Every weightlifter can point to his greatest day in the sport. Usually this is a big meet where he set records, successfully did six for six lifts, or perhaps broke a major barrier like a 400lb jerk (or 200 for some of us). I had a few minor days like this, but the greatest day in my lifting career did not occur in a gym or on a competition platform. It did not even involve an Olympic bar.

My high water mark came one day in 1970 while working my summer job with the City of Calgary Parks Department. My crew was cleaning, sorting tools, and so on at our garage. One of the tractors pulled into the yard. On its front was a rack for some counterweights whose combined weight and forward position leverage was designed to prevent the unit’s driveshaft from climbing around the differential’s pinion gear and forcing the unit into doing a wheelie while under load. (I’m sure coaches can come up with weightlifting analogies if they think hard.) These counterweights were parallelogram shaped, about 2-3 inches thick and weighed 80lb each. They had gripping holes at one end, but the hole edges were all at 90 degrees, making it painful to hold for any length of time.

It was well known around the yard that I was a lifter so I expected that sooner or later I would be asked to try to lift these up-to-then un-liftable weights. I ambled over and asked what they weighed. I already knew the answer. Someone asked if I could lift it. I said that I could lift two of them. There was a bit of disbelief at my proclamation. Now I had no choice, I had to give it a try. No one expected me to lift it since no one else had before me. But, I had been strict pressing about the same amount for reps so I figured I had a good chance. I also assumed the onlookers would be satisfied with any lifting of the weights. They were no technical experts, so if I was in trouble pressing them I would then try jerking them.

The counterweights were removed to the ground. I stood over them, just like I would over a heavy clean. I then went into a modified get-set position. I examined their shape and determined the best grip. Then I gave it a shot. The hardest part was in “cleaning” them. I suppose “continental-ing” would be more accurate. I grabbed hold of one in each hand and deadlifted them to my knees and then had to cheat curl them up to my chest. The hole handle edges dug into my hands and were quite uncomfortable. No one was too impressed with the shouldering. It was the press they wanted to see.

The counterweights were removed to the ground. I stood over them, just like I would over a heavy clean. I then went into a modified get-set position. I examined their shape and determined the best grip. Then I gave it a shot. The hardest part was in “cleaning” them. I suppose “continental-ing” would be more accurate. I grabbed hold of one in each hand and deadlifted them to my knees and then had to cheat curl them up to my chest. The hole handle edges dug into my hands and were quite uncomfortable. No one was too impressed with the shouldering. It was the press they wanted to see.

This was odd to me, since that was actually the easier part. The weights rested on my outer forearms while my hands were in the neutral position to press. And those grip holes dug into my hands. I set myself into a slight bow and with a bit of effort (remember, no warm-up) I did indeed press them out without too much effort. I pressed them straight up from my shoulders, since the locked-together kettlebell press technique was unknown then. That would have helped. I held the weights there for a while so that all could see and none could say I’d dropped them too soon. (These guys would have made good referees.) I was quite pleased to hear all of the “oohs” and “aahs.”

Later that day I added to my rep by throwing a nine-inch diameter by six-foot long tree trunk section – holding it up with my left hand and “shot-putting” it with my right hand onto the back of a truck. I could not have impressed them more if I had made a world record clean and jerk.

My glory did not end at quitting time though. In the evening I had repaired to the now late, lamented Highlander Tavern, beloved of University of Calgary students of the day. After suitable thirst quenching had been done it was time to deal with the consequences. I entered the room to “see Mrs. Murphy” but had not yet rounded the modest corner. I immediately heard a familiar voice describing my exploits of earlier that day to some unheard listener who was suitably impressed due to his own tractor familiarity. It was a fellow worker, still impressed with what he had seen and singing my praises Bosworth style. As I turned the corner he saw me and quite taken by surprised he shouted out, “That’s him! That’s him!” So I got a bit more time in the limelight and was prompted to shake hands with this new admirer, but being where we were I invoked the venerable gentleman’s right of refusal due to circumstances.

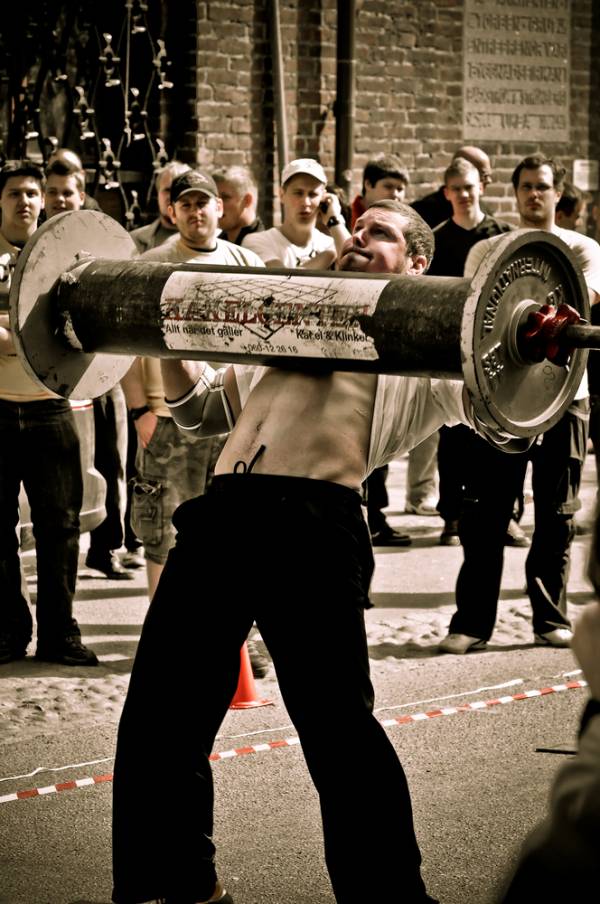

That feat was done long ago now, back in 1970. The lesson for lifters here, after describing what was little more than my own ego trip, is that there is a reason why strongman events are popular with audiences. This is because people can related to the feats. Competitors are grappling with objects that we have all struggled with, usually ones much smaller than those tried by the champs. An Olympic lift is beautiful to the cognoscenti, but difficult to appreciate by those who have never dreamed of moving an object in such a manner. It is a stylized expression of strength and power but the lifts themselves, especially the snatch seem to be little more than ‘tricks’ to most. This even includes those whose jobs involve a lot of strength themselves.

That feat was done long ago now, back in 1970. The lesson for lifters here, after describing what was little more than my own ego trip, is that there is a reason why strongman events are popular with audiences. This is because people can related to the feats. Competitors are grappling with objects that we have all struggled with, usually ones much smaller than those tried by the champs. An Olympic lift is beautiful to the cognoscenti, but difficult to appreciate by those who have never dreamed of moving an object in such a manner. It is a stylized expression of strength and power but the lifts themselves, especially the snatch seem to be little more than ‘tricks’ to most. This even includes those whose jobs involve a lot of strength themselves.

Final note: It also was mostly arm strength. If I had squatted a half ton I don’t think it would impress as much as my 160lb press.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.