Many sports require extensive flexibility. Most scientific research focuses on using stretching programs to improve passive range of motion. In many sports, however, the active range of motion is at least as important as passive range of motion. The problem is active range of motion development is not as well understood. In a study this month in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, researchers investigated the best way to improve both active and passive flexibility.

Before I continue, let’s get the definitions straightened out. Many people confuse active and passive flexibility with dynamic and static flexibility.

Active stretching – This occurs when either the agonist or antagonist muscles are working during the stretch. You may have heard of PNF stretching, which is an active form of stretching where the antagonist muscle (the muscle being stretched) also contracts.

Passive stretching – In contrast, this when some other force engages the stretch. This is the sort of stretch that most people think of when they hear the word “stretching.” Either gravity provides the force or unrelated muscles help, such as when you do a standing hip flexor stretch.

Static stretching – This is when you hold the stretch in place. The intensity is usually measured by how long you hold the stretch.

Dynamic stretching – This is when you move into the stretch, and these are often counted in repetitions. To use a previous example, PNF stretching is not just active, it’s also static, because you hold the stretch while the muscles work.

Active flexibility often has a lower range of motion than passive flexibility. The reason is generally because many forms of active stretching rely on the agonist muscles to engage the stretch, and they become too weak at extreme ranges of motion to overcome the increasing tension of the muscles being stretched. This is not a problem in passive stretching. However, active flexibility may be required for many of the activities in your sport.

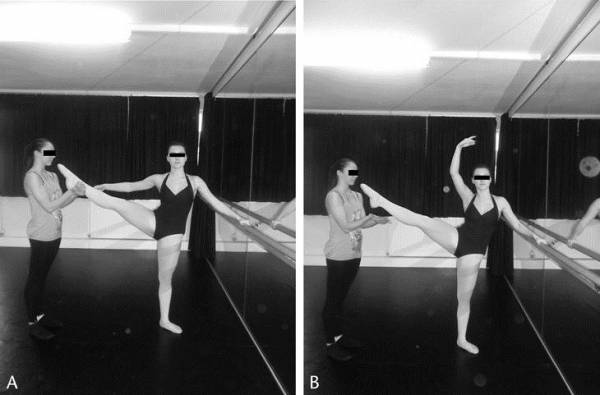

One major reason for this study is the lack of evidence showing how our stretching programs actually affect our sports performance. Take a recent article I wrote on hip flexibility as an example. The participants who engaged in a stretching program actually experienced reduced hip flexibility while running. In today’s study, the stretching programs focused on both traditional stretching as well as sport-specific stretching in a group of dancers.

The dancers were divided into one of three groups. There was a strength group that worked the agonist muscles on the tested stretches. The strength exercises focused on the hip flexors. There was also a low-intensity stretching group that performed static, passive stretches focusing on the hamstring, gluteal, quadricep, and calf muscles. Finally, there was a high-intensity group that did the same stretches as the low-intensity group, but stretched pretty hard, although not quite maximally. The researchers indicated that the latter method was used most frequently by the dancers before the study.

All three groups improved passive range of motion over the six-week period, with no significant difference between the groups. However, for active range of motion, both the strength training group and the low-intensity group outperformed the high-intensity group.

It’s possible that since high-intensity static stretching was the most common method before the study, the participants were already adapted to it. Nevertheless, this research seems to indicate that athletes of all types should begin incorporating more relaxed stretching methods and agonist-strengthening exercises for improved results.

References:

1. Matthew Wyon, et. al., “A Comparison of Strength and Stretch Interventions on Active and Passive Ranges of Movement in Dancers: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(11), 2013.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.