The stereotype of the poet is of a sensitive, bookish individual who uses words to capture the human experience. On the other hand, the stereotype of the warrior is brash, aggressive, concerned with physical domination. And never the twain shall meet. Right?

Wrong, if Cameron Conaway has anything to say about it. Dubbed “The Warrior Poet” by a mentor for his pursuit of both mixed martial arts and expression through the written word, Conaway demonstrates that the values and tools of the warrior and the poet are arguably two sides of the same coin. And he has used these tools in a variety of ways to make a positive impact on the world, as a teacher, a fighter, an author, a speaker, and a human rights advocate.

I had the opportunity to find out from Cameron how he became the Warrior Poet and how he lives this philosophy today.

Cameron’s childhood was less than idyllic, as he endured financial hardship, the challenges of having a father who alternated between being absentee and being abusive, and all the normal issues children and young adults face as they try to learn who they are and want to become. As a teenager, Cameron discovered mixed martial arts, one of the galvanizing influences in his young life, by accident, “walking through the movie rental store looking for porn,” and instead finding a UFC video featuring Ken Shamrock. In his book Caged: Memoirs of a Cage-Fighting Poet, Cameron commented that “Ken was fourteen when Bob (Shamrock, Ken’s adoptive father) rescued him. I was fourteen when Ken’s memoir (Inside the Lion’s Den) rescued me.”

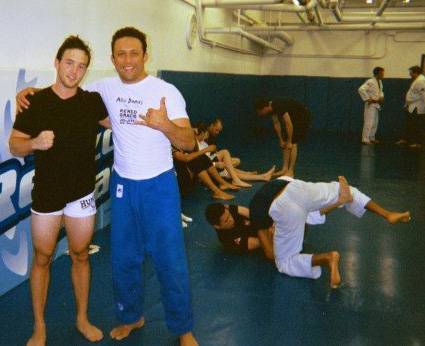

Some fifteen years later, Cameron is still passionate about the sport, claiming it contains all he needs to know. “In a way, the sport filled the gap left by my father. It taught me to be flexible and humble and to strive for well-roundedness.”

Cameron’s childhood experiences also positioned him to take to writing and poetry, given his retreat into his own imagination because of his life circumstances. “I’ve met so many writers with nearly identical stories,” he said. “I was too young and too scared to brazenly confront these issues, so I thought about them and eventually developed a sensitivity to my emotions and the emotions of others.” An introductory poetry class he took in college set the wheels in motion for him to become a writer.

Thus was a fighter-writer, a Warrior Poet forged. To Cameron, the definition goes far beyond his own experiences as a professional MMA fighter and graduate student of poetry. “It’s an awareness of balancing the physical and the mental, of questioning, of not letting bias blind reason.” For him, it is about striking a balance between self-improvement and service to others.

Cameron is retired from MMA, but when he was active, he observed that he was a better fighter when he wrote about it. “To really write a great description of a move or even of an emotional state is to understand it as much as possible.” With every revision of Caged, parts of which he reworked upwards of twenty times, he moved closer to an understanding of what he was trying to convey. “Writing, for me, was the mental equivalent of drilling a move over and over.” Conversely, Cameron also finds that physical health helps him with his writing. “When my diet is solid and I’m in a good rhythm with training, I feel my brain fires quicker and I can get more done in a shorter period of time.”

Cameron is retired from MMA, but when he was active, he observed that he was a better fighter when he wrote about it. “To really write a great description of a move or even of an emotional state is to understand it as much as possible.” With every revision of Caged, parts of which he reworked upwards of twenty times, he moved closer to an understanding of what he was trying to convey. “Writing, for me, was the mental equivalent of drilling a move over and over.” Conversely, Cameron also finds that physical health helps him with his writing. “When my diet is solid and I’m in a good rhythm with training, I feel my brain fires quicker and I can get more done in a shorter period of time.”

And others can understand the confluence. Those who appreciate the complexity of MMA are better able to appreciate Cameron’s love of poetry. And “most poets totally get the fighter side of me. I think it’s overlooked how tough and rebellious they are.” Being a poet in this day and age “is an act of utter rebellion against the status quo.” While Cameron finds poets to be more interested in the fighter side of him than vice versa, “one way to bridge the gap is to believe that we all have fights in life. We’re all fighters in one way or another.” Cameron has developed a series on The Good Men Project called “What’s Your Fight?” that speaks to this belief.

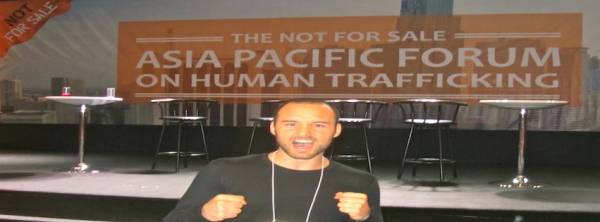

More recently, Cameron’s fight has turned to human trafficking. When his fiancée’s professional and personal goals inspired a move abroad, they chose Thailand. In addition to helping him with his writing (“I can think of no better supplement for a writer to take than travel.”), the trip to Thailand stepped up his pre-existing interest in human rights by exposing him to the grim realities of Thailand’s sex trafficking industry. He was inspired to write Never to Be Sold Again, and since then has attended conferences, written articles, and become the Social Justice editor at The Good Men Project. “Fighting for others is my new fight, and it’s a fight that will last a lifetime.”

More recently, Cameron’s fight has turned to human trafficking. When his fiancée’s professional and personal goals inspired a move abroad, they chose Thailand. In addition to helping him with his writing (“I can think of no better supplement for a writer to take than travel.”), the trip to Thailand stepped up his pre-existing interest in human rights by exposing him to the grim realities of Thailand’s sex trafficking industry. He was inspired to write Never to Be Sold Again, and since then has attended conferences, written articles, and become the Social Justice editor at The Good Men Project. “Fighting for others is my new fight, and it’s a fight that will last a lifetime.”

Read part two of my interview with Cameron to learn other ways he has transformed fighting and poetry into action.