Our breath is our primary nutrition. We can go without food for somewhere in the range of twenty to forty days, and we can go without water for a significantly shorter period of time at about three to seven days. However we can go without breath, or oxygen, for only three to seven minutes. Try to hold your breath and eventually your nervous system will shut the experiment down by making you black out so it can get some air into you again.

Our breath is our primary nutrition. We can go without food for somewhere in the range of twenty to forty days, and we can go without water for a significantly shorter period of time at about three to seven days. However we can go without breath, or oxygen, for only three to seven minutes. Try to hold your breath and eventually your nervous system will shut the experiment down by making you black out so it can get some air into you again.

That we need oxygen is clearly well established (duh). But what we talk about less is when people are restricted in the full expression of their breath due to structural compensations, and therefore are receiving sub-optimal cellular nutrition. Are you going to black out or get brain damage from this kind of low-level restriction? Nah. But as an athlete if you have some kinks in your breathing you will be slower to recover and to heal, and you will at some level have subpar performance (i.e. if you pay a little attention to training your breath you are likely to feel like you’ve been given some super-powered training mojo).

There are two main ways that people develop breath restrictions they may not notice:

- They decide, either consciously or unconsciously that there is such a thing as “good” breath and “bad” breath.

- Their abs of steel start getting in their way.

Good Breath vs. Bad Breath

First, we have three main kinds of breath – clavicular, thoracic, and abdominal:

Clavicular breath happens up high by your collarbone and first ribs. It lifts your shoulders up rapidly and dramatically to get as much air in as possible. This is emergency respiration and you may notice it comes in handy when you are at the end of a race (people leaning forward with their hands on their thighs panting furiously are engaging in clavicular breath), or when you need to move quickly in an emergency (people who sprint to the road to get their child out of traffic are also engaging in clavicular breath). In both of these cases, your nervous system decided that you needed to get as much air as possible and pronto. This gets the job done without the blacking out.

Thoracic breath happens where your lungs are, i.e. everywhere you have ribs. Thoracic breath happens most naturally when standing or sitting, as you need your core and pelvic floor to be more “on” in these positions to support your upright spine. If you force extreme belly breath while sitting or standing you are creating a kind of plunger effect on your pelvic floor, which may be ultimately good for the adult diaper industry, but probably isn’t great for your long-term quality of life.

Abdominal breath, sometimes called belly breath, occurs most naturally when we are lying down or at rest. This is when, because of the position of your body, the full expression of your respiratory diaphragm descending and moving the organs downwards can occur. This is a very relaxing breath for the nervous system, unlike its buddy clavicular breath.

Of course none of these types of breathing occur in isolation, so it’s more a matter of which you are doing most at any given time. You may also notice that none of these kinds of breath are bad. It’s just that some are more appropriate to certain circumstances than others. Trying to fall asleep while doing rapid, shallow clavicular breath won’t really do you any favors in the insomnia department, and belly breathing while you sprint to grab your child out of traffic won’t do you or your child any favors (as you will pass out before you get there from not having enough oxygen to get the job done).

Sometimes we choose a “good” breath and a “bad” breath and convince ourselves that we should only be breathing one way and commit to it. This can happen consciously if you had a teacher who at some point told you there was a holy grail of breath. This can happen unconsciously if you have restrictions in your soft tissue from injury, movement patterning, or trauma of both the emotional and physical variety.

In reality, what we want is to have the ability to breath in all ways and in all dimensions, and then leave the day-to-day decision making up to our nervous systems. I am by no means advocating against using certain kinds of breath for training – whether it’s the more bracing breath of powerlifting or the breath explorations, called pranayama, of yoga – but we should not have to think about our breath most of the time. We should just be fluent and adaptable and let our nervous system choose what is going to be most helpful.

When Good Abs Go Bad

Now on to the abs of steel issue. Whether it’s the six-pack, shredded up, wearing the cobra hood up at all times kind of abs, or the perma-corset abs that are advocated by some forms of Pilates and dance, constantly splinting like this can cause trouble. Our core – meaning the hard and soft tissues of our abdomen, spine, and pelvic floor – should not be like wearing a rigid metal back brace on the inside of our skin.

Our core is the center of our structure and has so much gorgeous movement potential, and with good reason. The core is really meant to function like a movement conduit, translating input across our center and into our limbs and upper and lower body. To shut it down rigidly shuts down a lot of potential, including our breath.

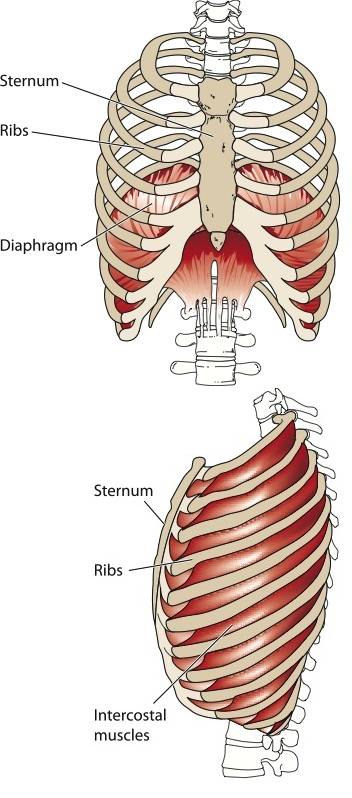

Meet Your Respiratory Diaphragm

While breath is complex, for the purposes of adding a little breath training into your work at home, let’s work on freeing up the capacity of the respiratory diaphragm. The respiratory diaphragm can kind of be seen as the mob boss of breath, if you will. It says what goes first, and everything else follows.

Since your respiratory diaphragm can’t be trained the way, say, your biceps can (though I would love to see someone make a video Respiratory Diaphragms of Steel), it becomes less about making it “stronger” and more about making it responsive and allowing all of the other tissues it affects to react to its movement. We need core musculature that is strong and mobile.

You can picture the diaphragm muscle as an umbrella that lives, dome-shaped, high up under your ribs. It’s a pretty fascinating muscle because while it originates by lining the inner surface of the lower six ribs, and also attaches at the upper two or three lumbar vertebrae and the inner part of the xiphoid process on the sternum. Its insertion is a little wacky because it is on itself, via the central tendon (the handle of the umbrella for visual purposes, though it does not function at all like the handle of an umbrella). All breath occurs by a change in internal pressure, and this change is produced when the central tendon pulls down, increasing the volume of the thoracic cavity, which pulls air into the lungs and displaces the organs downwards (this is the belly swell of abdominal breath).

So, watch the video below and let’s give your diaphragm some love via soft tissue work with a Coregeous ball. This is from the Yoga Tune Up world, and the Coregeous ball is an air-filled, super gushy, slightly sticky ball. Perfect and delish for doing home core tissue work. Do not do any work in your abdomen with any ball that is harder than this – no lacrosse balls, therapy balls, etc. And while the ball should be air-filled, it should be pliable and air-filled, so no basketballs or soccer balls! Be kind to your abdomen, okay? Last caveat – this work is a no-no for anyone with a hernia or a diastasis.

Photos 1-3 courtesy of Shutterstock.