Recently, I tried to eat three whole chickens. Plus sides. Specifically, 3.5kg of schnitzel, complete with potato roesti, and sauerkraut (cabbage). For my American friends, that’s eight pounds of food, without leaving the table. In one sitting, in forty-five minutes.

I failed.

The food equivalent of a 600lb deadlift.

I left a little more than a kilo on the plate – that is, I only managed to eat about five pounds of food. Oh, the indignity of failure! This placed me second in a competition of seventy people. No one finished, and first wasn’t in front of me by much.

In an idle moment (and between bouts of indigestion that could have been used for riot control) I did a back-of-an-envelope calculation of the calories involved. Answer: over 6000. For a guy my size, that’s probably a hair over two entire day’s maintenance calories.

Now let’s leave aside the obvious questions like “Why?” (Answer: I have a serious problem with competitiveness) or “Is there something horribly wrong with you?” (Answer: Probably) and skip to the part that might actually be of use to you.

When you overeat at a semi-professional level, certain facts about food become clear that might not otherwise present themselves. This shouldn’t be surprising – people who frequently engage in any activity that pushes the limits of human endurance find enlightenment in the most unlikely of places. Why should eating as much as physically possible be any different?

A few obvious things happened, of course – I felt slightly ill, and didn’t eat much for two days afterwards. But here’s a few more surprising insights from my gluttony which can help you lose weight and control your perception of food in your life:

1) Remember the stomach is a big, dumb bag.

What decides when you’ve finished eating has almost nothing to do with the size of your stomach – unless you’ve had gastric bypass surgery, of course.

The first thing I noticed was an emotional reaction to the food that wasn’t normally there. That is, I was perfectly capable of putting more food inside me, but I really didn’t want to. I was shocked to discover, again and again, bite after bite that I could actually eat more. And more. And more still.

My emotional state seemed to be the king of this domain, and the actual space inside me remarkably accommodating. If you don’t value the integrity of your stomach and have nothing better to do, try it out sometime. It’s quite startling.

Diet Tip: The amount of food you eat has very little to do with how much you can physically consume. Visual, smell, taste, memory, social, and internal cues do the heavy lifting. Forget the phrase “I’m full,” it’s a product of circumstances. The amount of food you are around and how you perceive that food is a far better guide to how “hungry” you are than your stomach.

2) Your grandma was right. Your eyes are bigger than your stomach.

While I was eating my “challenge” meal, other people at the table were served normal meals – the kind I’ve always been happy with before. When they turned up, I turned away from my food for long enough to notice that they looked absolutely tiny, positively anaemic. Imagine that, a full-sized meal in a German restaurant that looks for all the world like an appetizer! What had changed?

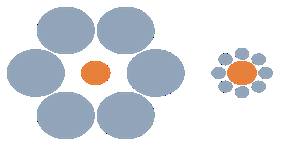

The best analogy I can come up with is the Ebbinghaus illusion:

Believe it or not, the yellow circles are precisely the same size, but the company they keep completely changes your perception of them. Take a ruler to your screen if you don’t believe me.

Believe it or not, the yellow circles are precisely the same size, but the company they keep completely changes your perception of them. Take a ruler to your screen if you don’t believe me.

Now, recognize that precisely the same relationship holds with food. Imagine that the blue circles form a plate, and the yellow circle is a meal. Trust me, it works! And not only is it blindingly apparent after your first kilo of schnitzel, there’s quite a lot of research on it.

Diet tip: Context makes a massive difference to how you perceive food. Do you buy big packets of raw food, in bulk? If you were trying to lose weight, I’d keep those packets actually out of the kitchen and cook from a smaller refillable packet in your cupboard. Do you have big restaurant sized dinner plates? Garage them. Get yourself some salad plates. A twelve-ounce steak actually looks rather impressive on an eight-inch plate.

3) Food cues make you “full.”

I’m very fond of schnitzel. You’d think that might make it easier to eat a lot of it, but it actually made it much, much harder. Almost immediately, I found I had to ignore every nice association I had ever had with this food. The light brown colour of good shallow frying? Ignored. The marvellous crunchy mouth-feel? Forget it. The smell of Jaeger sauce, the juniper and vinegar tang of sauerkraut? Gone.

All of these satiety cues – pieces of meaningful information that were telling my body I was eating – were unbelievably distracting. Towards the end, even overwhelming. Every sniff was torture, every pleasurable association was torture. The food had to be backfilled into my head, washed down with water, consumed as mechanically as possible.

I’ve watched a few bodybuilders prepare their food, and always been quite struck that they rarely try to make their food more interesting – no salt and pepper, herbs, spices, hot sauce, nothing. Hell, none of these even have any calories, so why would they make a difference? It isn’t because they don’t care about their food, as they often have pathological attention to detail when it comes to meal quantity and timing. The answer is clear now: because giving the food “character” would interfere with the ability to eat the amount that maintaining supra-physiological levels of muscle require.

Diet Tip: Don’t confuse character, or richness, or sensory experience with calories. The more sensory cues food has, the more satisfying it is. The opposite is also true – if you’re distracted from your food, it’s easier to eat more. So don’t distract yourself while you eat. So during dinner: no TV, no browsing the Intertubes, and no eating as fast as possible.

(And seeing as I’m feeling generous, here’s a one-time offer: if you email me at jamesheathers@gmail.com, I’ll send you my recipe for tomato consomme – simultaneously so ludicrously rich that over-eating it is almost impossible. And still fairly low calories, and still robustly healthy.)

I don’t try something like this often – in fact, it was a few months before I could even contemplate the idea of doing it again. Eating until you actually change shape is unbelievably uncomfortable without training. But, as I said before, in extremity lies insight. And so I suffer in order that we all might learn.

At least, that’s the excuse I’ll be using today. I might just be hungry.