Choices. This is what Corey Reed thinks about every day. He thinks about training choices and nutritional choices, but a big reason why choices are part of his daily reflection is because not a day goes by when he doesn’t think about the accident.

On December 16 it will be eight years since he got into the passenger side of a truck after his best friend and he had been drinking. Partying was just part of their lifestyle then. They were in their early twenties. They were fun, ambitious guys letting off steam. When the truck hit railroad tracks at one hundred miles per hour, it went airborne into a silent void until the passenger side sustained the violent brunt of a collision with a tree. The truck rolled to an obliterated stop. A month later, Corey woke up in the hospital with multiple fractures, a ruptured spleen, and his right leg amputated below the knee. Harder for him to comprehend was that he couldn’t see. Optic nerve damage from the impact had left him blind.

Corey’s mom and dad were in the hospital room when he came to, as they had been through Christmas and New Years while Corey was deep in the coma. As Corey began to discover the traumatic consequences of the accident, his father came over to the hospital bed and draped himself over his son. He said, “We’re in this together.”

“My dad saying that – and my mom being right there too – was the most memorable experience in the hospital,” Corey told me. “There was so much clarity in that moment about how I was supported and what my family meant. Just hearing my dad’s voice…I don’t care what age you are, when you’re that wiped out it was so comforting.” The idea of being in it together no matter how bad the situation seemed or how long it would take gave Corey the foundation from which he could build back his life. And beyond all imagination, build it back he has.

The road to becoming the man Corey is today hasn’t been an easy one, though one would never know it meeting him now. It’s hard to imagine he spent years digging himself out of dark places. During that time, he uncovered a faith in God while he was involved with Extreme Mobility Camp, a nonprofit, faith-based winter camp in Winter Park, Colorado that specializes in recreational skiing and snowboarding for the visually impaired. Through this camp a world of possibilities opened up to Corey, including finding enough faith to let some of that darkness go.

Corey spent years soul searching, and that process has produced not just a man of faith, but a beacon of inspiration. On the surface, Corey is an athlete on the rise. He’s well known in the adaptive action sport scene now where he is back shredding in his pre-accident passions, snowboarding and wakeboarding on a competitive level. But more profoundly, Corey exudes a positivity and grace that privately embarrasses any of us who feel one iota of self-pity. And now he’s showing the CrossFit world the true meaning of the expression “no excuses.”

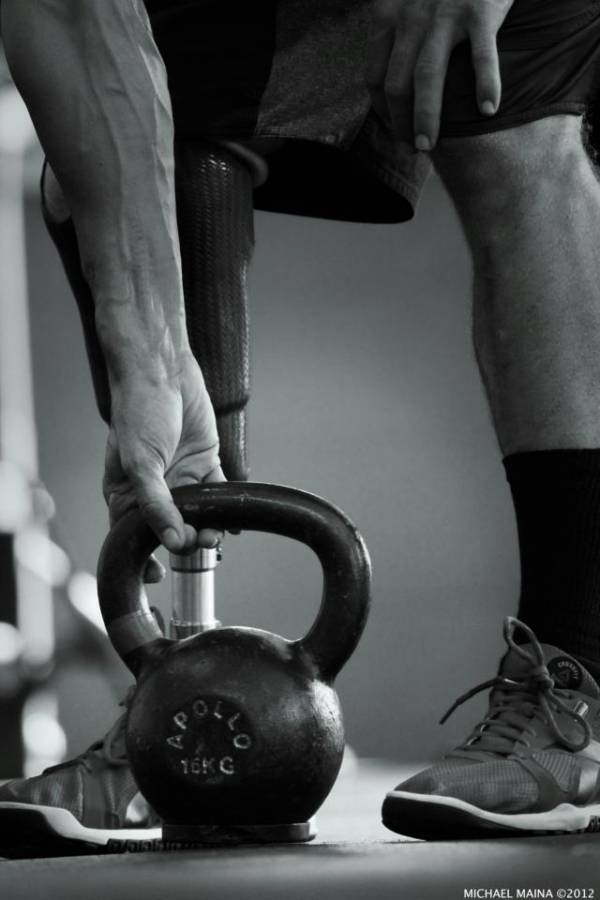

This past October 20, after just a few months of doing CrossFit, Corey was the first adaptive athlete to compete in a CrossFit event at SICFIT’s SICest of the Southwest as part of the CrossFit LA team. Corey had initially sought out CrossFit as a conditioning tool for his other sports. He was introduced to coach Kenny Kane. Then one CrossFit class turned into the idea of taking Corey to a competitive level. In June, Kenny brought Corey into the CFLA team environment and the hardcore training began.

Corey had never done most of the movements before and everyone quickly realized that the adaptation process would not be for Corey alone. Kenny had to creatively find new ways to teach the multitude of movements to an adaptive athlete and the other teammates had to learn the true meaning of trust and being a cohesive team. Often, Kenny blindfolded the rest of the team during training exercises to nail home this trust. “I’ve competed many times before,” said Shirley Brown, Corey’s teammate. “But this was different as it really was about teamwork and communication. It was more about faith, trust, and courage this time, which Corey is full of. I feel blessed to be a part of that.”

Corey had never done most of the movements before and everyone quickly realized that the adaptation process would not be for Corey alone. Kenny had to creatively find new ways to teach the multitude of movements to an adaptive athlete and the other teammates had to learn the true meaning of trust and being a cohesive team. Often, Kenny blindfolded the rest of the team during training exercises to nail home this trust. “I’ve competed many times before,” said Shirley Brown, Corey’s teammate. “But this was different as it really was about teamwork and communication. It was more about faith, trust, and courage this time, which Corey is full of. I feel blessed to be a part of that.”

More extraordinary has been Corey’s ability to learn and progress so quickly. Kenny said, “As a coach, you want athletes who are hungry to get good, take risks, and push themselves beyond their limits. Corey Reed does all of those things.” The day Corey learned box jumps, a movement easily taken for granted, the team and I watched in support. The gym was not brightly lit that day and we sat at enough distance to give Corey and Kenny space. We were quiet, but the energy was charged, which Corey says he felt. He bent over to feel for the box, stood, and in faith jumped, hoping he estimated the height correctly. He stepped down, bent over to feel for the box again, stood and jumped. Every athlete who watched him that day choked up. Corey’s drive was not hitched to doubt or hope, but simply a determination to get it done regardless of anything that has happened. Initially while watching Corey train, the rest of us grappled with our own discomfort and our guilt as able-bodied athletes, but Corey’s unmuddled focus helped us recognize that’s all bullshit. We let it go. He made us braver as athletes.

Corey has had plenty of his own epiphanies during his CrossFit training including an emotional breakthrough when Kenny pushed him to his absolute limit on the rower. The moment was captured on video and it’s a powerful testament to Kenny as a coach and Corey as an athlete, adaptive or not. Kenny likes to call this breakthrough the Orb, when an athlete taps into their pain and breaking point as conduit to a higher source, which leads to the next level as an athlete. Corey did not resist and it was a spiritual moment that forced him to reflect not just on the months he had put into training, but the years since his accident. Corey said, his voice breaking through tears, that training in CrossFit “has given me some identity back for who I was as an athlete.”

All the training culminated at the SICFIT competition. Top elite athletes from around the country watched in awe as Corey gave his all during the event, which included learning a brand new movement the sumo deadlift high pull, minutes before an event. Right before their heat, teammate Zach Goren, took Corey’s hands and placed them on the barbell. He placed his feet to a wide stance. He gave him step by step instructions in minutes. Watching them was like seeing a fluid dance of perfect choreography. Then with a three, two, one countdown Corey was off, Zach by his side the entire time. At the end of the event, after all the top competitors were handed their prizes from the day, SICFIT presented Corey with the inaugural Corey Reed Award for courage and outstanding performance. It moved many to tears especially Kenny and Corey.

All the training culminated at the SICFIT competition. Top elite athletes from around the country watched in awe as Corey gave his all during the event, which included learning a brand new movement the sumo deadlift high pull, minutes before an event. Right before their heat, teammate Zach Goren, took Corey’s hands and placed them on the barbell. He placed his feet to a wide stance. He gave him step by step instructions in minutes. Watching them was like seeing a fluid dance of perfect choreography. Then with a three, two, one countdown Corey was off, Zach by his side the entire time. At the end of the event, after all the top competitors were handed their prizes from the day, SICFIT presented Corey with the inaugural Corey Reed Award for courage and outstanding performance. It moved many to tears especially Kenny and Corey.

The entire experience has Corey hooked on CrossFit. “What I love about CrossFit is the flying around,” he said. “Up on the rings, flying around on the bars. It’s the ultimate mobility training for balance and for a blind person, that’s amazing.” He plans on competing more. On November 10, he will be part of the first CrossFit adaptive event designed for amputees and severely wounded veterans called the Working Wounded Games. Corey will be the only blind competitor.

Corey is busy with many projects including trying to get CrossFit training as part of the Paralympic snowboard team program through the Tahoe Adaptive Competition Center of which Corey is a founding member. Most importantly, Corey is busy with his nonprofit Ride With Core (RWC). RWC, whose motto is “ride with faith, not by sight,” is his lifestyle brand through which he wants to encourage wellness on every level. He is creating a source of positivity by endorsing brands that have made a difference in his life, like the people who make his high-performance prosthetics. Mainly, he’s setting up lectures at schools to talk to kids about their choices. “It’s important to live the choice,” Corey says. “Good or bad we have to live with the choices we make and make the best of those choices.”

Corey is busy with many projects including trying to get CrossFit training as part of the Paralympic snowboard team program through the Tahoe Adaptive Competition Center of which Corey is a founding member. Most importantly, Corey is busy with his nonprofit Ride With Core (RWC). RWC, whose motto is “ride with faith, not by sight,” is his lifestyle brand through which he wants to encourage wellness on every level. He is creating a source of positivity by endorsing brands that have made a difference in his life, like the people who make his high-performance prosthetics. Mainly, he’s setting up lectures at schools to talk to kids about their choices. “It’s important to live the choice,” Corey says. “Good or bad we have to live with the choices we make and make the best of those choices.”

Corey’s near-death experience was a product of a choice he made a long time ago. Through support, he was inspired to get back his drive as an athlete. Every choice since has inspired someone else.

Photos provided by Michael Maina.