The subject of doping in sports is both new and old, especially in weight sports. It is almost as old in the field events and North American-style football. Banned medications were once considered irrelevant in many other sports, but as we know, that is not the case today. Even the CrossFit Games is no stranger to this controversy.

The subject of doping in sports is both new and old, especially in weight sports. It is almost as old in the field events and North American-style football. Banned medications were once considered irrelevant in many other sports, but as we know, that is not the case today. Even the CrossFit Games is no stranger to this controversy.

Athletes have always looked for the edge that will allow them to get a jump on the opposition, at least until the opposition gets wind of the same thing. I’m almost certain if we were to go back to the days of the ancient Greek Olympics, you would find athletes swearing by a certain food or herb that they thought would give them a shot at the coveted laurel wreath. In World War II it was believed that Hitler’s armies indulged in testosterone and amphetamines to steamroll through Europe. Approaching modern times, we have had athletes who swear by their protein supplements and wheat germ oil.

But these appear to be primitive measures when compared to what would come out of the laboratories of the 1950s.

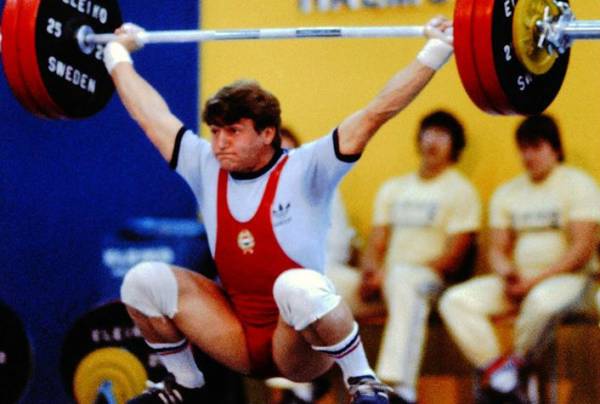

Olympic world-champion lifter Anatoly Khrapaty of the Soviet Union.

The Rise of Steroids

The stories of Dr. John Ziegler and his development of Dianabol in 1958 in order to compete with Russian athletes using testosterone are now legendary. Steroid doping in the United States and elsewhere can be said to have started at this time. It was also the beginning of the myths surrounding the use of such artificial testosterone.

Dr. Ziegler did his experiments with three top U.S. weightlifters, while at the same time experimenting with isometrics. The three lifters had fantastic results, which were publicly attributed to the use of isometrics, not those little blue pills. Thus began the commercial exploitation of isometric training, the effects of which can still be seen today. Walk into any gym and you will likely find one or more power racks. These did not exist before 1960 or so.

Inevitably, as all top secrets do, this secret became known. More and more people started training with isometrics and interest in those little blue pills increased. When people realized that most of the progress could be attributed to the pills, isometrics were the first victim. People simply assumed that this training method was rediscovered for the sole purpose of hiding the fact that steroids were the real secret. This is too bad, because isometrics are an effective way to increase absolute strength, although their use in Olympic weightlifting was misguided. But that is the subject of a whole ‘nother article, so I will leave this discussion here for now.

Isometric training faded away, but the doping continued.

A Miracle Drug?

The first myth about steroids was that they were some sort of miracle drug. People thought with the use of steroids you do not have to train nearly so much. Some even thought that you didn’t have to train at all. Just sit and pop these pills at regular intervals, and you too can become an Olympic champion. The fact that even world champions who were using the pills also had to train hard just to stay ahead of the opposition was forgotten. Even today, you hear stories of non-athletic high school kids taking the drugs and expecting to turn into some latter-day Adonis without having to work.

These drugs were invented to be a facilitator for training, not a substitute. The drugs allow the body to recover much faster, which in turn allows more intensive and extensive training than would be possible otherwise. In interviews, you still hear users try to deflect aspersions about their drug use with statements like, “No, I don’t use drugs. I just train awful hard.” The assumption here is that training hard and doping are mutually exclusive. In reality, they are mutually necessary.

Inevitably, the medical profession would offer up their comments. These drugs were first embraced by doctors for recovery from accidents and burns, but not for athletic purposes. Back then, medical professionals were even more ignorant of the requirements of sports than many are today. They simply did not expect people to use these drugs for anything other than as prescribed.

“Back then, we wanted to see what the human body could do without resorting to such extreme measures as training.”

Therefore, in order to discourage illicit use, the party line was that, “These substances will not improve athletic performance.” And according to the studies at the time, they were correct. This is because the experimentation was done on non-athletes with dosages so small that they would’ve been ineffective in any case.

But anecdotal evidence said otherwise. Everyone who took these drugs under proper conditions improved dramatically. Eventually people admitted that steroids did indeed work, but were bad for you. The side effects were also now becoming noticed anecdotally. It soon became the opinion of most that the use of anabolic steroids provided an unfair advantage and were even immoral. This led to some interesting comments by the powers that be. The best one, backed by the medical profession, was that, “Steroids were ineffective, but anyone using them was cheating.” The fact that both parts of this sentence are contradictory did not seem to occur to the speakers.

Public Perception

The general public, while now familiar with the idea that steroids made you stronger, still did not really subscribe to the idea that many sports would benefit from their illicit use. The idea persisted that it was only weightlifters and maybe throwers who would even consider their use. This dovetailed with the idea that people who train with weights were all a bit strange anyway. Lifters were not considered mainstream athletes, and some people still subscribed to the idea that real athletes do not use weights. Steroids were stigmatized, so their users should also be stigmatized.

As long as steroid use was confined to “those awful” weightlifters, nobody seemed to be too concerned about their use. No other athletes, especially the ones popular with the public, would do anything as stupid as to take drugs to improve their performance. Steroid use by football players was especially hushed up, as a successor to the 1950s myth that good football players would not train with weights.

The Canadian Controversy

Moving into the 1980s, I was around when the Canadian Weightlifting Federation had a series of positive steroid results. This eventually led to our loss of funding at the national level. We were then the bad boys and were shunned completely by other sports, which continued as before, albeit a little nervously. But inside the sport community, many suspected that the sawdust would hit the fan sooner or later.

Those with wider horizons would also suspect those awful foreigners, especially the ones behind the Iron Curtain. Our clean and honest Canadian and American competitors would certainly never do anything like that.

Both of these myths would explode at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. Such innocence disappeared forever in the aftermath of the 100m sprint final. Ben Johnson (CAN) beat Carl Lewis (USA) to win the gold, setting a new world record in the process. While the entire country of Canada celebrated this feat, weightlifters held back. For a day or so Johnson was the toast of Canada. But then the test results came out, and it was shown that he had been using stanozolol, a commonly used steroid.

This is when things got really interesting. After being caught, Johnson was stripped of his medals. Then the denials started. Johnson claimed his water bottle was tainted by some mysterious interloper in the dressing room. He even had many people believing him, until it was mentioned that his profile indicated long-term usage and he was forced to admit that he indeed used steroids. The Jamaican-born sprinter went from being the “Pride of Canada” to the “Shame of Jamaica” overnight. Thereafter he was always referred to in the media as “Jamaican-born runner Ben Johnson,” no longer as “Canadian runner Ben Johnson.”

1988 Olympic Games lifter Istvan Kerek of Hungary.

Immediately, the press went on a steroid hunt. The object of the game was not to find steroid users, but to find non-users in an effort to save some Canadian face. They interviewed our gold-medal boxer, future world champ Lennox Lewis. He had never used steroids. Good. Then they interviewed one of our synchronized swimming gold-medal winners, Carolyn Waldo. And you guessed it. She never used steroids, either. Whew! See, real Canadian athletes don’t use steroids.

Embarrassing as this all was for most Canadian sports fans, we weightlifters saw everything quite differently. This is because another myth was shattered. Life got a little bit better for us lifters after the Johnson debacle. Before it, drug use was limited to “those awful” weightlifters. After, it was a problem existing in all sports. Before Johnson, weightlifters were never given any slack when a positive drug test showed up. Suspensions occurred immediately. Johnson was given every consideration in the hope that he might prove his innocence. After Johnson, we were able to start our long journey back to some sort of respectability. We went from being worse than everyone else to being no better or worse than everyone else. In actuality, that was a big step upwards.

Pushing the Limits

I can’t help but mention that at one time, even training for a sport was considered “cheating.” Go back a century or so and you’ll see this idea, especially with regard to the distinction between amateurs and professionals. Contrary to what we see today, those who trained were considered professional, while those who did not were amateurs. Today, professionals train full time and amateurs cannot afford to.

Back then, we wanted to see what the human body could do without resorting to such extreme measures as training. If one athlete trained more or better than another, would he or she really perform better?

Now think of the word “training,” and replace it with “using.” You can see that the same argument exists today, albeit in a different form.

This discussion will continue in my next article. Now get back to the gym.

You’ll Also Enjoy:

- Drug Use in Sports: Can We Ignore It Any Longer?

- The Truth About Steroid Use in CrossFit: Don’t Ever Assume

- Once You’ve Used Steroids, Is It Possible to Ever Compete Clean Again?

- New on Breaking Muscle Right Now

Photos courtesy of Breaking Muscle/Bruce Klemens.