Charles is here on a weekly basis to help you cut through the B.S. and get some real perspective regarding health and training. Please post feedback or questions to Charles directly in the comments below this article.

Over the past several months, I’ve reposted a number of videos on my social media accounts from well-known mixed martial arts (MMA) competitors and their strength coaches. These clips portray the athlete performing unique but dangerous and ineffectual exercises, such as the following example I’ve picked for illustration purposes. Please have a quick watch and then I’ll rejoin you below:

Jon Jones:

I initially assumed the first video was a spoof, but am now convinced it is not. I don’t know where to start in terms of analysis. Assuming that Silva is trying to train his legs here, if you were to list the 10,000 different ways you could train legs, ranked from best to worst, this maneuver would be #10,000. If he ditched the mask and didn’t smash his knees on the floor on every rep, I’d be willing to upgrade it to 9,999. Almost any leg exercise you can think of would be safer and more effective than this – even split squats while standing on a BOSU.

In the second video, Jon Jones is doing weighted sit ups, a debatable exercise right from the start. To make a bad exercise many orders of magnitude more dangerous, he’s holding a barbell behind his neck, with a wide grip. This places incredibly destructive forces on the shoulders, and for what benefit?

How do coaches come up with this nonsense, and why do their athletes buy into it?

What Is That Coach Thinking?

Addressing the first question, most coaches feel an almost overwhelming need to differentiate themselves from their competitors. On its own, this isn’t a bad thing. But in their efforts to stand out from the crowd, some of these coaches resort to strategies and methods that are unique for the sake of being unique.

In other words, uniqueness, rather than effectiveness, becomes the overriding goal. As you’ll see when I outline the approach I would take with combat athletes, effective and unique don’t usually share a lot of common ground.

Why Do Athletes Go Along With It?

Why do top-level athletes get suckered into bad coaching environments? Lots of reasons.

Most significantly, world level athletes are people too, just like you and me. Often they don’t have the proper context to recognize superior coaching when they’re exposed to it. So they might lean on recommendations from other athletes, which seems reasonable enough at first glance.

Problem is, as we saw above, many top-tier athletes have terrible strength and conditioning programs. Because they are innately talented with strong work ethic, these athletes succeed in spite of the strength training they do, rather than because of it. Bottom line: even smart, savvy people need to check their instincts when shopping for a strength coach.

How I Would Train a Fighter

First, all ancillary training modalities, including strength training, must improve athletic characteristics that the athlete’s sport practice doesn’t adequately address by itself. If the athlete’s sport training leads to strong leg muscles, as an example, I’m likely to avoid leg training in the weight room.

Second, we can’t always say for certain if a strength training exercise will benefit the athlete. But we do know for sure that it will come at a cost, in terms of energy, time, injury risk, and so on. In my opinion, too many coaches do not appreciate the costs of auxiliary training methods. This point underscores the need for maximum economy in the strength training program. Get in, do 2-3 drills that address the athlete’s weakest links, and get out so he or she can recover for the main activity.

Third, auxiliary strength training drills must be general in nature in order to facilitate maximum positive transfer to the athlete’s sport skills. They also need to be low-skill activities. I don’t see the point in teaching an athlete how to do one sport (Olympic weightlifting, for example) to get better at another sport. If a strength exercise has a significant learning curve that must be navigated, it’ll be quite some time before that exercise can be loaded to the point to where it will actually benefit the athlete. Why not use something like a hack squat machine instead, which has a low skill component and injury risk?

Auxiliary strength training should never come at a cost to primary sport training.

From the above three principles, here is a hypothetical strength program that I’d propose for a “generic” MMA athlete:

Day 1:

- Pull ups

- Barbell hip thrusts

- Weighted push ups

Day 2:

- Weighted push ups

- Machine rows

- Hack squats

The exact exercise menu would depend on the athlete’s unique needs, and the above example serves only to illustrate the principles I shared earlier. Note the decided lack of Olympic lifts (too much of a skill component and low transfer), stability drills (injury risk, no transfer), or “fad” drills and equipment, such as using altitude masks and hitting tires with sledgehammers.

Most strength training innovations have already been developed. While there will inevitably be advancements in the future, that curve is rapidly flattening out as time goes on. In other words, we already have this stuff pretty much figured out.

Why Don’t Many Coaches Take This Approach?

Good question. It’s probably because the exercises listed above seem unremarkable and unimaginative. They lack marketing appeal. Often, however, the most sophisticated, effective approaches seem fairly ho-hum on the surface. The current marketing milieu demands sizzle, not steak. If you don’t stand out in some type of memorable way, you’re unlikely to thrive, no matter how effective you might be.

I have one suggestion for anyone looking to become an effective coach or athlete: Be more enamored with results than the tools or methods that lead to those results. If your goal is to add 30lb of muscle, or to have stronger punches, or to get to 8 percent body fat, and you accomplish that using “boring” tools or methods, does that in any way lessen the accomplishment?

And finally, to repeat a theme I’m always pushing over here, don’t blindly copy the training or nutritional habits of your favorite athlete. Like all of us, the greats make mistakes. Instead, seek to identify the productive aspects of that athlete’s regime, and also the less productive ones. Then, you’ll know what behaviors to mimic, and which ones you’re better off dismissing.

This Week’s Training:

Volume: 71,086lb (Last Week: 65,324lb)

Significant Lifts:

- Low Bar Squat: 315×5

- Bench Press: 215×5

- Deadlift: 440×5

- Military Press: 130×4

Happily, this has been another productive week of training, with a handful of rep PRs and near PRs, and no orthopedic complains whatsoever.

I’ve only been doing lower (5’s) reps for a few weeks now (following about 8 weeks of 8-10 reps) and I’m quite surprised how strong I’m feeling right out of the gate.

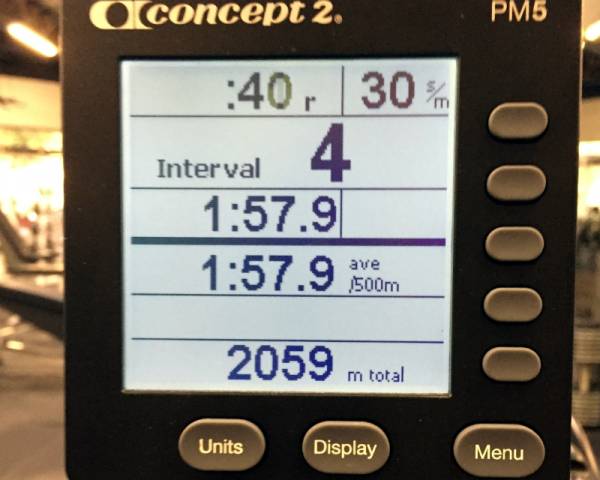

I should mention that I haven’t done any running or kick practice in a bit, mostly because I haven’t had the time and energy to pursue everything I’d like to do simultaneously. With that said, I am developing a fondness for the Concept2 RowErg, partly because it feels safe and productive for me, and also because I like the fact that its display monitor tabulates my stats (see pic below).

I’m a big fan of activities that can be measured and quantified, and the C2 rower is great for that.

I’m also slowly dropping bodyweight. My average weekly weight is 199.2, compared with 200.2 the previous week, so that’s another plus for the week.

I’m guessing that after another few weeks I’ll drop down to sets of 2-3 and see if I can hit some new PRs in that bracket, and then after that, back up to the 8-10 range again.

Monday, February 1, 2016

Bodyweight: 200.8lb

Volume: 21,560lb

Goblet Squat

- Set 1: 35lb × 10

- Set 2: 55lb × 10

- Set 3: 75lb × 10

Low Bar Squat

- Set 1: 45lb × 5

- Set 2: 95lb × 5

- Set 3: 135lb × 5

- Set 4: 135lb × 5

- Set 5: 225lb × 5

- Set 6: 315lb × 5

- Set 7: 275lb × 5

- Set 1: 5 reps

- Set 2: 5 reps

- Set 3: 5 reps

- Set 4: 5 reps

Seated Calf Raise

- Set 1: 90lb × 8

- Set 2: 90lb × 8

- Set 3: 90lb × 8

- Set 4: 90lb × 8

45° Back Extension

- Set 1: +140lb × 8

- Set 2: +140lb × 8

- Set 3: +140lb × 8

- Set 4: +140lb × 8

Tuesday, February 2, 2016

Bodyweight: 199.2lb

Volume: 12,073lb

Bench Press

- Set 1: 45lb × 5

- Set 2: 95lb × 5

- Set 3: 135lb × 5

- Set 4: 185lb × 5

- Set 5: 215lb × 5

- Set 6: 205lb × 5

- Set 7: 185lb × 5

Incline Dumbbell Press

- Set 1: 100lb × 8

- Set 2: 120lb × 8

- Set 3: 120lb × 8

TRX Inverted Row

- Set 1: 5 reps

- Set 2: 5 reps

- Set 3: 5 reps

EZ Bar Curl

- Set 1: 65lb × 8

- Set 2: 65lb × 8

Thursday, February 4, 2016

Bodyweight: 199.2lb

Volume: 17,055lb

Deadlift

- Set 1: 135lb × 5

- Set 2: 135lb × 5

- Set 3: 185lb × 5

- Set 4: 225lb × 5

- Set 5: 285lb × 5

- Set 6: 325lb × 5

- Set 7: 375lb × 3

- Set 8: 440lb × 5 (Video Below)

- Set 1: 45lb × 8

- Set 2: 90lb × 8

- Set 3: 115lb × 8

- Set 4: 140lb × 8

- Set 5: 160lb × 8

Seated Calf Raise

- Set 1: 90lb × 8

- Set 2: 90lb × 8

- Set 3: 90lb × 8

- Set 4: 90lb × 8

Friday, February 5, 2016

Bodyweight: 198.4lb

Volume: 20,398lb

Military Press

- Set 1: 45lb × 10

- Set 2: 65lb × 8

- Set 3: 88lb × 6

- Set 4: 110lb × 5

- Set 5: 120lb × 5

- Set 6: 130lb × 4

- Set 7: 110lb × 5

Bench Press (Dumbbell)

- Set 1: 100lb × 10

- Set 2: 140lb × 8

- Set 3: 170lb × 8

- Set 4: 190lb × 8

- Set 5: 160lb × 8

Pull Up

- Set 1: 5 reps

- Set 2: 5 reps

- Set 3: 5 reps

- Set 4: 5 reps

- Set 5: 5 reps

Lying Dumbbell Tricep Extension

- Set 1: 70lb × 8

- Set 2: 70lb × 8

- Set 3: 70lb × 8

- Set 4: 70lb × 8

Dual Cable Low Cable Curl

- Set 1: 100lb × 8

- Set 2: 100lb × 8

- Set 3: 100lb × 8

- Set 4: 100lb × 8

Saturday, February 6, 2016

Bodyweight: 199.6lb

Rowing

- Set 1: 0.5 km in 0:01:58

- Set 2: 0.5 km in 0:01:58

- Set 3: 0.5 km in 0:01:58

- Set 4: 0.5 km in 0:01:58

More Common Sense Training Strategies

- The 4 Undebatable Fundamentals of Training

- How to Make Your Best Progress by Lifting Every Day

- When Too Much Choice Is Bad for Your Training

- New on Breaking Muscle Today

Photo 1 courtesy of CrossFit Empirical.

Photo 2 courtesy of Charles Staley.