In an ongoing effort to educate myself about the roots of the martial art I love, I recently watched the 1999 documentary Choke. In academese, you could say that Choke is a historical document, a primary source that provides insight into an important moment in grappling history and captures the charisma and extraordinary talent of one of grappling’s most famous ambassadors.

Plus, the fight scenes are badass.

Directed by Robert Goodman, Choke chronicles the preparation of three fighters for the 1995 Japan Open, a vale tudo (“anything goes”) event. The featured fighters were Rickson Gracie, who was preparing to defend the freestyle fighting title he had won in 1994 and is one of the best-known figures in Brazilian jiu jitsu, oh, and two other dudes.

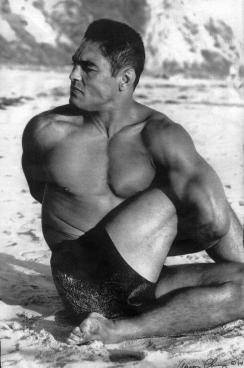

Just kidding. The other guys were American Todd Hays, who fought out of Oklahoma, and Japanese contender Koichiro Kimura. The reason I sort of glossed over them is twofold. First, I’m biased toward grapplers in general, and second, there is just something legitimately compelling about Rickson Gracie. You have to watch him, whether he’s training jiu jitsu, coining quotable quotes that capture many practitioners’ beliefs and feelings about it, or demonstrating his other physical abilities (including a really impressive, and somewhat alien-seeming, display of breathing control). I can’t say for sure that non-grapplers would feel the same, but given his eloquence in describing his love of jiu jitsu in terms of what it affords him in life, perhaps they would.

And anyway, the title, coupled with the fact that Rickson’s grappling ability has taken on almost mythic proportions (in grappling circles it is spoken about in hushed tones and behind respectfully lowered eyes), further communicates this movie is Rickson’s, with the vale tudo event and the other competitors simply the backdrop/rationale for a closer look at him. I had heard some of his better-known comments about jiu jitsu (including the much-adored “You pretty much flow with the go”), and the movie combines many of them in one place for easy consumption and further contemplation.

For instance, consider this eloquent encapsulation of the “it” about Brazilian jiu jitsu: “The most interesting aspect of jiu jitsu is the…sensibility of the opponent, the sense of touch, the weight, the momentum, the transition from one movement to another, that’s the amazing thing about it.” And he gets at the ineffable when he says, “I feel myself as an artist. I like to do things because it’s (sic) beautiful, it’s intense, it’s edgy…I like to put my energy in life, in intensity.” The point is every white belt on the planet likely has these thoughts and feelings about BJJ (thoughts and feelings that stay with them through their entire BJJ journey) but perhaps not the insight or the language to express them. This is why Rickson is Rickson and the rest of us are, well, not.

For instance, consider this eloquent encapsulation of the “it” about Brazilian jiu jitsu: “The most interesting aspect of jiu jitsu is the…sensibility of the opponent, the sense of touch, the weight, the momentum, the transition from one movement to another, that’s the amazing thing about it.” And he gets at the ineffable when he says, “I feel myself as an artist. I like to do things because it’s (sic) beautiful, it’s intense, it’s edgy…I like to put my energy in life, in intensity.” The point is every white belt on the planet likely has these thoughts and feelings about BJJ (thoughts and feelings that stay with them through their entire BJJ journey) but perhaps not the insight or the language to express them. This is why Rickson is Rickson and the rest of us are, well, not.

The film weaves together footage of the three competitors as they prepare for the event, including talking head testimony from coaches, family members, and athletes themselves. During a visit to a radio station where Rickson is scheduled to participate in an interview prior to the event, a photographer tells Rickson that he (the photographer) would come to Japan to see the event if he could because, “With you, I’m watching history.”

Still and all, the rest of the bouts in the eight-man event are exciting to watch too. Yuki Nakai, a contender who weighs maybe 130 lbs., bests not one, but two opponents who are virtually twice his size, dispatching Gerard Gordeau with what is referred to in the film as a “knee lock,” and Greg Pittman via armbar. Though he does not escape unscathed, sustaining bruises around his eyes that almost swell them shut, Nakai’s wins secure him a spot in the final against Rickson.

For his part, Rickson survives a guillotine attempt by Yoshihisa Yamamoto before taking him down, mounting him, taking his back and finishing him with a rear naked choke. He then does basically the same thing to Kimura, who breaks down in tears during his post-fight interview, describing the experience of fighting Rickson: “I’ve come to understand the enormous depth of Gracie jiu jitsu. It’s not simply a blend of wrestling and judo. His is an entirely new discipline that I want to understand as much as I can…Please leave me alone now.”

In the end, Rickson, who had decided ahead of time he did not want to punch Nakai due to the damage the latter had already sustained in his earlier fights, took Nakai down, passed his guard, and took the mount in a decidedly authoritative manner before eventually taking his back and executing – you guessed it – a rear naked choke.

In the end, Rickson, who had decided ahead of time he did not want to punch Nakai due to the damage the latter had already sustained in his earlier fights, took Nakai down, passed his guard, and took the mount in a decidedly authoritative manner before eventually taking his back and executing – you guessed it – a rear naked choke.

In addition to being a fun showcase of vale tudo, Choke remains relevant today in terms of its messages, about fighting and about life. It is a historical artifact, but it can provide present-day grapplers with a bit more understanding of the history of their art and how they might be able to honor and contribute to it. So much of what’s in the movie rings true, even close to twenty years after the event. This is what makes a classic a classic.

Check out “Choke” yourself – you can watch the whole thing on YouTube – and post your reactions to comments below.