Inspiratory muscle training, or IMT, is a method of training the muscles that control the lungs. Anyone who has done wind sprints, so named for their effect on the lungs, understands the importance of these muscles. IMT alone can develop these muscles, just like resistance training develops your other muscles. But we don’t know whether or not IMT is more beneficial when it’s performed during training, when breathing rates are already high. A study this month in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research compared IMT during training and IMT done on its own.

The respiratory muscles are unique in that they are attached to the skeletal system, and yet they behave more like cardiac or smooth muscles, which are active constantly. This makes them the most active of all the large skeletal muscles. The effectiveness of these muscles seems to be without question, because breathing is not a limiting factor in exercise. In other words, when you exercise at your max, it’s not your lungs that make you give up, even though it sometimes feels like it.

Nevertheless, despite the fact that respiration is not considered a limiting factor in exercise, the development of these muscles through IMT all by itself does actually seem to improve performance. This may mean these muscles have athletic importance beyond just oxygenating the blood.

IMT itself is simple. It’s basically weight training for your lungs. When you breathe against resistance, such as with a device that requires forced inhalation, the muscles that control breathing get a workout and become stronger as a result. Because the breathing muscles are already worked harder when exercising, it’s possible that IMT works better during exercise than when performed on its own. Since there is a greater need for oxygen during exercise, practicing IMT during exercise might increase its athletic benefits.

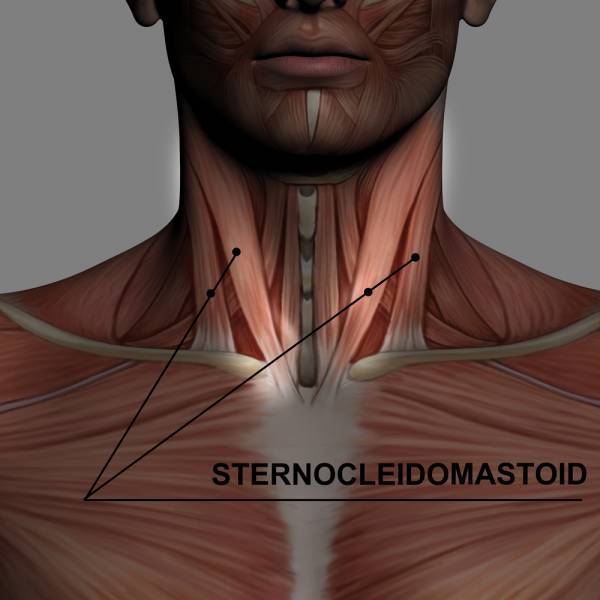

The researchers in the newest study used EMG to observe the effects of two muscles involved in respiration. The primary muscle was the diaphragm, a large, thin muscle inside the torso that inflates and deflates the lungs directly. The other muscle they observed was the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), a muscle that you are probably more familiar with by sight than by name. The SCM is the most obvious of the neck muscles when viewed from the front of a person, forming a V-shape from the top of your sternum up to the back of your ears. These muscles assist the diaphragm during respiration.

Cyclists were used in this study because they are able to use multiple postures, which also affects respiration. The researchers learned that moderate-level IMT during training works. It is more effective than IMT alone at activating both the diaphragm and SCM.

This study shows us that IMT during cycling does indeed work better at stimulating respiratory muscles than IMT alone. Although this study was done on cyclists, it’s a good bet it applies to any endurance athlete. The one exception may be swimmers, who get a similar benefit to IMT from water pressure. What the study doesn’t show us is if this added work is a further benefit to athleticism. We’ll have to wait for more research to answer that question.

References:

1. Nathan Hellyer, et. al., “Respiratory Muscle Activity During Simultaneous Stationary Cycling and Inspiratory Muscle Training,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, DOI: 10.1097/JSC.0000000000000238.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.