As a trainer, a question I am asked is whether cycling or running is better. The answer is an easy one, but not simple: it depends. Which do you like better? That’s probably the correct answer for most people, but not always a complete answer.

When asking the question of “what is better?” you need to always first consider the traits that make something better or worse. In other words, what are your goals? For cardiovascular fitness, running and cycling are both excellent. Cycling may take longer for some athletes to be able to maintain a good effort. Running is cheaper, but cycling will get you somewhere faster if you use it for transportation. Determining which of these traits are most desirable or undesirable is the first step to deciding which activity is going to be better for a trainee.

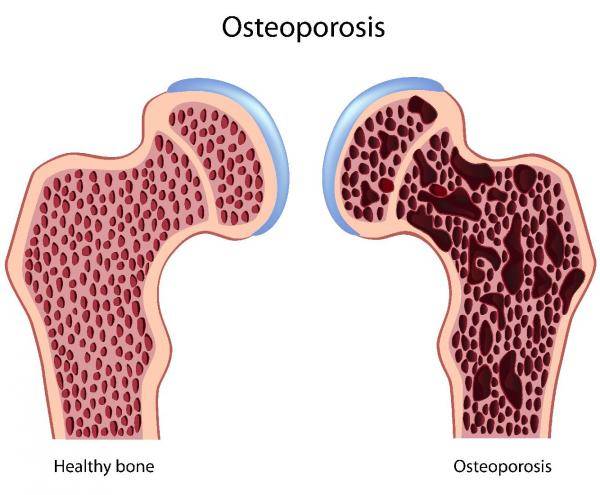

One often-overlooked aspect of exercise that is important for many trainees is the impact on bone health. Having a favorable mineral profile, density, flexibility, and strength in your bones is important to all athletes, especially aging athletes or those involved in high-impact sports. The way you exercise can make a substantial difference to your bone health, sending you into your older years better prepared and with fewer bone breaks.

According to a review published in BMC Medicine, when asking if cycling is better for bone health the answer is very clear. It is not. In fact, two thirds of all professional and masters level cyclists can be considered osteopenic, which means they have lower than average bone density. Osteopenia is considered a precursor to osteoporosis.

Now, before jumping to the conclusion that cycling causes osteopenia, I want to say it’s important when looking at results like this to consider alternative perspectives. Perhaps having low bone density means having lower bodyweight, and the reason pros have lower bone density isn’t because they are really good cyclists, but rather they are really good cyclists in part because of their lower bone density. Less weight is an advantage in cycling. Not as much advantage as in running, but runners have higher bone density for other reasons. It’s the impact and weight bearing aspects of exercise that increase bone density and mineralization, so the nature of running makes athletes have stronger bones. With that in mind, however, I don’t think it’s a big enough justification to assume that cycling isn’t potentially detrimental to bone health. At the very least it won’t help your bones.

Now, before jumping to the conclusion that cycling causes osteopenia, I want to say it’s important when looking at results like this to consider alternative perspectives. Perhaps having low bone density means having lower bodyweight, and the reason pros have lower bone density isn’t because they are really good cyclists, but rather they are really good cyclists in part because of their lower bone density. Less weight is an advantage in cycling. Not as much advantage as in running, but runners have higher bone density for other reasons. It’s the impact and weight bearing aspects of exercise that increase bone density and mineralization, so the nature of running makes athletes have stronger bones. With that in mind, however, I don’t think it’s a big enough justification to assume that cycling isn’t potentially detrimental to bone health. At the very least it won’t help your bones.

So let’s examine the results. Cyclists have consistently lower bone density and content in the lumbar (lower) spine compared to pretty much everyone else, whether other athletes or non-athletes. Also, pelvic, hip, and femoral (the big bone in your leg) values are consistently reduced, and these are major areas of concern for breaks, especially in aging people. Relative to other sports, high impact falls are a major concern for cyclists as well. And the older the athlete, the bigger the difference, so the effect may worsen with time.

Now let’s not get too carried away with these results. Inactivity is associated with poor bone health as well, so if you love cycling or are a professional, this isn’t a doomsday prophecy. Cycling seems to be of little detriment to those who do it recreationally. If you are at risk for osteoporosis, or if you’re a professional, you may want to include both weight bearing exercise (e.g. weight lifting) and impact exercise (e.g. running) into your routine to help balance the impact on your bone health. As long as you pay attention to your bone health while cycling there’s no reason to not do what you love.

References:

1. Huge Olmedillas, et. al., “Cycling and bone health: a systematic review,” BMC Medicine, 10:168 (2012)

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.