When lifters gather around water coolers, in locker rooms, at bars, or wherever they have an opportunity to sit down and discuss the myriad aspects of their sport, they tend to speculate about the mysteries surrounding how to best progress. Many man-hours of time are devoted to this activity. Sometimes profitably, sometimes not.

One topic that garners a lot of discussion is the usefulness of added body weight. Nobody argues that more muscle always helps. Where the debate comes in is the usefulness of added fat.

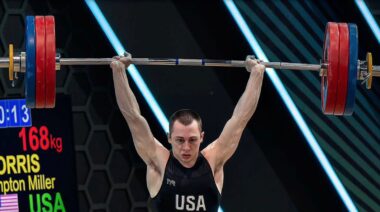

“[S]omeone will always point out how super heavyweights, whether in weightlifting or powerlifting, always seem to lift more and more as they get heavier.”

The Usefulness of Added Fat

While most would think added fat is of no use to the lifter, someone will always point out how super heavyweights, whether in weightlifting or powerlifting, always seem to lift more and more as they get heavier. (Remember, in the upper categories of both sports there is no bodyweight limit, so athletes who gain weight to get stronger have less inducement to control their fat accumulation.) So everyone starts wondering if there might be something to the idea that fat will help.

Mi-Ran Jang during the women’s +75kg event at the London 2012 Olympic Games

In truth, larger powerlifters can often squat more than they deadlift and superheavy weightlifters can recover from cleans more easily. It is also frequently noted that world record squats are less than the deadlift records in the lighter weight categories, but the opposite occurs among the super heavies. The 1000-pound squat was reached long before the 900-pound deadlift. So there may be something to being fatter and squatting more.

“Squat down a$$-to-grass and see if you get any lift off when you start your ascent. You’ll notice you do not get any.”

During these debates, someone inevitably will suggest that the large amount of abdominal fat on many super heavies gives them some sort of advantage. (It is interesting to note this observation is generally made by someone who has never been overweight.) The gist of the argument is that at the bottom of the squat the lifter can obtain an extra boost by having his belly bounce against his thighs at the bottom of the recovery. To many, this makes some sort of intuitive sense. And since most superheavy squatters have a certain amount of lower corpulence and do squat more than they deadlift, everybody shouts “Bingo!” These people then assume to have solved this little mystery. But is this theory true?

Fat Has No Elasticity

In order to answer this question, we need only go to our kitchen. Imagine a roast

with considerable fat on it, then cut that fat off the roast. Take this piece of fat and compress it, then release it. You’ll immediately notice there is no counterforce returning the fat back into its original shape. In short, fat has compressibility, but no elasticity. Put that fat in a baggie or some other way to encase it. You will still see the fat can be compressed but has no resiliency.

Super heavyweight Hossein Rezazadeh setting a clean and jerk world record

So it is with the squat. Get out of your kitchen and go to your gym (perhaps a healthier idea). If you’ve got any kind of spare tire, you can repeat the roast experiment with your squats. Squat down a$$-to-grass and see if you get any lift off when you start your ascent. You’ll notice you do not get any. Now go tell all of your skinny friends that fat bellies don’t make for big squats.

The Positive Effect of Intramuscular Fat

But does this end the benefits-of-fat discussion? Not usually. Invariably there will be somebody at the table who points out some examples of lifters who got fatter and stronger. Is this counterargument valid? It is certainly true this phenomenon is often encountered. But if fat has no elasticity, what causes this situation?

“[T]he intramuscular spaces have filled with fat, and as a result, the muscles are now attached to the bone at a different angle – a more advantageous one.”

This secret is related to the angle that force is applied to the skeletal structure. When a lifter gains adipose bodyweight much of it will settle in the subcutaneous parts of the body, often in the abdominal region. This is what shows up when a person noticeably gains weight. But fat will also gather between the muscle fibers. Your butcher will refer to this as marbling. It is highly desired by chefs because the little bits of fat between the muscle add that extra flavor in cooking.

Well, marbling is also advantageous for the lifter. The intramuscular fat cells produce what appears to be a larger muscle. The lifter notices that it produces a stronger muscle, as well. She may then conclude that the key to getting stronger is to get heavier, which means getting fatter. But what is really happening is that the intramuscular spaces have filled with fat, and as a result, the muscles are now attached to the bone at a different angle – a more advantageous one. This is especially noticeable in the pecs and the thighs.

An example of marbeling, where fat gathers in between the muscle fibers

The most efficient geometry of muscle attachment to bone is where the muscle is pulling perpendicular to the length of the ball, i.e., at ninety degrees. Angles of less than ninety degrees are less efficient. Forces there are lost in a trigonometric fashion. (Believe me, I don’t want to go into the math at this time). When the intramuscular spaces are increased with fat, the angle at which the muscles attach to the arms or legs becomes less acute, i.e. closer to the ninety-degree ideal and therefore more efficient.

This is what is generally happening with the superheavy powerlifters squatting more than they deadlift. Gaining a lot of new muscular body weight helps the bench and the squat more because those involve muscles that can take advantage of this situation more. Deadlifts do not engage the larger muscles in the same way. The erectors, the gripping muscles, and the muscles of the upper back take much of the load, but are not so amenable to the laying down of intramuscular fat.

“Get those muscles bigger not by filling in the intramuscular spaces with fat, but by getting the muscle fibers themselves larger.”

The Solution

So is the answer to upping your lifts porking up a little bit? It might be in the short term, but in long term there is a better solution. That solution is hypertrophy. (And of course that hypertrophy must be of the myofibrillar variety needed by most athletes, not the sarcoplasmic hypertrophy preferred by the bodybuilder.)

Get those muscles bigger not by filling in the intramuscular spaces with fat, but by getting the muscle fibers themselves larger. The muscle that is 100% muscle fiber is always going to be stronger than a similar size muscle that is eighty percent muscle and twenty percent fat.

Check out these related articles:

- How Much Overhead Are You Carrying?

- Weight Cutting In Sports: Is It Truly an Advantage?

- Size Does Matter – Managing Weight Cutting in Weightlifting

- What’s New on Breaking Muscle

Photo 1 “Korea_London_Jang_Miran_02” by Republic of Korea, Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

Photo 2 courtesy of Shutterstock.