Believe it or not, any exercise plan you successfully used in the past was supported by the following principles (otherwise, you wouldn’t have improved or observed results):

- Overload

- Recovery/Adaptation

- Progression

Believe it or not, any exercise plan you successfully used in the past was supported by the following principles (otherwise, you wouldn’t have improved or observed results):

- Overload

- Recovery/Adaptation

- Progression

Think about a time when you were seeing noticeable improvements in your endurance or increases in your strength. Somewhere along the line you were creating a stress on the cardiovascular system and/or your muscles via physically demanding workouts. This was the overload principle. The off-time between these demanding workouts allowed your body to improve or grow in response to the imposed stresses. This was the recovery/adaptation principle. Now, being in better shape and/or stronger, you were able to handle higher levels of stress. You gradually “did more” in your workouts even though it may have been small, incremental stress applications. This was the progression principle.

Essentially, you worked hard, gave your body time to rest and heal, and were able to do more as a result. You might not have had a specific, in-writing training plan that followed these long-standing principles of training, but you did it.

There is one principle some trainees need to shore up a bit. The progression principle is where many fall off the cliff. It’s time to revisit this often-neglected underpinning of a successful exercise plan as it applies to conditioning workouts.

Many trainees work their butts off, rest and eat sensibly, but fail to have progressive plan in front of them. You cannot hit the running trail, run intervals, or boot camp-it in the same manner over and over without upping the ante gradually. If your bodyweight circuit workout uses the same exercise, reps, and workout time, you’re getting nowhere. Run, bike, or swim the same distance at the same time/pace again and again and you’re also on the flat-line path to nowhere.

Doing more does not have to be complicated. In fact, it can be very simple provided you take a little time to plan it out. Let’s look at a few conditioning progression options (i.e., running, cycling, swimming, circuit training, etc.). There are four variables that can be manipulated in a number of ways to assure progression in conditioning workouts:

- Volume – the number of bouts (runs, reps) performed.

- Intensity – the level of physical effort expended.

- Duration – this could be two things: the length/distance of each bout and/or the time of each bout.

- Recovery – the rest time between bouts, if applicable.

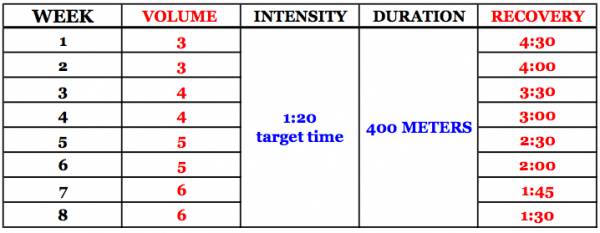

Using interval running as an example, take a look at this first chart to see all the possible options for progression. Over an eight-week period, for example, you could manipulate the variables weekly to assure you’re still challenging yourself. As you can see, it could be one, two, three, or all four variables altered over the training period.

Here is an 8-week progression example with only volume and recovery altered and intensity and duration remaining constant:

For circuit-type exercise modes (non-running, biking, swimming, etc.), the same thing applies:

- Increase the number of stations/exercises.

- Increase the intensity of effort.

- Increase the work period time.

- Decrease the rest time between stations/exercises.

For continuous modes of exercises such as distance running or work on an exercise machine (i.e., elliptical), it’s the same:

- Work longer at the same pace.

- Work harder at the same time/distance

- Work longer and harder.

The bottom line on conditioning progression: have a plan that requires you to do more bouts, work harder, work longer, and/or decrease rest time between bouts. Plan it out. Write it down. You’ll be doing yourself a huge favor.

And what if you’re trying to get stronger? Well then check out the Idiot’s Guide to Progressive Strength Workouts.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.