The saying goes, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” This implies that if you say you mean to do something but then don’t do it, that’s just as bad as not even thinking about doing it in the first place. In other words, we get no “credit” for our intentions. How many times have you made a note to send a birthday card but not gotten around to it? Or had big plans to be productive over the weekend and then accomplished just a fraction of what you had on your to-do list? I suspect we’ve all been there, and we’ve all felt kind of bad depending on the nature of the unfulfilled intention.

But this adage puts the whole concept of intention in a negative light. In my experience, athletic and otherwise, intentions have played an incredibly important role in any progress I have made. Author Sonia Choquette discusses intention in her book Your Heart’s Desire: Instructions for Creating the Life You Really Want in a way that characterizes it as the powerful positive force it can be. She describes true intention in the following way: “Intention is not like wishful thinking, which is abstract, vague, passive, and diffused. Intention is like an arrow flying toward a target. Intention lays claim to your creative expression and establishes the foundation of your dreams.”

That description of intention gives it the gravitas it has demonstrated in my life, if used with the mindset implied in the description. Specifically, true intentions take time, effort, and ownership. I’m sure many of us would enjoy becoming a world champion or a highly paid professional in our sport of choice and have even daydreamed about what that would be like. But that doesn’t mean we intend to do so, Choquette-style. Just because we want something, it doesn’t automatically follow that we are willing to put the resources behind it in a way that makes it a true intention.

The key, I have found, is to pair intention with precise language and prioritization, as these put me squarely on the hook. One of my other favorite authors, Martha Beck, has a great way of explaining what I mean:

Suppose a friend asked you about the status of one of those unaccomplished to-do items from the weekend. Chances are you would say something like, “Yeah, I couldn’t get it done. I didn’t have time.” Or, if a friend invited you to an event you didn’t really want to go to, you would likely say, “I can’t. I’m too busy.” We all would. Well, Beck wouldn’t let us off that easily. She asserts the value of acknowledging the fact that often  when we say “I can’t,” we really mean “I won’t.” As she points out, we truly, honestly are able to do far more things than we are willing to admit. We can’t run 500 miles in one day, for instance, but we won’t refuse dessert. We can’t pick up a house and move it elsewhere, but we won’t make time to work out.

when we say “I can’t,” we really mean “I won’t.” As she points out, we truly, honestly are able to do far more things than we are willing to admit. We can’t run 500 miles in one day, for instance, but we won’t refuse dessert. We can’t pick up a house and move it elsewhere, but we won’t make time to work out.

For those of us who want to achieve athletically, it is a gift to be able to develop a clear understanding of what we cannot do and how that differs from what we will not do. It means the locus of control is internal, and while we may sometimes have to make difficult choices, the choices are ours to make. And our choices enable us to become clearer about what we truly intend and how that differs from what we vaguely think might be nice to have or do.

How does this play itself out in your athletic practice? Can you use the concept of taking responsibility for a “true intention” to help you make progress on an athletic goal that has been stagnating – or have you ever done so? Post your observations to comments.

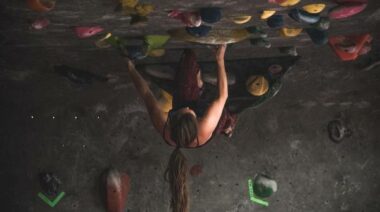

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.