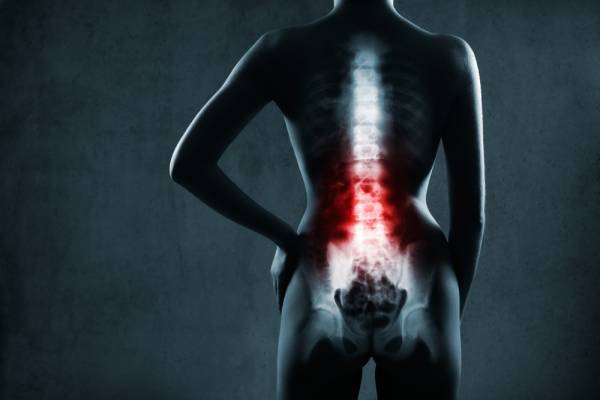

If you’ve ever suffered a back injury, gone to a Pilates class, or worked with a fitness coach who tried to help you activate your core, then you’ve heard it already. The infamous “draw your belly button to your spine” cue.

Touted as a way to improve your core stability this technique, known as abdominal hollowing, has been a universally accepted, go-to exercise for physical therapists (PTs) and fitness coaches for the last decade. In fact, following any sort of low back injury, abdominal hollowing is usually the number one exercise physical therapists teach clients during rehabilitation. The therapists themselves are taught the technique in school, and it has been long accepted as the standard exercise for spinal stability.

But let me ask you something: just because something has always been done a certain way, does that make it the best way?

Some exercises become universal, but not because they are great, or even effective. People fall into a trap of teaching and doing what was taught to them. They rarely pause to question the movement, the anatomy, or the biomechanics. And this is exactly why abdominal hollowing has been taught all of these years.

Even with that being said, however, exactly how the entire PT community bought into this technique is beyond me. Unfortunately, not only is there a complete lack of evidence to support its use, but it has also been shown that the technique in no way leads to a stable spine. In fact, abdominal hollowing does precisely the opposite and effectively ruins our spinal stability.

So, why was it ever thought to be a good idea?

The Background

The abdominal hollowing technique comes from a group of Australian researchers, including physiotherapist Paul Hodges, who published a study in 1999 that indicated that in healthy individuals the deep muscles of the core – specifically the transversus abdominis (TrA) – would activate a fraction of a second before any movement was performed.3 In other words, before participants would perform a movement, their TrA would fire.

When they tested individuals with low back pain, however, they found the TrA had a delayed reaction. This lead to trying to isolate the TrA in order to fix the altered motor pattern, and here is where abdominal hollowing was born.

The technique was meant to engage the deeper core muscles, including the TrA and multifidis, without causing the more superficial abdominal muscles (internal and external obliques and rectus abdominis) to contract. The problem with this is that focusing on single muscles actually creates dysfunction in spines and is highly problematic.

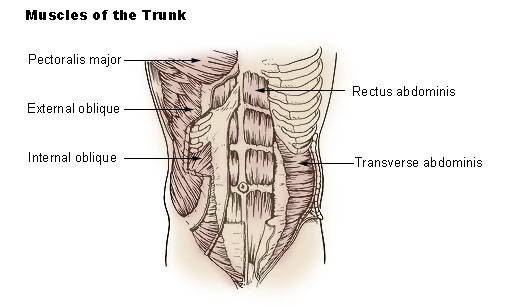

Let’s Review Some Anatomy

Speaking very basically, we have three layers of abdominal muscles. The outer layer is our rectus abdominis (think six-pack muscle), which runs vertically from our ribcage to our pelvis. In the middle, we have our external and internal obliques, which run diagonally from our lower ribcage to our pelvis. And finally we have the TrA, which runs horizontally beneath the other layers.

This little anatomy review will prove helpful as I go though abdominal hollowing and bracing a bit more.

Back to Abdominal Hollowing

Though it is true that studies have shown there are perturbed motor patterns in the TrA in individuals with back pain, more recent studies have shown that perturbed patterns of activation are actually found in virtually all muscles in those with back pain.4,5 You see, our muscles work as teams to not only create joint torque, but to also (and more importantly) maintain core stability. There is no single muscle responsible for this.

So instead of training muscles as a team and as they function in real life, hollowing aims to instead activate a single muscle in isolation. Now, research does show that hollowing will in fact produce increased activity in the TrA, but at what cost? Yes, you are getting a greater TrA activation, but you are also causing a weakening of the external and internal oblique muscles, as they must essentially be inactive in order for hollowing to occur. This actually leads to a less stable spine, meaning a greater chance of injury – the exact opposite effect from what we want.

Enter Abdominal Bracing

Think about what you would do if you were to prepare yourself for someone to punch you in the gut. You would immediately tense and stiffen you core to brace for the impact. This is exactly what abdominal bracing is, a term first coined by Dr. Stuart McGill of Canada, a leading expert in spine mechanics.

In abdominal bracing, you are simultaneously co-activating all layers of core muscles (remember the anatomy lesson?), in addition to activating your lats, quadratus lumborum, and back extensors. This means the entire abdominal wall is activated from all angles, sides, and directions, causing the three layers of the muscles to actually physically bind together.

This binding enhances the stiffness and stability of the core to a much greater degree than what would otherwise be produced by the sum of each individual part. This is what McGill refers to as superstiffness. It is this stiffness that provides us with 360 degrees of spinal stability, making us injury resilient and helping us achieve optimal performance.

You see, stiffness is actually key for spinal stability and spine health. Having a stiff core eliminates micro-movements in the joints that lead to spine and tissue degeneration. Without stiffness, these micro-movements would gradually gnaw away on our nerves, eventually causing pain and even disability. Stiffness braces these micro-movements and takes away the pain, essentially building a spinal armor.

To visualize this a bit better, McGill gives the great example of a guy-wire system (like a ship mast). Think of the obliques and the rectus abdominis as the supporting guy wires of the spine. They will be more effective at stabilizing the spine when the have a wider base, as they do when the core is braced. On the other hand, when the abdomen is drawn in, or hollowed, there is a much narrower base of support leading to significantly less stability.

Are Bracing and Hollowing Mutually Exclusive?

Some therapists and coaches will argue that abdominal bracing and hollowing do not need to be mutually exclusive exercises. They say each technique is good and their use depends on what you’re doing. For example, I’ve spoken to therapists who say abdominal hollowing is ideal for a Pilates class, during a physiotherapy session, or during day-to-day tasks, while bracing is ideal for more complex movements such as lifting weights.

This is flawed thinking. Why would we teach our body two completely different motor patterns? If we teach abdominal hollowing for everyday tasks, we are essentially encouraging our rectus abdominis and oblique muscles to weaken and remain inactive. Furthermore, we are not allowing our core to maintain its stiffness, which means one unexpected bump, fall, or movement and we could be dealing with a significant back injury. Our bodies do not work in isolation, and we should not be training them as if they do.

In Conclusion

When it comes to spinal stability all of our muscles work together and play an important role. These muscles must be balanced in order to be able to withstand large loads placed upon them to keep us injury free. Training single muscles leads to the exact opposite effect, instead causing an unstable, injury prone spine. This is why when training core stability, whether immediately following an injury or during athletic performance training, we should never focus on isolating a single muscle. Instead, bracing and the activation of our entire abdominal wall should be practiced.

People, it’s time we stop getting this wrong. Stop drawing in your belly button, and start working on improving your core stiffness. Your body will thank you for it!

References

1. J Vera-Garcia, J Elvira, S Brown, S McGill. “Effects of abdominal stabilization manoeuvres on the control of spine motion and stability against sudden trunk perturbations.” Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 17 (2007) 556-567.

2. PW Hodges and CA Richardshon. “Ineffecient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis.” Spine 21 (1996): 2640-2650.

3. PW Hodges and CA Richardson. “Altered trunk muscle recruitment in people with low back pain with upper limb movement at different speeds.” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 80 (1999): 1005-1012.

4. Stuart McGill, “Laying the Foundation – Why we need a different approach,” Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance, ed. Stuart McGill, 9-27. Canada: Wabuno Publishers, Backfitpro Inc, 2004.

5. Stuart McGill, “Enhancing Lumbar Spine Stability,” Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance, ed. Stuart McGill, 109-122 Canada: Wabuno Publishers, Backfitpro Inc, 2004.

6. Stuart McGill. Painful Backs: Cause, Corrective Exercises and Progressions to Performance. Perform Better Functional Training Summit. Perform Better. Providence, Rhode Island, US. June 13, 2014.

7. Stuart McGill. Mechanisms and Training Techniques Used for Elite Performance. Perform Better Functional Training Summit. Perform Better. Providence, Rhode Island, US. June 14, 2014.

“Illu trunk muscles“. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Other photos courtesy of Shutterstock.