Many athletes and coaches believe that skill work alone will create the best athlete. However, despite a slow change in the opposite direction, some coaches are stuck in their ways and perhaps need more convincing. In a recent study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, young soccer players traded off some of their practice time for exercise to see what would happen.

Sometimes the sport you play isn’t good at developing all of the attributes that are important for success, so honing a wide variety of abilities is critical for all athletes. But time is limited, and so the age-old concept of the priority of skill work over other training often takes precedence. While generally true, if an athlete never works on general attributes, their success may be stunted.

In this study, researchers created a program that was designed to be done anywhere and would replace a portion of the athlete’s normal practice, but not too invasively. The program lasted twelve weeks. The control group performed their normal training regime and game schedule. Although the researchers didn’t specify what constituted the training of the control group, it seemed to be only soccer practice and nothing else.

The group that performed contrast training, on the other hand, replaced some of their drills twice per week with a few isometric and plyometric exercises. The contrast training consisted of an isometric squat (similar to a wall squat), with the knees at a ninety-degree angle, and a variety of jumps. The jumps included jumping from a seated position and single leg jumps, among others.

Prior to this training program, the players underwent a battery of tests such as sprints, jumps, agility drills, and kicking. After the training they went through the tests again to see which group had improved more.

Both the control group and the contrast training group improved in the straight running tests. The five-, ten-, twenty-, and thirty-meter runs all significantly improved, no matter which program was chosen. However, vertical leap, agility, and kicking speed all improved in the contrast training group only. Since jumping was included in the contrast training, vertical leap improvements are hardly a surprise, but with agility and especially kicking speed being closer to actual game occurrences, it’s nice to see those improved, too.

There were a few interesting aspects of this study. First of all, the length of the training protocol was unique. At twelve weeks long, it’s longer than most studies of its kind. This is good to know, because it seems the benefits yielded by contrast training will persist by the twelve-week mark. It may be the case that this training won’t continue to yield fruit beyond this point, but that has yet to be determined.

The second interesting bit about this study is that there was no external load used during the contrast training. This means the extra benefit of this type of training can be realized from anywhere. The exercises used in this program require only a wall or something to sit on. Because it’s been shown effective, its simplicity and accessibility make it a powerful method.

So, when coaching young athletes, and indeed probably older athletes as well, mixing up your training seems to be an effective way to improve skills. If all of an athlete’s exercise comes from skill work, it may be beneficial to trade some of it for more varied exercise like plyometrics or isometrics.

References:

1. Felipe García-Pinillos, et. al., “Effects of A Contrast Training Program Without External Load on Vertical Jump, Kicking Speed, Sprint and Agility of Young Soccer Players,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000452

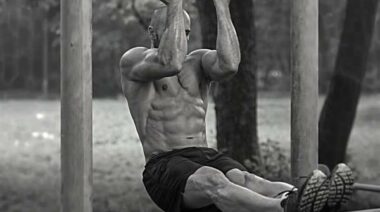

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.