Movement doesn’t come naturally to some people. The modern environment has selected against it. Our genes were forged out of suffering and expect hardship.

This means that deep down our DNA is constantly telling us to save our energy for the day there are no more pizza delivery guys, and we need to go hunt a pizza down ourselves. But barring a zombie apocalypse, this probably isn’t going to happen.

Movement doesn’t come naturally to some people. The modern environment has selected against it. Our genes were forged out of suffering and expect hardship.

This means that deep down our DNA is constantly telling us to save our energy for the day there are no more pizza delivery guys, and we need to go hunt a pizza down ourselves. But barring a zombie apocalypse, this probably isn’t going to happen.

“We just want to keep moving for decades to come, not get type 2 diabetes, and then not die of pneumonia after falling and breaking a hip at 85.”

We know that movement can have a huge, positive impact on health. Despite this, the current guidelines that tell people to “move more” have made no difference to our chronic disease rates.1So what should we do instead?

As ever, I look to science. I love science. Admittedly, there’s a huge amount of rubbish out there in the world of research. However, I think some core overall principles are emerging that suggest how we can kick ass for as long as possible.

It’s About Quality and Longevity of Life

If you’re more of a “prepare for the zombie apocalypse” kind of person, this probably won’t be quite your speed. Equally, if you love the feeling of testing the limits of your body and mind under a barbell, over an obstacle course, or along hundreds of miles of endurance racing, please don’t let me stop you.

For the rest of us, the number of marathons we haven’t run or the size of our snatch doesn’t really matter that much. We just want to keep moving for decades to come, not get type 2 diabetes, and then not die of pneumonia after falling and breaking a hip at 85. This quality of life is easier than you think.

As everybody loves a pyramid, let me introduce you to mine.

The Great Upside-Down Movement Pyramid

Maybe the name needs some work. But it definitely works better upside down.

The Base: Sit Less

The reason this forms the base is because no matter how much you exercise, most of the benefit is lost if you spend the rest of the day sitting. There’s some interesting research behind why this is the case (inflammation, insulin resistance, etc.), but the key point is that this finding has been replicated a number of times.2

“As the amount of time spent sitting every day goes above seven to eight hours, your risk of death increases, regardless of how much exercise you do.”

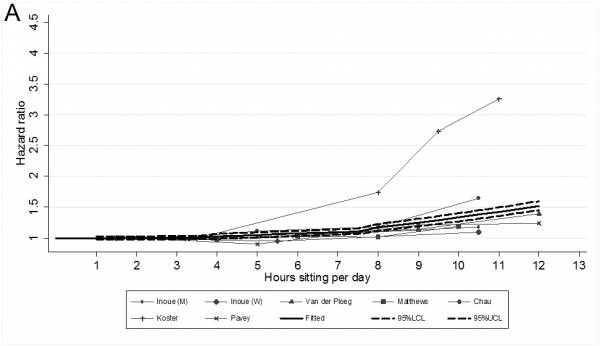

Just look at this graph from a recent meta-analysis (study of many studies).3The different lines are from different studies, so focus on the average – the thick black line. As the amount of time spent sitting every day goes above seven to eight hours, your risk of death increases, regardless of how much exercise you do. Bugger.

Graph shows hazard ratio (HR) for death from any cause, adjusted for activity level. Baseline HR is 1, so an HR of 1.5 (i.e. 12 hours of sitting per day) indicates a fifty percent increase in overall risk in death.3

The Next Bit: Walk More

This is the boring bit that everybody skips. But brisk walking (imagine walking as if you’re late for work) is the best-studied form of exercise, with the broadest range of benefits. It is also the basis of the most common activity guideline of 150 minutes of physical activity per week.

The equivalent of fifteen minutes brisk walking to and from work, or half an hour during lunchtime, can halve the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease, and potentially cancer. 4-6 The health and weight loss improvements seen with increased walking seem to far outweigh the rather paltry amount of calories it burns. Magic.

“[I]t probably doesn’t matter too much what you do. Lift weights. Swing kettlebells. Do yoga. Do bodyweight movements in the park. Climb a tree. Give your kids a piggyback.”

Then: Move Stuff

In scientific research, this is usually called “resistance training”, and often happens on weight machines in the gym. However, doing any kind of resistance training appears to be hugely beneficial for long-term health.

The protocols studies use vary quite widely, which suggests that it probably doesn’t matter too much what you do. Lift weights. Swing kettlebells. Do yoga. Do bodyweight movements in the park. Climb a tree. Give your kids a piggyback. All of this counts, because it can increase strength in every plane of movement.

Resistance training is safe and improves outcomes in every disease it has been tested in, from stroke to heart failure to cancer. Lifting weights is also the best way to keep your waistline under control.7 And stronger people really are harder to kill.8,9

Then: Move Really Quickly

Improving your cardiovascular fitness (often measured as your ability to use oxygen, or VO2) is one of the best ways to reduce your risk of death and chronic disease. A number of studies have shown that a few maximum-intensity sprints of 10-30 seconds for a total of around twenty minutes (including rest periods and warm-up time) can improve VO2 max as least as well as moderate intensity cardio lasting 45 minutes to an hour.10-13

“Improving your cardiovascular fitness… is one of the best ways to reduce your risk of death and chronic disease.”

If you already have some kind of chronic disease and are trying to improve your fitness, interval sprints are almost twice as good as traditional cardio.14 More fitness in half the time? Gimme.

(Bear in mind that it’s easy to overcomplicate sprinting, which risks injury. I would suggest stationary bike, rowing, or running sprints, which is what most studies have used.)

Finally: Move for a Long Period of Time

I’m a big fan of more traditional endurance training, but most of the benefits of this type of training can be gained from the levels above. For instance, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise dramatically boosts aerobic fitness and improves immune function.15,16However, if you’re doing your brisk walking and sprinting, you’ve got these covered already.

Importantly, when it comes to running, more isn’t necessarily better. Diminishing returns and adverse effects are seen above sixty minutes of endurance exercise per day for long periods of time.17

As the cherry on your movement cake, longer cardio training sessions (cycling, running, etc.) are a great chance to get out of the city or train with friends. Both of these factors can have a wide array of benefits on health and longevity,18-20 because when it comes to life, some things are much more important than exercise.

Summary: How to Use the Pyramid

- Make movement a habit rather than a chore.

- If you’re not managing to do the level above, don’t do the level below.

- As you use more levels of the pyramid, it becomes increasingly unstable. This means you need more time to recover – eat, sleep, rest.

- If you can’t recover better, don’t add more.

- Don’t obsess over the details. Do what comes naturally and what you enjoy.

Combinations: Though they haven’t often been studied in a systematic way, things like fight training (boxing, martial arts, etc.) and CrossFit will often cover everything, from strength and interval training to endurance. However, if the coach at your CrossFit box has you doing soul-crushing thirty-minute metcons (metabolic conditioning workouts) every day, consider introducing him or her to the pyramid.

Disclaimer: If you have some kind of chronic disease, you should discuss various exercise regimens with your doctor. Movement can be better than medications and medical treatments, with fewer potential side effects. Some of the references here are a good place to start, including.21

Take a look at these related articles:

- In 2015: Move Better Than You Ever Have Before

- Walking: The Most Underrated Movement of the 21st Century

- Use Play to Become Fitter and Stronger for Longer

- What’s New on Breaking Muscle UK Today

References:

1. Haskell WL et al., “Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association“. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Aug;39(8):1423-34.

2. Biswas A et al., “Sedentary Time and Its Association With Risk for Disease Incidence, Mortality, and Hospitalization in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Ann Intern Med. 2015 Jan 20;162(2):123-32.

3. Chau JY et al., “Daily sitting time and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis.” PLoS One. 2013 Nov 13;8(11):e80000.

4. Hamer M and Chida Y. “Walking and primary prevention: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.” Br J Sports Med. 2008 Apr;42(4):238-43.

5. Richardson CR et al., “A meta-analysis of pedometer-based walking interventions and weight loss.” Ann Fam Med. 2008 Jan-Feb;6(1):69-77.

6. Newton RU and Galvão DA. “Exercise in prevention and management of cancer.” Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008 Jun;9(2-3):135-46.

7. Mekary RA et al., “Weight training, aerobic physical activities, and long-term waist circumference change in men.” Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015 Feb;23(2):461-7.

8. Ruiz JR et al., “Muscular strength and adiposity as predictors of adulthood cancer mortality in men.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 May;18(5):1468-76.

9. Lee JJ et al., “Global muscle strength but not grip strength predicts mortality and length of stay in a general population in a surgical intensive care unit.” Phys Ther. 2012 Dec;92(12):1546-55.

10. Metcalfe RS et al., “Towards the minimal amount of exercise for improving metabolic health: beneficial effects of reduced-exertion high-intensity interval training.” Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012 Jul;112(7):2767-75.

11. Helgerud J et al., “Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve VO2 max more than moderate training.” Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Apr;39(4):665-71.

12. Moholdt T et al., “The higher the better? Interval training intensity in coronary heart disease.” J Sci Med Sport. 2014 Sep;17(5):506-10.

13. Tabata I et al., “Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2 max.” Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996 Oct;28(10):1327-30.

14. Weston KS et al., “High-intensity interval training in patients with lifestyle-induced cardiometabolic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Br J Sports Med. 2014 Aug;48(16):1227-34.

15. Matthews CE et al., “Moderate to vigorous physical activity and risk of upper-respiratory tract infection.” Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002 Aug;34(8):1242-8.

16. Nieman DC et al., “Upper respiratory tract infection is reduced in physically fit and active adults.” Br J Sports Med. 2011 Sep;45(12):987-92.

17. O’Keefe JH et al. “Potential adverse cardiovascular effects from excessive endurance exercise“. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Jun;87(6):587-95.

18. Haluza D et al., “Green perspectives for public health: a narrative review on the physiological effects of experiencing outdoor nature.” Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014 May 19;11(5):5445-61.

19. Cohen EE et al., “Rowers’ high: behavioural synchrony is correlated with elevated pain thresholds.” Biol Lett. 2010 Feb 23;6(1):106-8.

20. Thøgersen-Ntoumani C et al., “Changes in work affect in response to lunchtime walking in previously physically inactive employees: A randomized trial.” Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015 Jan 6.

21. Walther C et al., “Regular exercise training compared with percutaneous intervention leads to a reduction of inflammatory markers and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease.” Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008 Feb;15(1):107-12.

Photos courtesy ofShutterstock.