The word reify keeps popping into my head as I hear about the CrossFit versus NSCA lawsuit. Reify means “to make real.” In German, it is called Verdinglichung, which is literally, “making into a thing.”

I wonder whether this lawsuit reifies the idea that CrossFit creates injury. At the least, it creates a negative association for people not familiar with CrossFit.

Disclaimer: I have both NSCA and CrossFit certifications. I took the exam for the NSCA CSCS and participated in the CrossFit Level 1, gymnastics, and mobility certifications. I do not work for either company nor do I have a large stake in either. I paid money to become certified as a personal goal. I align myself with science, as I am a researcher and a professor. I hope to look at this debate from a scientific perspective.

Background Info

The lawsuit stems from an article written by graduate student Michael Smith and his mentor Steven Devor. They were at Ohio State University when they did this research. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, where the research was published, is operated by the NSCA. The NSCA creates certifications for trainers, such as the NSCA-CPT and the CSCS.

“Overall, the article is flattering to CrossFit. I imagine Michael Smith was interested in CrossFit and chose to use it as a platform for his dissertation study.”

CrossFit claims these certifications are competitors to their certification, and they state the article by Smith and Devor provides “false advertising.” But overall, the article is flattering to CrossFit. I imagine Michael Smith was interested in CrossFit and chose to use it as a platform for his dissertation study.

The Science of the Article

The researchers followed 54 participants for ten weeks as they completed CrossFit-style workouts. The participants were recruited from a CrossFit facility and continued their program there. The workouts are described in the article.

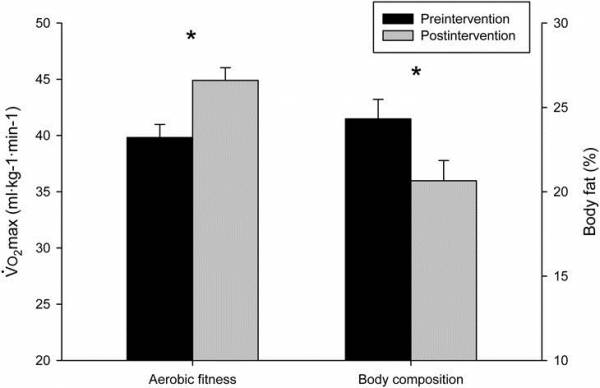

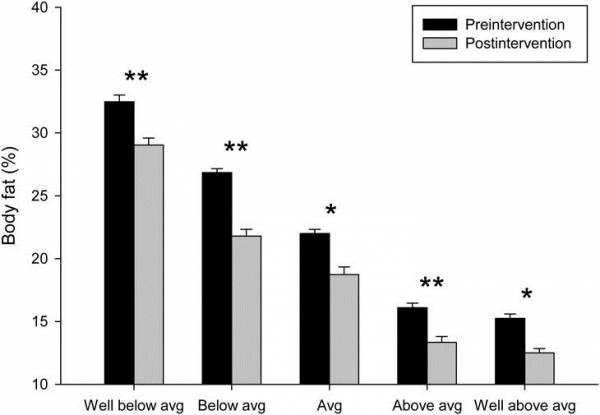

The 43 people who completed the program experienced significant reductions in body fat percentage and increased VO2 max. These people came into the study with different levels of experience, but the broad spectrum of individuals improved.

This study sounds like great marketing material. Even the title, Crossfit-Based High-Intensity Power Training Improves Maximal Aerobic Fitness and Body Composition, is a strong endorsement. But, in the discussion section, scientists have hemmed and hawed over the article. We are trained to describe what else might have caused the result and other limitations. Smith himself wrote about the sixteen people who dropped out of the study:

A unique concern with any high-intensity training program such as HIPT or other similar programs is the risk of overuse injury. Despite a deliberate periodization and supervision of our Crossfit-based training program by certified fitness professionals, a notable percentage of our subjects (16%) did not complete the training program and return for follow-up testing. Although peer-reviewed evidence of injury rates pertaining to high-intensity training programs is sparse, there are emerging reports of increased rates of musculoskeletal and metabolic injury in these programs (1). This may call into question the risk-benefit ratio for such extreme training programs, as the relatively small aerobic fitness and body composition improvements observed among individuals who are already considered to be “above average” and “well-above average” may not be worth the risk of injury and lost training time. Further work in this area is needed to explore how to best realize improvements to health without increasing risk above background levels associated with participation in any non–high intensity based fitness regimen.

I like this paragraph. It is what I ask my students to write. It gives enough ambiguity and says very little. A study of only 54 people can say little about injury rates. Imagine a small party of ten of your friends. You find three have the same birthday. You could assume that day has some special feature, but it is more likely to be a fluke. If you question 1,000 people and 300 have the same birthday, then you can say a lot more. Statistically, the second fluke is unlikely.

There is another controversial statement that seems to be the focus of CrossFit’s lawsuit:

Out of the original 54 participants, a total of 43 (23 men, 20 women) fully completed the training program and returned for follow-up testing. Of the 11 subjects who dropped out of the training program, 2 cited time concerns with the remaining 9 subjects (16% of total recruited subjects) citing overuse or injury for failing to complete the program and finish follow-up testing.

Russell Berger has indicated that he has proof that these nine participants did not have overuse or injury problems. He describes a phone call with the author’s mentor and with the CrossFit trainer at the facility. He also provided a video indicating a larger conspiracy against CrossFit from the NSCA. If a statement is not true, then the journal should retract it. So far, the journal stands by the authors’ statements.

Summary

Many of you probably read the article in question with preconceived ideas about CrossFit’s usefulness and its potential for injury. After reading the article, you could take either side. You could point out the good outcome as proof your notion was correct. You could take the injury rate and say CrossFit is injuring everyone. The truth is somewhere between these two views.

“The idea that we don’t know is central to this article and to science in general. Every study gives us a nugget of information that leads toward the next study.”

CrossFit has positive effects, as we see in this study. People also get injured doing CrossFit. What we don’t know is whether the injury rate is worse than in other sports. We also don’t know whether the positive effects are as good as other programs. The idea that we don’t know is central to this article and to science in general. Every study gives us a nugget of information that leads toward the next study. Over time and with many studies, we can find our answers.

If CrossFit is going to take aim at every single study that has a bad outcome, it could become a quixotic quest. There are bound to be other studies that show injury rates. Furthermore, the positive highlights of this study seem to be lost in the battle over injury rates.

The majority of this article is flattering to CrossFit. More focus on the positives would be helpful for CrossFit. It would avoid the association that comes from repeated exposure of CrossFit injury rates.

Further Reading:

- Preventing Common BJJ and CrossFit Injuries

- A Not-So-Scientific Look at Injury in CrossFit

- It’s Never About Rhabdo – It’s About CrossFit Hate

- What’s New on Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Berger, Russel. “NSCA ‘CrossFit Study.’” CrossFit Journal. Accessed March 30, 2015.

Martin, D. (n.d.). CrossFit’s Case Against the NSCA: The Facts.

2. Smith, Michael M., Allan J. Sommer, Brooke E. Starkoff, and Steven T. Devor. “Crossfit-Based High-Intensity Power Training Improves Maximal Aerobic Fitness and Body Composition:” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 27, no. 11 (November 2013): 3159–72. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318289e59f.

Photos are courtesy of Recon Photography.