Many people see the phrase “Krebs cycle” and their eyes gloss over and they skip to the next article. This article aims for limited glossy eyes.

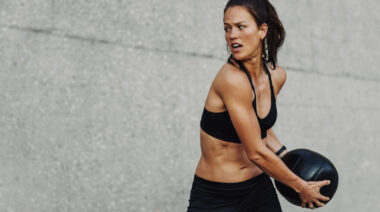

Today you will learn practical recommendations for optimal conditioning. This is not a conditioning program for those who want to run marathons. Rather, this is conditioning for those who care about being strong and functionally fit, and looking that way, too.

Many people see the phrase “Krebs cycle” and their eyes gloss over and they skip to the next article. This article aims for limited glossy eyes.

Today you will learn practical recommendations for optimal conditioning. This is not a conditioning program for those who want to run marathons. Rather, this is conditioning for those who care about being strong and functionally fit, and looking that way, too.

Some Caveats to Programming

Picking a name for a fitness program seems to be pretty important. As for prioritizing fitness, I align with StrongFirst‘s name in that strength comes first. It is more difficult to gain strength than it is to gain conditioning. Thus, most of a person’s efforts should be on building strength.

And I am not talking about a endurance sport conditioning. Rather, I am talking about Fred Hatfield’s challenge in his book Power of carrying twenty beer kegs up to a second floor pub.

Or even simpler, walking up a few flights of stairs or having sex without sounding like you’re having an asthma attack. We are talking about being functional.

Since everyone has individualized fitness and sports goals, their programs should consider those goals.

RELATED: Understanding the Differences in Individual Athletes

Andrew Read has written how running is the killer app of the body. Bramble and Lieberman describe hunter-gatherers as running their prey down to exhaustion. But recent papers indicate the theory does not hold.

I can’t imagine ancient tribespeople with glucose energy drinks along their trails. I would write an article on it, but frankly I am not passionate about running long distances.

“Your body does not know when it is going to stop, so it prepares for all possible outcomes.”

Running long distances is for people who want to run long distances. This article is about helping you build a base level of conditioning without diluting your strength goals. (Sorry, Andrew (and readers) to do a sloppy drive-by shooting on running long distances, but I need to get back to the topic.)

The Energy Systems

Early labels specified aerobic or anaerobic programs (with or without oxygen). Aerobic usually meant things like jogging and anaerobic meant lifting weights. We now talk with more nuances about the three energy systems.

- The alactic system is for the first thirty seconds of intense work.

- The glycolytic system takes over for the next minute and a half.

- When the others give up, the oxidative system takes over.

Nice idea, but it is not quite that simple. In truth, all systems function at the same time. Your body does not know when it is going to stop, so it prepares for all possible outcomes.

“In creating a general program, a person might want to train strength about 85% of the time and conditioning 15% of the time.”

We also have to consider rest periods. Let’s think about a basic exercise like kettlebell swings. Say we do for ten reps every minute on the minute. The first minute mostly uses the alactic system. But at the start of the second minute, our alactic system is only around 60% recharged.

Thus, we tap more into the glycolytic and oxidative systems in the second minute. At the start of the third minute, we are even more depleted in the alactic system (because we are depleting an already depleted system).

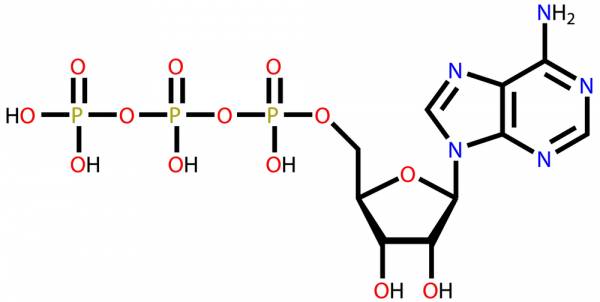

adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecule

The different energy systems all produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the currency of our energy.

Our muscles use the energy that comes from ATP and water shearing off one phosphate molecule. We are then left with adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and we need to turn it back into ATP to have more energy.

RELATED: ATP-PC, Glycolytic, and Oxidative, Oh My!

Each of the energy systems produces ATP in different ways. Watch this video for a more detailed explanation:

Alactic System

The alactic system is the simplest in that it produces ATP from ADP and a phosphate molecule donated by creatine phosphate. Because of its simplicity, it is a fast process.

RELATED: ATP Supplementation – Does It Work?

But our bodies have limited amounts of ATP and creatine phosphate. We run out quickly (creatine supplementation helps build limited reserves of creatine phosphate), and it takes about three to eight minutes for this system to replenish. (After 60 seconds approximately 80% of ATP is replenished; after 120 seconds 88%; after 180 seconds 93%).

Powerlifters will often wait a good amount of time between lifts to maximize this system.

- Power: Very high

- ATP Production: Very low

- Fuel Used: Stored ATP and creatine phosphate

Glycolytic System

Glycolysis uses glucose (or glycogen, stored glucose in the muscles) to produce ATP.

The full cycle produces more ATP than the alactic system. It takes more time because of its complexity. The first part of the cycle does not rely on oxygen to produce ATP and as it occurs early in the process it is quicker. The second part requires oxygen and it takes a bit more time. The video below provides more explanation:

- Power: High

- ATP Production: Low (Produces 4 ATP molecules, but 2 are used in the process)

- Fuel Used: Glucose and stored glycogen

Oxidative System

The oxidative system is the most complex as there are many different processes occurring.

We (optimally) create 36 molecules of ATP. But it is also a slow process, so it kicks in early when we start to exercise. Because we have historically equated this system with long-term endurance, it can seem unimportant. Watch the video for a great explanation of how this system works:

- Power: Low, because it is slow

- ATP Production: Very high (Produces up to 36 ATP molecules)

- Fuel Used: Glucose and stored glycogen, adipose and intramuscular fat

How to Get the Most Bang for Your Training Buck

It is likely that you should be training for strength first with more or less emphasis on conditioning (depending on your goals).

In creating a general program, a person might want to train strength about 85% of the time and conditioning 15% of the time. With only 15% of the time allowed, we must be efficient.

“Our goal is to build strength and to not take away from our gains, so more is not always better.”

Much of this idea comes from a new paper out of Peter Lemon’s lab on how they trained elite oarsman. Traditional rowing relies on a lot of endurance training with some strength training.

The researchers wanted to see the effects of reducing some endurance training and replacing it with sprint training.

RELATED: Sprinting 101

This approach did help their rowers with their 2,000-meter rows (a usual oxidative intensive task). Rest periods for the rowers were three to four minutes. (More similar to Burgomaster and Gibala’s research than to Tabata’s research, which used ten seconds of rest).

This paper as well as many others on Tabata-style research led me to focus my conditioning on doing only sprint type of workouts.

A Practical Program

- For 85% of your week, work on your primary strength activities.

- In one workout (maybe two), do sprint type training. (Read this earlier article for some ideas on what exercises to do). Our goal is to build strength and to not take away from our gains, so more is not always better.

- Over a four-week period, start with three- to four-minute rest periods and then move to shorter one- to two-minute rest periods. This changing of the rest periods will place more emphasis on different energy systems. It is not a bad idea to cycle up and down with rest periods (and maybe once in a while do a Tabata workout with short rest).

- The most important feature of these workouts is the all-out effort. We want to incorporate all energy systems working in concert with each other.

References

1. Bramble, Dennis M., and Daniel E. Lieberman. 2004. “Endurance Running and the Evolution of Homo.” Nature 432 (7015): 345–52. doi:10.1038/nature03052.

2. Burgomaster, Kirsten A., Krista R. Howarth, Stuart M. Phillips, Mark Rakobowchuk, Maureen J. MacDonald, Sean L. McGee, and Martin J. Gibala. 2008. “Similar Metabolic Adaptations during Exercise after Low Volume Sprint Interval and Traditional Endurance Training in Humans.” The Journal of Physiology 586 (1): 151–60.

3. Hatfield, Frederick C. 1989. Power: A Scientific Approach. 1 edition. Chicago: McGraw-Hill.

Pickering, Travis Rayne, and Henry T. Bunn. 2007. “The Endurance Running Hypothesis and Hunting and Scavenging in Savanna-Woodlands.” Journal of Human Evolution 53 (4): 434–38. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.01.012.

4. Stevens, Alexander W.J., Terry T. Olver, and Peter W.R. Lemon. 2015. “Incorporating Sprint Training With Endurance Training Improves Anaerobic Capacity and 2,000-M Erg Performance in Trained Oarsmen:” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 29 (1): 22–28. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000593.

Photos courtesy of CrossFit Empirical.