Time management is a commonly avoided topic in fitness. For those of us that have school work, a job to hold down to pay for school, and still needing to make sure we stay fit and healthy, it’s not something that we can leave to chance.

Time management is a commonly avoided topic in fitness. For those of us that have school work, a job to hold down to pay for school, and still needing to make sure we stay fit and healthy, it’s not something that we can leave to chance.

We all have to learn to manage our time. That means knowing how many effectively useful hours in the day we have to do all the things that are important and making sure, also, we have time to recover on a mental and neurological level. We need to compress the time that we put into our work to make it efficient, and still have time to decompress so that we recover successfully.

During my undergraduate years at New York University, as a single male, I worked in the Student Health Center, leading a volunteer organization to reduce student stress, in addition, I was on the Division 1 Fencing team and took core classes related to my program on top of my already packed school schedule.

My coach required us to spend at minimum two days a week training outside of our team sessions and at least two days in the training room. I commuted one hour and thirty minutes to school and typically the same amount of time returning home. In addition, as a man of faith, I dedicated my Sundays to my family and church.

My Mondays could look a bit like this:

| Time | Activity |

|---|---|

| 6:00 am | Wake Up |

| 6:30 am | Begin Commute |

| 8:00 am | First Class of the Day |

| 9:30 am | Second Class of the Day |

| 11:00 am | Third Class of the Day |

| 1:00 pm | Work |

| 5:00 pm | Study/Homework/Life |

| 7:00 pm | Practice |

| 10:30 pm | Commute Home |

| 12:00 am | Arrive Home |

| 2:00 am | Maybe Sleep – REM Rebound Maybe |

Having such a compressed schedule, I began to feel as if there aren’t enough hours in a day. I attended a seminar by Donna O Johnson, PhD and it inspired me to ask: How many hours are in a day? What could I be doing wrong?

How Many Hours in a Day Can You Effectively Use?

There seems to never be enough time for anything that we want to do. The quick and fast answer is, you have 24 hours in a day, and if you take away sleep time that leaves you with your usable time. You sleep for 6 hours, that’s 18 hours to do everything else.

If it were that easy balancing your work and training life would be so much easier. It isn’t. So, we have to think about the stuff that we have to do that isn’t training. That could be simplified as grooming, commuting, leisure, eating, studies, work, and then, last but not least, life.

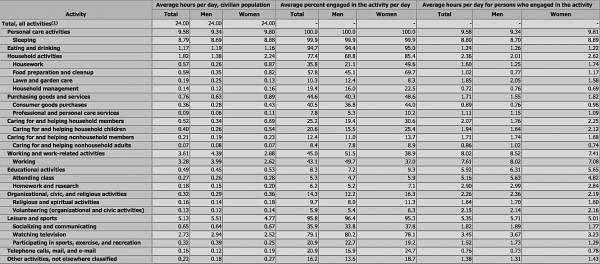

This is how the day looks, on average, for the US population[1]:

Click image to enlarge

Also, as a lone college student, I have other considerations. Gortner and Zuluaf show in their study on the academic use of time[2] that to significantly increase your GPA (more than a 0.025 increase) there is a substantial requirement to practice and study novel topics. So, now I have to add my extra study time.

Where do workouts fit in between the demands of everyday life, the extra demands of the once in a lifetime shot I get at a college education, and the need to pay for a full-time education?

The answer might surprise you. I have settled on three days of working out, 90 minutes each session, a day of rest in between, giving me time sufficient to manage my recovery and keep to my work schedule knowing I have some balance.

Push/pull splits are my personal choice here because I can work most muscles easily this way focusing on compound lifts and some accessory work. Typically, I break down my routines as follows:

| Day | Activity |

|---|---|

| Monday | Chest, Triceps, Quadriceps |

| Wednesday | Back, Biceps, Hamstrings |

| Friday | Calves, Shoulders, Hips, Olympic lifts for full body movements |

I just want to address the issue of posture in your workouts, too. According to Low and Ilano[3], “Students and those with desk jobs often need to develop greater awareness than those with more activity in their lives.”

This means more time integrating dynamic and static stretching. This, in turn, will reeducate the postural muscles namely: the SITS muscles, the posterior chain, muscles of the core and neck and lastly the legs.

Therefore, per 1.5-hour training session, 10-15 minutes should be dedicated to dynamic stretching prior to a routine, because static stretching cold muscles don’t have a great effect on muscle elasticity, neuromuscular patterning and heat generation in comparison to its dynamic counterparts. This too will aide in keeping the muscles fresh.

As your muscles mature and with more years of training under your belt, the amount of time needed will decrease and the type of work done should more closely mimic the exercise itself; if not the movement itself; such as pressing with an empty bar in a controlled fashion through the full range of motion for 1 minute and or using an empty bar to squat for a minute using full range of motion and testing depth. When testing depth, it accounts for other muscle groups that may need stretching as well.

Over time, you find time hacks, therefore, my experiences as a student will not necessarily be my experience in a different working environment. Adapting your time management processes probably never ends, but you do it so that you can stay on track with what matters.

Neurological Upkeep and Recovery

If time management couldn’t get any more complex, you must consider the amount of time your nervous system needs to recover, which includes stress management, which can be the hardest thing for most people to find time for.

It can take anywhere from 24 hours to 48 hours post-workout to fully recover. Obviously, this number varies from person to person, however, what is quantified, based on things like genetic markers, is your speed of recovery. Some signs that your recovery is not going fast enough are:

- Consistent and persistent fatigue from general activities independent of health issues

- Lack of Concentration

- Consistent decrease in power output during a routine

- Dizziness and extraneous heat production – feeling like your brain is going to fry in your skull

- Emotional lability

- Muscle pain – beyond soreness, whether it’s DOMS or debilitating

- Instead of increasing muscle tone, decreasing muscle tone and overall regression of gains

Therefore, if after 24 hours of rest your body is not back up to speed, note other factors such as your nutrition, sleep, and stress levels. Take breaks away from study material and time yourself, take a mental break from work. Break up your work with walks or downtime.

Training is a lifestyle choice. For me, it’s also a form of leisure. After writing an article like this I too need to time to decompress. Everything is relative. Make sure that you manage your time effectively, discipline yourself to stick to schedules and routines that are essential to your well-being. And, most importantly, give yourself time to recover and recharge, ready to do battle again.

Learn to make your priorities straight and everything else will follow. Train dynamically, my friends.

References:

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Average hours per day spent in selected activities by sex and day, 2016 annual averages.” 2017.

2.Gortner Lahmers, A., & Zulauf, CR (2000). “Factors associated with academic time use and academic performance of college students: A recursive approach.” Journal of College Student Development, 41(5), 544-556.

3. Steven Low and Jarlo Ilano, “Overcoming Poor Posture: A Systematic Approach to Refining Your Posture for Health and Performance.” pp 3, pg 7, pub Battle Ground Creative, Houston, 2017.

4. Shannon Clark, “How To Combat CNS Overtraining.” March 8, 2015.

5. Timothy J. Moore, PhD., “5 Ways to Deal with CNS fatigue.” April 15, 2016.