Confucius said the journey of a thousand miles begins with the first step.

I don’t know much about that, but I do know riding a thousand kilometers, covering thirteen thousand meters of climbing (one and a half times up Mount Everest), accruing up to one hundred and eighty kilometers on some days, requires some training.

I’m not sure what it is about my personality that every now and then decides to see exactly what I can do physically, often in a way that seems to be the most self-destructive. Late last year I looked in the mirror and decided I didn’t like what I saw. It’s not that I was fat or unfit, far from it. But I wasn’t anywhere near MY definition of fit.

What brought this on was the realization that in an effort to boost my strength I had slowly been gaining weight. And while my strength had gone up, my relative strength (strength to weight ratio) had not. So, what was the point of being bigger if it didn’t make me better? Around this same time I found a charity group about to embark on a ride to raise awareness for cancer screening – 1000kms from Canberra to Melbourne via some of the steepest terrain they could find.

Within the RKC community there is a little thing called the “What The Hell Effect.” It comes from a slew of Russian research on various kettlebell training regimes that found a kettlebell program often gave benefits in completely unrelated areas. So, armed with the WTH Effect and a serious case of self-destructive attitude I set about trying to see just what was possible with a largely kettlebell-only based training regime as a platform for something epic.

I began training for a thousand kilometer ride with only three months before we began, not having ridden in about four years.

Now at this point you’re probably thinking I busted out my kettlebell voodoo magic and did some swings and was good as gold and rode 1000kms like I was in the Pro Tour.

And you’d be dead wrong.

Unlike some well-known fitness authors I’m not going to fill the room with smoke and perform sleight of hand tricks trying to teach you how to hack performance. No, I’m going to tell you if you want to ride 1000kms you better get on your bike and start riding. I’m also not going to tell you to spend time on short duration, high-intensity sessions.

In fact, I hate to break it to you, but if you want to ride up to nine hours a day for seven days straight, you better start putting in some serious saddle time.

And so I did. Here’s my basic training week:

- Monday – Rest day from cycling. 2 x 5 of: Double kettlebell press, pull ups, pistols, kettlebell front squats, and finish with either some snatches or swings.

- Tuesday – Same workout as Monday. Ride two hours.

- Wednesday – Same workout as Monday. Ride Three hours.

- Thursday – Rest day from strength work. Ride three hours.

- Friday – Same strength workout as Monday. Rest day from cycling.

- Saturday – Same strength workout as Monday. Ride two hours.

- Sunday – Rest day from strength work. Ride four hours.

The vast majority of these rides in the first two months were at a low enough intensity that I could talk the entire time while riding in a panting conversation. I rode without any kind of heart rate monitor, power meter, or GPS – solely on perceived effort – and I used this simple talk test as a means of figuring how hard I rode and whether or not I needed to slow down.

The sole goal of this was to get as many miles into my legs as I could, as often as possible. Harder efforts would have needed longer recovery and also meant my crucial aerobic pathway was not being trained. In a recent blog post, endurance wunderkind Dr. Michele Ferrari (formerly Lance Armstrong’s physician) made some observations about fat and carbohydrate usage and the relative intensities they were used at :

The sole goal of this was to get as many miles into my legs as I could, as often as possible. Harder efforts would have needed longer recovery and also meant my crucial aerobic pathway was not being trained. In a recent blog post, endurance wunderkind Dr. Michele Ferrari (formerly Lance Armstrong’s physician) made some observations about fat and carbohydrate usage and the relative intensities they were used at :

70% of the average VO2max value of elite athletes (VO2max = 75ml/kg/min): impossible to hold this intensity of effort without a significant contribution of CHO as fuel…this intensity is relatively low for his aerobic engine, representing around 50% of his VO2max…at such low intensity (for him) utilizes 40% carbohydrate and 60% fats as fuel.

Even an athlete of Armstrong’s capacity can only store roughly 700-800g of carbohydrate (roughly 3000kcals) in their body, meaning it is necessary to either non-stop fuel the body with carbohydrate or teach the body to more effectively use fat as a power source.

This flies in the face of what is typically told in the fitness industry – that fat is still burnt at relatively the same amount even as intensity climbs. It is just untrue, as top endurance researchers are now finding.

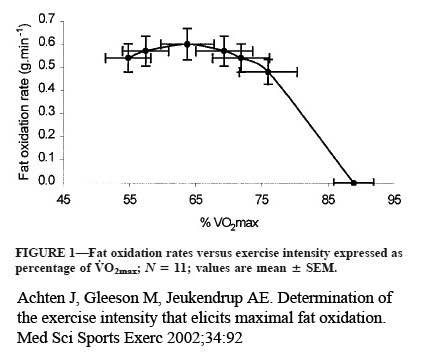

The chart below shows the rate of fat oxidation dropping off rapidly beyond 75% of VO2Max. (Please note: I am not entering into a debate about high- versus low- intensity for shedding body fat. This is only about the ability to use fat as a fuel source).

And so we began the ride. I knew I was in for a hard week when I started seeing the guys with whom I would be riding – many had raced, some had completed multiple Ironman triathlons, my roommate had even medaled at the Australian Masters’ Games in the road race! All of a sudden my ability to do pistols and weighted pull ups didn’t seem so important. Surrounded by shaved legs and shiny bikes, we began.

DAY ONE

The first day was easy – only 120kms on a mostly flat road. The pace was light and everyone was settling in, getting to know one another, or renewing friendships from the year before.

Then it got real.

DAY TWO

Day two featured enough climbing to get you almost a third of the way up Everest (no mean feat, as the majority of mountains in Australia are only about 20% as high as the great peak – meaning we had multiple long climbs for the day). With little cycling background and scant preparation, as soon as the road tilted up I was spat out the back and stayed there for  hours on my own. Probably the only quality I have that is useful athletically is my bastard stubbornness. And that’s what kept me out of the van all day long at the back of the pack on my own.

hours on my own. Probably the only quality I have that is useful athletically is my bastard stubbornness. And that’s what kept me out of the van all day long at the back of the pack on my own.

But a funny thing happened. On the final climb, an eight-kilometer, 8% gradient, I started passing people and finished the climb fifth. Anyone who rides with me will tell you I am anal about nutrition and hydration, as the only way to keep my body chugging along was to non-stop down carbohydrates to make up for the fact I was redlining myself all day long. Others hadn’t been so wise and many had to stop at various points up this long, steep climb.

On the final run into town for the night, I was in second! You can imagine my joy after being last for nearly the entire day. And while not a race, being the slowest is always hard to bear.

DAY THREE

Day three was awful. Having ridden near my limit all day the day before I was wasted. So bad I didn’t even want to ride in the group that day for fear of causing an accident, even though it would mean saving precious energy by hiding from the wind. At lunch I don’t even remember speaking to anyone, I was so tired.

But following my trend from the day before I started to come good around 5:00pm that night – after riding for almost nine hours that day – for the final 20km climb into our stop for the night.

DAY FOUR

Thankfully day four was flat all day long and even at 140kms, which would have been my longest ride ever previously, after two days of 170+kms it felt like a rest. We were blessed with good weather that day and rode with the winds at our backs and bright, mild sunshine all day long. The effect of this “rest” day was noticeable in the group and we arrived at our stop for the night full of humor and energy.

DAY FIVE

Day five was a quick trip up an iconic mountain in my home state (Mt. Buller), and at 100kms roughly again, the day was “easy.” Funny, because only two months prior I had been so tired getting to the top of it I was almost unable to get my foot out of the pedal!

DAY SIX

Day six was another 140km day, with only a hard 60km stint near the end. So hard in fact I shredded my rear tire on the final descent trying to outrun the rain that was coming.

That just left the final day home – an easy 70kms.

What I Learned:

- I’m not a great cyclist. At the slightest hint of anything that went even the slightest bit upwards I was out the back of the group immediately. But, as I wrote about, endurance work, particularly cycling, still has a large strength component. So even though I’m not a great cyclist, my large strength base allowed me to cover up on anything that wasn’t hilly.

Despite not having much riding base, I was used to training two times per day and working reasonably hard during those sessions. Riding on tired legs after my strength workouts gave me the same feeling I knew I’d be facing towards the end of each day and I had prepared myself mentally for that feeling.

Despite not having much riding base, I was used to training two times per day and working reasonably hard during those sessions. Riding on tired legs after my strength workouts gave me the same feeling I knew I’d be facing towards the end of each day and I had prepared myself mentally for that feeling.- This event was one of the single best things I have ever done. It was tough and at times I doubted myself. From great suffering comes, I believe, great reward and insight. The cause is a worthy one and the group of guys among the finest I have ever met under any circumstances anywhere in the world. To find twenty men who feel so strongly about raising awareness for cancer screening they are willing to put their lives on hold and suffer through this kind of hardship is rare and I’m already wondering how I can organize my life to get on this event again next year.

The charity was as worthy as they come. The Jodi Lee Foundation educates on the benefits of bowel cancer screening. As many as one in twelve Australians will die of bowel cancer every year – a number three times higher than our annual road toll. Yet in 90% of cases the disease can be treated if caught early enough. If you feel like donating to such a worthy cause please go to www.jodileefoundation.com and see the details for The Ride for the Little Black Dress.