Who has a cranky shoulder (or two)? Raise your hand… or don’t if it hurts.

Nearly every athlete or lifter who’s trained for more than a couple years inevitably tweaks a shoulder. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, it hurts for a few days and then it’s gone. If you’re not so lucky, that twinge sticks around for years and you may even carry the hefty label of “shoulder impingement.”

This article will provide you with a few ideas for training around an injured shoulder and potentially even eliminating that twinge over time (depending on the source).

Let’s Talk Anatomy

First, let’s identify the major anatomical players we’re going to discuss:

- Scapula – the shoulder blade

- Humerus – the upper arm bone

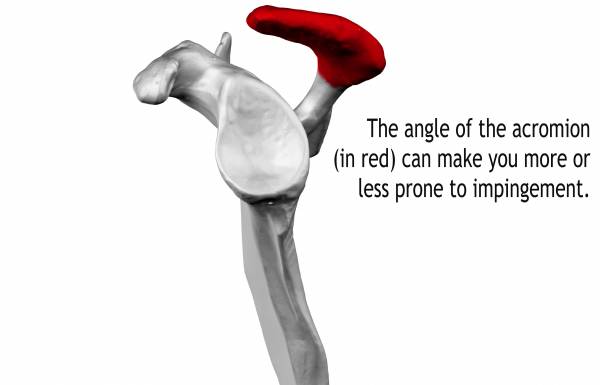

- Acromion – the bit that sticks up from the shoulder blade and comes toward the front of the shoulder

The scapula, humerus, and acromion are the major anatomical players we’ll discuss today.

Most often, “shoulder impingement” is the diagnosis for shoulder pain. Shoulder impingement typically comes in two flavors:

- External – pain manifests anteriorly (front of the shoulder)

- Internal – pain manifests posteriorly (back of the shoulder)

The most common type of pain is in the front of the shoulder so the methods and exercises discussed here will be geared for those with external impingement/anterior shoulder pain. But before you proceed, you also need to be aware of whether your pain comes from primary or secondary impingement.

Primary vs. Secondary Impingement

Ever notice how some people can bench press until the cows come home and yet never seem to have shoulder pain? If I did that, my shoulders would be screaming within a month. Primary impingement is a result of structure or anatomy. For example the angle of the acromion will determine the size of the sub acromial space (the gap beneath the red bit below).

Depending on the angle, if your sub acromial space is smaller, it’s much more likely you’ll wind up pinching one of the many tendons that run through it. This little difference means some people can bench press forever without pain and some of us will have a perpetually tweaked shoulder no matter what they do. There will be certain movements that will always cause problems purely based on your anatomy.

“Primary impingement is a result of structure or anatomy. For example the angle of the acromion will determine the size of the sub acromial space.”

Secondary impingement is related to things like lack of mobility, scapular position, muscle tightness or stiffness, etc. and can be reversed if you improve these aspects through dedicated strength and mobility work. The substitutions listed below are great ways to continue training while you work on your mobility and let your shoulder heal. Increasing the amount of pulling versus pushing in your training can play a role, too, and there’ll be more on that later.

A Word of Caution

How to diagnose your shoulder pain – as primary or secondary – is outside the scope of this article. Unfortunately, the only way to truly know your anatomy is via x-ray or MRI. That said, it’s a safe bet that if you inevitably tweak your shoulder every time you overhead press, it’s best to stay away from that entirely.

Most people with shoulder pain probably already know what they can and can’t do. Be aware that the exercise substitutions below are general ideas and you should add or eliminate according to how your shoulder feels. You should also talk to a health practitioner if you’ve been experiencing chronic pain.

A Little Attention to Form

Before we talk about avoiding and substituting exercises, let’s briefly touch on position and form. If you are unable to achieve the proper position for a lift, say the overhead press, it will be tough to prevent injuries when doing that movement. Check out your shoulder mobility first – and then actually work on it – before loading up the military press.

When it comes to movement form, horizontal pressing and rowing can irritate the front of the shoulder if your rows look like the first two reps in this video. Instead, strive to imitate the form of the last two reps.

What you saw in the first two reps is called anterior humeral glide. It’s when the humerus (upper arm bone) drifts forward in the socket (it looks like it’s popping out in the front) and, as a result, all kinds of friction happens within the joint. Too much friction and – boom! – you wind up with angry shoulders.

Pay attention to how you’re performing your rows and presses and it will go a long way toward maintaining healthy shoulders.

Exercises to Avoid

- Overhead pressing

- Lateral and front delt raises

- Upright rows

- Bench pressing

- Pull ups

- Dips

- Back Squats

If you’re sharp, you’ll notice a common theme among these particular exercises. They entail one or both of the following:

- Humeral flexion – arm going over your head, as in the overhead press

- Humeral abduction – arm going out to the side, as in lateral delt raises or upright rows

Movements like the overhead press or lateral raise can close off the shoulder joint, particularly that pesky sub acromial space, which leads to tendons getting squished. The pronated grip (palms down) of pull ups and bench press also close the shoulder joint more than exercises done with a neutral grip.

Dips are the worst offenders, though. They automatically force the upper arm (humerus) forward in the socket, so we find ourselves in that anterior humeral glide – perfect for rubbing and pinching tendons.

Back squatting may or may not bother you, depending on your shoulder and thoracic spine mobility. But if you’re lacking in either, the typical arm position required by back squatting can be compromising to already tender shoulders.

Exercise Substitutions and Modifications

- Landmine pressing

- Push up variations

- Dumbbell floor presses

- Neutral grip chin ups

- Front squats

Note: You should still avoid front squats if you have an AC joint issue.

Landmine pressing is fantastic for people with cranky shoulders. This movement provides a semi-overhead angle while not requiring full-range shoulder mobility.

If you miss pressing, you can also give supine landmine pressing a whirl.

Push ups are almost always an acceptable substitute for horizontal pressing. The advantage of push ups over barbell or dumbbell work is the shoulder blades are able to glide freely on the rib cage. When you bench or dumbbell press, the scapulae (shoulder blades) are pinned down against the bench. As you bench, your humerus is moving independently from your shoulder blade, which is more likely to result in impingement because the humerus jams up into the acromion. In contrast, push ups allow for a free-moving scapula that moves along with the humerus and thus reduces the likelihood of impingement.

“Doubling your row volume relative to pressing volume can sometimes relieve shoulder pain and prevent it in the future.”

If you think you’ll shrivel up and die without some sort of press, dumbbell floor presses are the way to go. The floor prevents the elbows from traveling past the body (and thus prevent anterior humeral glide) and you can use a neutral grip with dumbbells, which keeps the sub acromial space open. The same can be said about neutral grip chin ups. The more open grip allows for more wiggle room under that acromion.

Reconsider Ratios

Many workout programs incorporate a press-to-pull ratio of 1:1. When you have an injured shoulder, one training modification you can employ is to increase the ratio in favor of rowing, to more like 1:2 or 1:3 press-to-pull. Sometimes pain is simply an imbalance between front and back and increasing the rowing volume can solve your issue. For example, when pairing push ups with bent-over rows, you would perform twice as many sets of rows as you would push ups. You may find that after a few weeks your shoulder pain clears up.

The Take-Home

While this article is not even close to exhaustive, you should find a couple of tips that can help keep you and your shoulders happy.

- Remember to be mindful of the way you perform your presses and rows to avoid anterior humeral glide.

- Avoid exercises that require humeral flexion and abduction (arms overhead and arms out to the side) like the plague – at least for a few weeks while your increase the strength of your upper back muscles.

- Doubling your row volume relative to pressing volume can sometimes relieve shoulder pain and prevent it in the future.

As I’ve said before, you should walk out of the gym feeling like a superhero, not painfully grimacing as you drive home.

More Like This:

- Not the Rotator Cuff: The Truth Behind Most Shoulder Injuries

- A Simple 4-Step Mobility System for Every Lifter (and Every Lift)

- What’s New On Breaking Muscle UK Today

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 by By BodyParts3D is made by DBCLS, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 courtesy of Kelsey Reed.