No pain, no gain. Right?

What if we told you there are three easy ways to get equal (or better) results from your workout, with less pain afterward? You don’t even have to change much. You just have to make small adjustments to your exercise plan to get similar gains with less post-exercise soreness.

Sounds too good to be true?

The Good News About DOMS

Keep in mind, we can’t eliminate soreness, but we can reduce it. The pain experienced several hours or days after exercise is known as delayed onset muscle soreness, or DOMS. Contrary to popular belief, getting DOMS does not always translate into building more muscle and can actually cause more harm than good. So in reality, sometimes more pain means less gain.

We are researchers and practitioners at the Center for Sport Performance at California State University, Fullerton. One recent study from our lab showed aerobic exercise (or even a cool-down) can help reduce post-exercise muscle soreness. Moreover, some supplements like caffeine and fish oil can also help.

But today, we’re going to give you three strategies to prevent it from happening in the first place that won’t compromise your results.

1. Progress Slowly

We have witnessed a well-trained college football player perform twenty repetition of a barbell back squat at 85% of his 1RM (~350lbs) and then two days later watched him succumb to tears while trying to get out of his car. He was unable to do a full squat for over two weeks.

The point being, post-exercise soreness cannot only be painful and annoying, but it can significantly inhibit your subsequent training. More soreness does not equal more muscle growth. This football player would have been better off doing ten or twelve repetitions at that weight, then repeating that every two or three days for two weeks.

“Contrary to popular belief, getting DOMS does not always translate into building more muscle and can actually cause more harm than good. So in reality, sometimes more pain means less gain.”

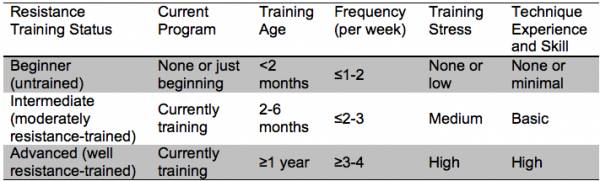

The truth is, enormous gains in strength and power can happen with SUB-maximal exercise. Unless you have been training hard, consistently, and injury free for a year or more, you’re not considered “advanced” (see Table 1). Therefore, when starting a training program, progress more slowly than you think, even if you have previous training history. This is especially true for beginner or intermediate exercisers (as outlined in Table 1). Keep your eye on the results you’ll get one month or even one year from now.

TABLE 1: Example of Classifying Resistance Training Status

Adapted from: Thomas R. Baechle and Roger W. Earle, “Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. 3rd Edition.” Chapter 15, Table 15.1, p 384. (Human Kinetics, Champagne, IL. 2008).

For the first one to two weeks of a new exercise program, keep your effort level at a maximum of five out of ten (one being laying on the couch and ten being all-out exertion). You may feel like you’re “being lazy” because you know you could be working harder, but trust us, long-term adaptations are not the result of your first two weeks.

Take it slow, and remember: even if you do less during the first two weeks, you will recover faster to train harder later, putting you at the same spot (or further ahead) a few weeks down the road. During these first two weeks, you should feel a little tight and sore for a day or two after training, but no more or longer than that.

“Take it slow, and remember: even if you do less during the first two weeks, you will recover faster to train harder later, putting you at the same spot (or further ahead) a few weeks down the road.”

After weeks three or four, you can move up to a perceived effort of seven out of ten. Do this as long as you are not more than moderately sore.

If things are still going well after the first month, continue increasing your effort. You’ll notice you get less sore with more effort. Your goal is to never get too sore. If your recovery lasts more than two to three days, you have done too much too quickly.

This soreness is a major cause of people giving up on their exercise routines. Progress slowly, so you can train harder later.

2. Limit Eccentric Exercises

Muscle contractions are classified as concentric (muscle shortening), eccentric (muscle lengthening), or isometric (constant length). Eccentric contractions usually occur when weight is lowered (e.g. when you lower the bar to your chest during a bench press).

Another way to think of this is:

- Concentric = when you are moving the weight.

- Eccentric = when you are fighting gravity to stop the weight from moving.

Eccentric contractions are most associated with DOMS. While they do stimulate muscle growth, we recommend limiting (but not removing) heavy eccentric exercises during the initial phases of a fitness routine, especially for beginner/intermediate exercisers or when trying a new exercise. The true goal of the first weeks of an exercise routine is not to build muscle, but to get accustomed to new movements and establish baseline fitness.

“[W]e recommend limiting (but not removing) heavy eccentric exercises during the initial phases of a fitness routine, especially for beginner/intermediate exercisers or when trying a new exercise.”

There are several ways to alter your current workout routine to minimize eccentric actions:

- Use an Airdyne (or Air Assault) stationary bike for aerobic/conditioning training.

- If you have access to the proper equipment (i.e. rubber plates), drop the bar instead of lowering it to the ground after each deadlift repetition.

- Instead of level or downhill running, run uphill.

- Instead of using a leg press machine, push a sled.

- Minimize or even eliminate the landing portion of jumping exercises (especially for lots of repetitions). Pick a different movement entirely or change the jumping so landing is minimized (e.g. landing on a soft box/pad, stepping down, and then jumping again versus jumping and landing on the ground).

3. Consume Protein

Adequate protein consumption is not only essential for building muscle mass, but ingesting protein during and after exercise has also been shown to decrease post-exercise muscle damage.2 This likely occurs by stimulating protein synthesis, providing muscles with nutrients needed to repair and rebuild damage.

Protein comes from a variety of sources. You might prefer getting your protein from solid foods (such as meat) or supplements (i.e. powder, bars, liquids, etc.).

More Like This:

- DOMS: The Good, the Bad, and What It Really Means For Your Training

- Just How Sore Are You? Science Uses Infra-Red to Measure DOMS

- 3 Reasons You Don’t Squat More (And What to Do About It)

- New on Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Thomas R. Baechle and Roger W. Earle, Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. 3rd Edition. Chapter 15, Table 15.1, p. 384. Champagne, IL, 2008.

2. Michael J. Saunders et. al., “Consumption Of An Oral Carbohydrate-protein Gel Improves Cycling Endurance And Prevents Postexercise Muscle Damage,” J. Strength and Cond. Res., 21(3), 678-684, 2007.

3. James J. Tufano, et. al., “Effect Of Aerobic Recovery Intensity On Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness And Strength,” J. Strength and Cond. Res., 26(10), 2777-2782, 2012.

Photo 1 courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photography.

Photo 2 courtesy of CrossFit Impulse.

Photo 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.