If you close your eyes and imagine your entire right arm, from your fingertips all the way up, where does your image of your arm stop? Does it include your collarbone or your breastbone? What about the shoulder blade? Was that part of your image?

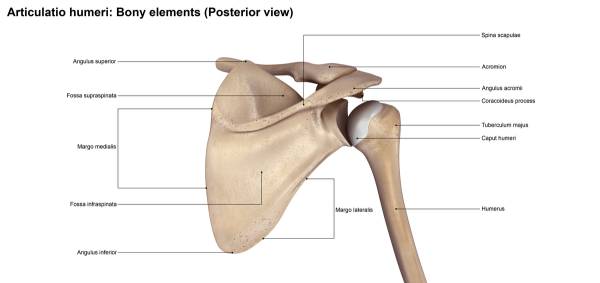

The shoulder joint is complicated. It consists of connections between the upper arm bone (humerus), the shoulder blade (scapula), and the collarbone (clavicle). The arm is allowed to go overhead because of an interplay between these bones, as well as the act of the scapula moving over the ribs and the clavicle moving at the breast bone (sternum).

Because of its complexity, it shouldn’t be terribly surprising people struggle with this area. Add into the equation the fact that the joint is quite shallow, which results in a sense of instability, and you’ve got a joint that’s seriously misunderstood.1

A survey of 29,026 people in Norway found 15.4% of men and 24.9% of women experienced shoulder pain on a weekly basis.2 Pain is a nuisance and limits your everyday activity. For those of us that are active, shoulder pain can decrease our quality of life in a debilitating way.

Let’s assume that if you have pain or discomfort, you have been checked out by a medical professional and told there is nothing physically wrong with your shoulder. We’ll look at both the inability to take the arm overhead because of stiffness or discomfort, and the inability to take the arm overhead because it feels unstable. But first, let’s talk about how the motion of taking the arm up happens.

How Do the Arms Go Up?

For the purposes of this post, let’s assume the arm starts at the scapula. When we take the arm overhead, the scapula externally rotates, posteriorly tilts, and upwardly rotates, while the clavicle elevates and retracts.3 In plain English, when you take your arm overhead, the shoulder blade rotates out and up while the collarbone lifts up and back. It’s like there is a loop from the collarbone all the way around to the shoulder blade. What happens at one changes the position of the other, and both allow the necessary space to be created for the arms to move upwards.

One common issue I see with overhead movement is the inability to differentiate the shoulder from the ribs. Instead of letting the arms go overhead by letting the scapulae move, often people will lift the front of their ribs. If the ribs are held down, the arms (usually) don’t go as far, indicating a mobility, strength, or motor control issue.

Think about all of the times you have been told to keep your shoulders “down and back.” For the shoulder to function optimally, it’s important to be able to do the opposite of down and back. The shoulder blade is not a fixed object; it allows the arm to move freely.

Learn to Feel Your Shoulders

The tricky part about this is you can’t see your shoulder blade, which can make feeling how the shoulder blade moves an obscure concept. Fortunately, there are ways to improve overall awareness of the back of your body. When I teach, I follow a basic model: bring awareness to what a specific area feels like, teach the area how to move and how to be still, and then strengthen and mobilize. You can’t change what you can’t feel, and the shoulder area is no exception.

An easy way to begin feeling how the scapula works with the arm is to lie on your back and move the shoulder up, down, towards the ceiling, and towards the floor. You should begin to feel the shoulder blade moving against the floor. You can also take the arm up towards the ceiling. Keeping the arm straight, exhale and reach the hand towards the ceiling. You should feel your shoulder blade move away from the center of the back. Still keeping the arm straight, lower the shoulder back to the floor. Perform 6-8 reps per side.

Once you have mastered what it feels like on your back, flip over into a hands and knees position. Exhale, let your shoulder blades move away from each other. Inhale, let them come towards each other. Not sure whether you are moving your shoulder blades? Try this: exhale, let your back round into a cat position. Your shoulder blades will naturally move away from each other. Inhale, let your back arch. Your shoulder blades will come towards each other. Once you have done a few by rounding and arching your back, see if you can keep your back still and move just from your shoulder blades.

Breath Control and Shoulder Movement

Breathing and shoulder mobility go hand in hand. The muscles that help you breathe when you are stressed out can technically be any of the muscles that attach to the ribcage.4 Coincidentally, a lot of the muscles that attach to the rib cage connect either to the head or arm. If you consistently breathe like you are preparing for the zombie apocalypse, chances are high you won’t have a lot of freedom to move at the shoulder.

There are a number of specific breathing drills that can calm the nervous system down and alter breathing habits. One of the easiest ways to influence breathing is by inhaling through the nose for a count of four, and exhaling out the mouth for a count of eight. You can do this sitting, standing, or lying down. As you exhale, observe how your ribs soften down and in. When you inhale, instead of letting the ribs flare up, let your air move forward, back, and to the sides. Take 4-6 breaths before you begin your workout. This creates awareness of rib position and makes it easier, when you take your arms overhead, to make sure you don’t lift at the ribs, isolating the arms instead.

Motor Control in the Shoulder

Once you have a good idea what the shoulder blades feel like, it’s time to work on taking the arm overhead. But first, let’s take a moment to understand what it feels like to have a sense of co-contraction in the shoulder.

There are four little muscles that stabilize the shoulder in the socket. These are considered the rotator cuff muscles. There are also several muscles that control movement of the arm in different directions. The ability to feel an even distribution of load across the shoulder involves a sense of co-contraction in the stabilizing muscles, as well as balance across the front and back of the neckline. It’s as though the collarbone and the top of the shoulder blades reach out evenly, until eventually they join at the top of the shoulder. The video below offers a brief explanation of how to feel this co-contraction.

The concept of co-contraction will usually aid in a sense of stability throughout the shoulder joint. One way to practice moving the arms overhead while keeping this sensation is to draw on what you learned from the exercise above. Remember what it felt like to gently pull the dowel apart? Come onto your hands and knees. Do the same action of pulling the dowel apart with your hands, except now you’ll push as if you are trying to spread the mat apart. Keep this action as you rock your hips back and bring your hips back to center.

Another option is to set up on hands and knees and imagine there is a line running from the inside of your armpit down to your thumb and from the center of the shoulder down to the pinkie. See if you can organize yourself so those two lines are the same length and you are creating as much length as possible between the wrist and the shoulder. Once you have that, see if you can do the same action of moving your hips back towards your heels as you exhale; as you inhale, return to center.

Which of these cues works best will depend on your habits. If you have a difficult time fully straightening the arm, you might respond really well to the idea of your inner arm and outer arm becoming the same length. If you have elbows that hyperextend, you might do a little better imagining you are pulling the mat apart. However, these rules aren’t set in stone. Play with them and see what works best for you.

These cues work because they are using the arms and the muscles surrounding the shoulder girdle in a more focused way. Once you build the strength to hold these positions, typically, relying on the muscles in this way will be a little more efficient.

Your Ribs Are Not Shoulders

If you set up on hands and knees with your ribs moving towards the floor, all of the shoulder work described above will feel more difficult. This isn’t necessarily bad, but it isn’t efficient. If you can get the lower ribs to run parallel to the floor in quadruped, it will make it easier to isolate the movement of the arms going overhead when standing or in handstand. An easy way to get your ribs parallel to the floor is to exhale and feel how the ribs move toward the back. Now inhale, but don’t let the ribs move towards the floor. You will probably feel your abs, making this one of those positions that can accomplish multiple things at once.

You can also work on reaching the arm overhead from a forearm and knees position. Keep the sense of the hands lightly pulling away from each other and maintain a connection between the ribs and the pelvis. This keeps things out of the neck and allows the scapulae to upwardly rotate. Exhale as you reach the arm, inhale as you return it to center.

What Goes Up…

When you think about moving a body part, you probably focus on how to get the body part from point A to point B. For instance, when you think about taking the arm overhead, the image that comes to mind is probably what needs to happen to take the arm up. But what about taking the arm down?

Whenever you work on controlling a limb’s movement against gravity, you are working on strengthening the muscles eccentrically. When the arm is overhead, you have two options: let momentum pull it down, or slowly lower it down. Slowly lowering it down requires more overall tension in the muscle fibers than lifting it up does.5 Research suggests the higher load placed on tendons during eccentric training leads to stronger tendons. The end result to this type of training is feeling more stable and stronger in end-range positions, like when your arms are fully extended overhead.

There are a number of ways to add eccentric exercises into your routine. The exercise above on the forearms is both a motor control exercise and an eccentric exercise. Go slowly, and think about resisting the floor as you return the arm to a starting position.

The Simple Hang

Once you understand the mechanics that allow the arms to go overhead in a hands-and-knees or elbows-and-knees position, it’s time to see if it feels any better to go overhead holding onto a bar. It could be argued hanging is a fundamental position, one our shoulder girdles are designed to do.6 However, it requires a large degree of mobility, strength, and motor control. If you don’t trust your ability to place all of your weight on your arms, begin by hanging on a bar where you can leave your feet on the ground, bending the knees to allow more weight to move into your arms as you gain strength and mobility.

When you come into the hanging position, allow yourself to hang freely, with your arms near your ears. Make sure your ribs aren’t moving forward towards the wall in front of you. Once you have this position, you can practice pull-up prep by keeping your arms straight and pulling the bar down towards you. Your shoulders will move away from your ears and your scapulae will move down your back. Go back and forth between these two positions, letting your exhale move the shoulders down and the inhale move the shoulders up.

There is power in feeling your arms can go overhead safely, without a feeling of instability or stiffness. If you work on the fundamentals of the movement, breaking it down and understanding where the motion comes from, you will experience a greater sense of freedom and strength while hanging or with weight overhead. Whenever you struggle with a specific action, ask yourself, “can I do this in a different way that doesn’t hurt?” If the answer is yes, practice that for a little while. Once you’ve built confidence and strength, try it a different way. We are extremely adaptable organisms if we are given the opportunity to respond to progressive, specific challenges in a systematic manner.

References:

1. Gomberawalla, M. Mustafa, and Jon K. Sekiya. “Rotator Cuff Tear and Glenohumeral Instability.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 472, no. 8 (2014): 2448-2456.

2. Pribicevic, Mario. The epidemiology of shoulder pain: A narrative review of the literature. INTECH Open Access Publisher, 2012.

3. Andrews, James R., Kevin E. Wilk, and Michael M. Reinold. The Athlete’s Shoulder. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2008.

4. McConnell, Alison. Respiratory Muscle Training: Theory and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013.

5. Camargo, Paula R., Francisco Alburquerque-Sendín, and Tania F. Salvini. “Eccentric training as a new approach for rotator cuff tendinopathy: review and perspectives.” World Journal of Orthopedics 5, no. 5 (2014): 634.

6. Crompton, R. H., E. E. Vereecke, and S. K. S. Thorpe. “Locomotion and posture from the common hominoid ancestor to fully modern hominins, with special reference to the last common panin/hominin ancestor.” Journal of Anatomy 212, no. 4 (2008): 501-543.