In any timed event the start is a critical component to the perfect race. This is especially true if we consider the start in any sprint event. A slow, or otherwise poor start can cost the win for an athlete.

While in sports such as track and field a slow start doesn’t necessarily affect how you recover as you continue to race, in swimming there is a dramatic change in element from air to water, and in a sprint event the start can make or break the outcome of the race.

In any timed event the start is a critical component to the perfect race. This is especially true if we consider the start in any sprint event. A slow, or otherwise poor start can cost the win for an athlete.

While in sports such as track and field a slow start doesn’t necessarily affect how you recover as you continue to race, in swimming there is a dramatic change in element from air to water, and in a sprint event the start can make or break the outcome of the race.

It was estimated by Cossor and Mason that at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games start times comprised 0.8% to 26.1% of the overall race time. This means that on average, for swimmers covering the 50m freestyle, the start accounted for a quarter of their race.

Although it looks like the swimmers are just throwing themselves from the blocks and gracefully falling in the water, the swimming start can be divided into four phases: block phase, flight phase, entry phase, and underwater phase. Understanding and seamlessly connecting each of these phases is the key to an elite level block start.

- Block Phase: The block phase can be also considered “reaction time.” It is the phase between the starting signal and the feet leaving the blocks, and the main focus of this article.

- Flight Phase: This is the phase between the feet leaving the block and the hands entering the water. It’s the air element of the dive before the beginning entering the aquatic realm.

- Entry Phase: This is the phase between the hands entering the water and the feet entering the water. In a sense, it is how the body slices the water. Entry angles will play a lot into the speed at which the swimmer not only enters the water but how he or she carries this speed/momentum into the next phase.

- Underwater phase: This phase is the duration the swimmer spends underwater. This phase has possibly been one of the most studied, definitely one of the most regulated, and likely one of the most crucial in a race as it is how the swimmer converts the speed he or she gets from the dive into the breakout, and carries it into the stroke. This will be a topic in a future article.

There are several variables in the block phase, the most important being a good stable setup on the block to allow for the most powerful take-off.

Blocks come in many varieties, high, low, tilted, with “fin,” etc. and it is very important for the swimmer to familiarize with the blocks before having to race. Most swimmers these days use a “track racing start” whether there is a fin on the block or not.

This seems to provide with the most power leaving the block, creating the best angle of entry in the water. Both feet should face forward with one foot standing behind the other.

The weight should be evenly distributed between the two legs in order to provide the most stability on the block. If the block has a fin, it I important to determine the most appropriate length and adjust the fin accordingly. You don’t want to have the feet too close, or too far apart, and ultimately the stature of the athlete determines the placement of the fin.

After the legs are placed on the block, the hands and arms positions are also important, and possibly the most overlooked.

The hands should grip the front of the block with all fingers and thumbs, giving the athlete a larger surface area on the block, ultimately translating into more force generated. The thumb can either wrap in front of the block or rest on top of the block, however more power is generated when the thumb is wrapped in front.

Most swimmers neglect to use their arms to dive into the pool and end up using them merely as counterbalance in the flight phase.

This is a wasted resource. If you have not yet tapped into your arms, it’s time to start (pun intended). The arms can help the propulsion on the dive by pulling backwards on the block and moving the athlete forward, especially when coordinated with an explosive takeoff from both front and back legs. We use two exercises in the gym that help create awareness of these two points:

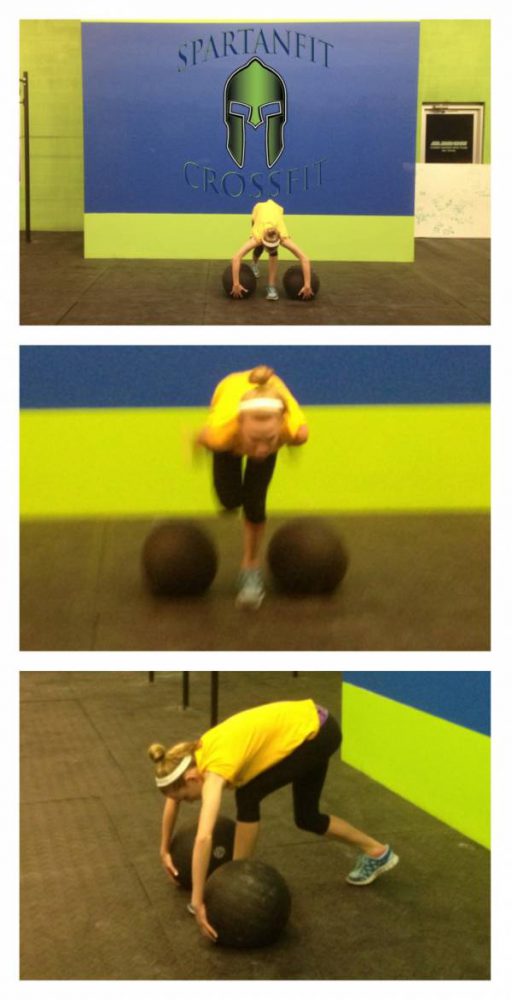

On the first one, we place the swimmer between two heavy D-balls (we typically use 150lb balls as these will provide the most resistance and little to no movement, just like the starting block). On command the swimmer takes their mark between the balls and emulates the start on the block.

In this drill we focus on the explosion from the starting position by coordinating pulling backwards on the D-balls with pushing the legs to move forward.

This drill greatly increases the swimmer’s awareness of the arms on the dive by adding the high level of resistance from the 150lb D-balls.

The second exercise we perform is tire starts. In these we connect a tire to a belt which is placed around the swimmer’s waist.

For added resistance, extra weight can be added to the tire (usually a 45lb plate does the trick). Like in the first exercise, the swimmer is commanded to take their mark and asked to start.

The resistance from the tire forces the swimmer to use extreme explosive power from the legs, which translates to an aggressive block phase and improved reaction times.

While swimming starts are not made in the gym, practicing drills like these increases awareness of the different components of the start and translate the explosion and speed onto the starting block.

Ultimately, you can practice these as much as you want, but the true test is to put your suit, cap, and goggles and test it out in the pool.