eventually started winning the big ones again, much to the relief of sport fans who assumed our days of hegemony soon would return. Despite such optimism we never did regain domination of the game. Too many other countries were then doing the same things as international sporting prestige drove all to excellence. Canada would begin winning World Championships again, but they could not count on doing so every year. A certain degree of hockey power parity had been reached just as had happened in the economic powers a century ago.

By now the more observant readers will see how this connects with the weight sports. Bud Charniga has written very extensively of how the USA’s much cited superiority in Olympic lifting from 1946 to 1959 was based on the absence of many European nations still recovering from WWII. Contrary to common assumption that was not the natural state of affairs. Over the decades since then many pundits have yearned for an American restoration in Olympic lifting superiority complete with their simplified prescriptions on how this can be brought about. In fact, if any such revitalization does occur it would likely only result in the USA taking a certain share of the medals but not to the degree of the Hoffman heyday.

A degree of parity has been achieved in weightlifting, just as happened in hockey. The old USSR has devolved into a number of successor states. None are now as strong as the old USSR but they are still way ahead of most others. Many other countries have joined the elite in recent years, all at the expense of the formerly dominant Soviets and Bulgarians. They all now stand in the way of a second US Golden Age. This would not be impossible to achieve (nothing is) but it certainly is not probable given the systemic problems facing them.

And just in case any powerlifters are still reading they will back my observations up. The USA ruled that sport for many years but unlike the quick lifts they are still to be reckoned with. They never had to consider the Eastern Europeans in days gone by but now the latter and others have broken THAT monopoly. No American goes to the worlds assuming he or she will come home a world champ.

The lesson here is that competition makes us all better but we cannot guarantee that we will be the only ones better when all is said and done. Just ask an old Scottish shipbuilder.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.