A few years ago I came across an interesting paper on interval training. Given the popularity of interval training at this time, you might be thinking I’m a little late into the discussion. But what interested me about this particular research paper was what the authors discovered. After trying different interval protocols, it turned out some ratios made little difference to performance while others did have an impact. It would appear that training with some interval sets, despite working up a sweat, would make no difference at all to how well you performed!

I was then fascinated to see how many published interval-training regimens are based upon the ratios that made little difference and which chose the more successful ratios. I like interval training, particularly in the winter when I am inside on the trainer. Intervals provide a great way of keeping your attention on the session as you count off the minutes and seconds. Studies have also shown that appropriate intervals have a benefit on endurance. So, it is not always necessary to go for lengthy rides to work on your endurance.

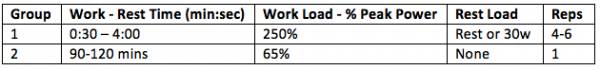

One research paper by Nigel Stepto and colleagues was written fourteen years ago in 1999, so interval training is hardly new. In this study, the cyclists performed sprint tests, measured peak power, and did a simulated 40km time trial before and after a 21-day training regimen. Test groups were allocated to different training regimens as shown in the table:

The peak power was measured in a ramp test with effort increasing every 150 seconds. Cyclists completed two days of base training and a third day of interval training. This pattern was repeated for twenty one days.

Now comes the really interesting bit:

- 40 km time trial speed: Significant improvements (2.5%) were found with intervals at 4 minutes and 85% of peak power. Thirty second intervals also increased this performance.

- Peak Power: Significant improvements were found with intervals at 4 minutes and 85% of the previous peak.

- Sprint Power: Did not seem to be significantly improved by any of the regimens tested.

This research made a real difference to my training. Having some evidence behind what I was doing added focus to what I was doing. A tool such as a power meter on a trainer or using the type of trainer that makes it possible to set the load makes this type of intervals training easy to incorporate.

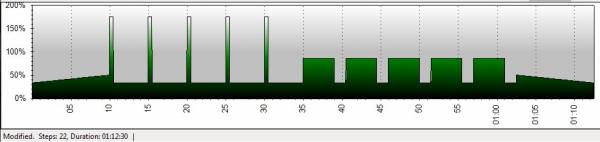

Here is an example of a mixed session of 30-second and 4-minute intervals, set up using the software PerfPRO Studio to run on a CompuTrainer. This makes a nice workout of one hour and twelve minutes, including warm up and cool down. The original study did not include a mixed session exactly like this, but from my own experience it does make an effective session. (Thanks to Nigel Stepto and his colleagues.)

The second paper that I wish to review is by Martin Gibala and colleagues. I included this to support my opening statements about endurance training. In this research they directly compared performance after a routine of short thirty second high intensity intervals (all out) with more traditional long endurance rides. The two groups were:

Each training session was followed by one to two days of recovery. This study took place over a fourteen-day period.

The conclusion of the study can be summed up in this one statement: “The major novel finding from the present study was that six sessions of either low volume SIT or traditional high volume ET induced similar improvements in muscle oxidative capacity, muscle buffering capacity and exercise performance.” Both groups improved their 30km simulated time trial times by between 7.5% and 10.1%. The short time trail results both improved by between 3.1% and 4.5% and power by approximately four percent.

I found all these results fascinating. While the topic of interval training is now well known, I was not aware until reading these that there could be a difference in results depending upon the work and rest times. Indeed, some of my previous training regimens might be considered a waste of time in terms of improving my performance. The level of improvement experienced by the test subjects, who were already at a reasonable level of fitness, over a short period of time is also impressive.

The number of variables in work-to-rest ratios and intensities could be expanded further, and I expect they will, as the search for optimizing training continues. The thirty second routines at either 175% or 250% are quite hard and it is perhaps not apparent sometimes how hard interval training needs to be. High Intensity does mean high intensity and you should be at an appropriate level of health to take part in them.

As winter starts to creep into the Northern Hemisphere and indoor training seems more comfortable, these two papers provide some good science behind choosing two interval training regimes of thirty seconds and four minutes both to improve endurance and race performance.

References:

1. Martin J. Gibala et al., “Short-term sprint interval versus traditional endurance training: similar initial adaptations in human skeletal muscle and exercise performance,” September 15, 2006 The Journal of Physiology, 575, 901-911.

2. Nigeel K. Stepto et al., “Effects of different interval-training programs on cycling time-trial performance,” Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise Volume 31(5) May 1999 pp 736-741