In many sports, especially combat sports, the use of restricted breathing in various forms, has become quite popular. In a recent study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, the practice was put to the test.

So far, the research on respiratory training has had mixed results. Recall the popularity of elevation training, for example, and how it has come under fire in the last few years. In fact, the respiratory system isn’t often considered a limiting factor for athletic performance. While your muscles may fail, your blood can accumulate waste products, and even your mind may tell you to quit, the lungs and respiratory muscles don’t seem to have much to do with athletic failure. The primary muscle of breathing, the diaphragm, isn’t prone to fatigue.

Nevertheless, it seems that respiratory training does yield changes in the response of the lungs to exercise. The researchers of the Journal study deemed it a topic worth checking out, particularly considering the popularity of the various methods of respiratory training.

In the study, the researchers used rugby players so they could perform the tests on conditioned athletes. They used two different kinds of shuttle runs. One was a fairly standard shuttle run in a twenty-meter grid. The second run was on the same grid, but involved a defensive roll. The participants dropped to the ground, rolled to their back, and rolled to their chests again before standing up and continuing the run.

The researchers measured blood lactate levels and respiratory function before and after the shuttle runs, and also tracked heart rate and perceived exertion during the runs. In each type of shuttle run, the participants either wore a nose clip to restrict their nasal breathing, or they ran the shuttle runs normally.

In the end, there was no difference between the restricted breathing condition and the normal condition. That goes for blood lactate, heart rate, and other factors during both shuttle runs. Restricted breathing simply didn’t seem to make a difference.

Keep in mind, however, that the study only tested nasal restriction. That’s not a huge restriction, and as a coach myself, it’s not one I see employed as commonly as some other methods. The researchers indicated that the combination of restricted nasal breathing and a snorkel to partially restrict mouth breathing might increase acidosis, which would allow athletes to potentially increase tolerance for that common athletic condition.

Ultimately, such a limited restriction may not have a big effect on performance. Additionally, it may also not represent the actual conditions athletes find themselves in, particularly combat athletes. Perhaps further restricting breath could be of benefit, but until something conclusive comes out, you’re better off practicing your sport instead.

References:

1. Rudi Meir, et. al., “The Acute Effect of Mouth Only Breathing on Time to Completion, Heart Rate, Rate of Perceived Exertion, Blood Lactate, and Ventilatory Measures During a High-Intensity Shuttle Run Sequence,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(4), 2014.

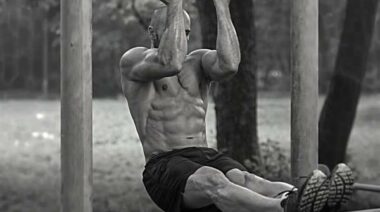

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.