Back in 1999, research published in Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise spoke about the benefits of high intensity interval training to improve performance. The researchers found that some interval sessions worked better than others. (Click here for more on why a poor choice of work to rest ratios could actually lead to stagnating performance.)

In 2002, the same journal published more information by different researchers who looked at optimizing HIIT work-to-rest ratios – and came back with some impressive results. In the case of a 40km time trial, the average speed of study participants increased by five to six percent. That is about a three-minute difference on a 25-mile cycle course.

The 2002 Study

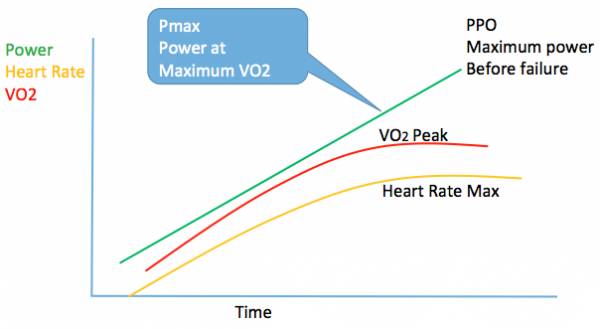

Rather than fixed work-to-rest ratios like in the 1999 study, the 2002 researchers let each athlete determine his or her own maximum threshold power from a ramp test. That is the power produced at maximum oxygen consumption (Pmax). Then, each athlete was asked to sustain that power for as long as possible to obtain an interval work duration (Tmax). This was then used as the basis of two study groups.

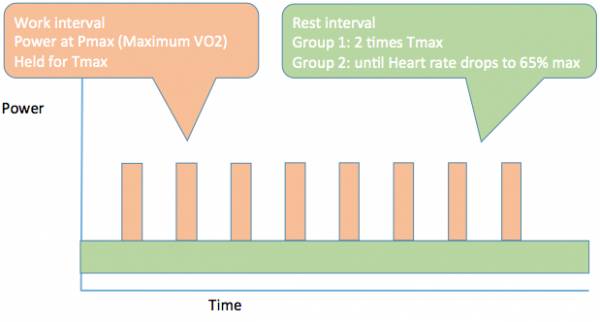

- Group one undertook eight intervals at Pmax for a time of Tmax with a rest period twice as long.

- Group two undertook eight intervals at Pmax for a time of Tmax with a rest period that extended until their heart rate had dropped to 65% of maximum.

Both groups increased performance significantly and more than the 1999 study protocol (thirty seconds with 4.5 minutes recovery), which was repeated in a third test group.

- VO2 peak increased to between 5-8%.

- 25-mile time trial speed increased to between 5-6%.

These impressive results were not obtained without a significant level of effort by the athletes concerned. In many cases, they were unable to complete the complete HIIT session. Sometimes only four or five of the eight intervals were completed, the athletes having become exhausted. This may not suit everyone as the test athletes were used to a level of training for some time prior to the study.

How to Do It

In addition to the HIIT workouts, the athletes performed low-intensity endurance sessions for two or three days between each one. This was the case for both studies.

If you wish to undertake this type of workout, you need to first find your Pmax and Tmax. To do this, you need a cycle trainer or cycle with some form of power measurement. Without access to expensive V02 measuring equipment, you can approximate the level of Pmax at the place where your heart rate starts to plateau on a ramp test. Ask a friend to monitor your heart rate as the power load is increased from 100 watts by fifteen watts every thirty seconds. Record the maximum power and your heart rate.

“The intensity of work was more important than completing the workout. If you are not able to perform this level of workout stress, HIIT may not be for you.”

After recovering, perform a test where you ride at the level of Pmax for as long as possible to obtain the value of Tmax. In the study, this varied from approximately from three to five minutes.

Your interval workout can now be designed.

The Takeaway

Both studies illustrate some important points.

- The level of work is extremely high and will be exhausting. The participants did not work a little bit hard. They worked extremely hard and often failed to complete the set. The intensity of work was more important than completing the workout. If you are not able to perform this level of workout stress, HIIT may not be for you.

- There were only two HIIT sessions in a week. The remainder of work was low intensity for the two or three days between each HIIT session. The combination of the two types of session gave the results, not one or the other.

- Some interval work-to-rest ratios work better than others. In the 1999 study, they used thirty-second intervals and four-minute intervals. In the 2002 study, intervals were based on measurements of each athlete’s response in a performance test (and were between three and five minutes).

- The studies used athletes who had been training for some time. They were still able to achieve significant improvements. If you have not been doing any training for some time, obtaining a good level of fitness first may be a more appropriate place to start.

You’ll Also Enjoy:

- Do Your Intervals Count? What Science Says About Work-to-Rest Ratios

- How to Choose the Proper Work and Rest Periods When Interval Training

- High-Intensity Workouts Help Less the Fitter You Are

- What’s New On Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Paul B. Laursen et al., “Interval training program optimization in highly trained endurance cyclists,” Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise, 2002.

2. Nigel K. Stepto et al., “Effects of different interval-training programs on cycling time-trial performance,” Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise Volume 31(5) May 1999 pp 736-741

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.