“I don’t need the gym. I’m already running 5-6 days per week. That’s plenty!”

Have you ever said something like this? As an endurance athlete, it is easy to buy into the idea that you can just run, bike, or whatever-it-is-you-do all the time, and call it good enough. After all, that is what you are training for, right?

Not exactly.

“I don’t need the gym. I’m already running 5-6 days per week. That’s plenty!”

Have you ever said something like this? As an endurance athlete, it is easy to buy into the idea that you can just run, bike, or whatever-it-is-you-do all the time, and call it good enough. After all, that is what you are training for, right?

Not exactly.

This one-dimensional perspective on fitness is a myth that can set you up for injury, limit your performance, and keep you from aging as well as you possibly can. Adding strength training to your regimen will benefit your future as an athlete and your overall health. Let’s dive into a few of the reasons why, then tackle the sticky details of how to actually make it a part of your already-established routine.

Strength Training and Injury Prevention

Endurance sports are well-loved, and with good reason. They are a great way to stay active, spend time with friends, and burn gobs of calories. But they are not without some negatives. Injury rates, especially for runners, are quite high. Some estimates place the yearly rate at somewhere between 37 to 56%.1 That’s sky high!

Some of the most common injuries amongst endurance athletes include:

- Runner’s knee

- IT band issues

- Shin splints

- Achilles tendonitis/tendinopathy

- Plantar fasciitis

- Stress fractures

Any of those sound familiar? Take a moment and take a mental tally of your friends. How many of them have run across some form of injury or ailment? I’m willing to bet it’s a decent amount.

But why exactly is this the case? It’s because endurance sports are highly repetitive motions that occur primarily in one plane. Think of road running versus basketball—the latter is far more dynamic and multi-directional. The body adapts to the specific demands placed upon it, for better or worse. It is this very concept of specificity that both makes you great at your sport of choice, but can also leave your body with weak areas.

Running in a straight line all the time leaves you prone to weaknesses and injuries. [Photo credit: Peter Mooney | CC BY-SA 2.0]

In the case of road running, your body becomes excellent at running straight ahead, but in the process can lose strength in some of the supporting musculature (hips, adductors, abductors) that would be worked in more multi-directional sports. And it is these secondary muscles that help minimize injury risk by better stabilizing the knees and ankles.

Specific adaptations aside, it is worth noting that we also bring our own, unique set of problems and challenges to the table before we even take up an endurance sport. For example, those who work a desk job will likely bring with them tight hips, weak abdominals and suboptimal glutes. Add these variables to the mix of repetitive motion, and you are really just starting out with poor mechanics and repeating them hundreds and thousands of times. Not exactly a recipe for success.

For that very reason, it is beneficial to include strength training designed to address these areas that may become (or already are) weak. Adding balance to your program will also help you to actively work to improve muscle imbalances or avoid getting them altogether. Doing so goes a long way towards keeping you injury free and in the game.

Durability and Joint Health

Along the same vein of thought is the idea of durability. Your joints see a lot of action, day in and day out, with endurance sports. Durability is all about being able to handle that training load while reducing as much stress on the joints as possible. In turn, this reduces injury risk.

The aim of crafting durability is to strengthen the muscles around the joints, both the prime movers and the supporting muscles, so that the joint itself is left taking up as little stress as possible. Doing so leads to better joint longevity, meaning you can enjoy the sport further into your life. But it isn’t just the muscles that benefit, either. Hitting the weights also strengthens your tendons and ligaments, albeit at a much slower rate.

Building durability is a two-pronged approach. It is as much about taking an intelligent approach to increasing training volume (both in the gym and otherwise), as it is about pursuing resistance training protocols that will strengthen the muscles around your joints, so that they can stand up to the demands you will place on them regularly.

Muscle Mass and Aging

Let’s step away from athletics for a second, and breach the somewhat unpleasant subject of aging. As you age, you lose muscle mass and bone density. It’s an unfortunate reality. Over time, this can cause a loss in your ability to perform daily activities, which will make you increasingly dependent on others.

Studies have shown that adults who do not perform resistance exercise experience muscle mass decline of approximately 5% per decade from 30 to 50 years of age,2 and up to 10% per decade after that.3,4 Loss of bone density falls between 10-30% for every decade of adult life in that same group. The good news? Numerous studies also indicate that strength training programs, whether they use machines or free weights, can increase muscle mass and bone density, helping to ease the process of aging and keep you independent and functional for as long as possible.

Don’t discount the long-term benefits of strength training. Aging well matters, too!

Body Composition and Hormonal Health

Endurance sports and strength training affect our bodies in different ways, especially with regard to body composition and the balancing act of anabolic and catabolic hormones. A prime example of this is when you find yourself training for a long event, such as a marathon or Ironman, and find that despite all the exercise, you are still gaining weight. On one hand, it can often be blamed on adopting the “I can eat whatever I want” mindset that frequently accompanies such training. On the other hand, though, there are often hormones at play that predispose our bodies to break down muscle and hold on to fat.

In general, endurance exercise results in larger acute elevations of cortisol (the stress hormone) than strength and power training. In normal amounts, cortisol is necessary for, and vital to, metabolic function. When training volumes are high, however, it becomes increasingly difficult to recover completely, which can result in chronic elevations of cortisol. This leads to the impaired stress response that is almost always associated with low testosterone in endurance athletes.

Excessive cortisol levels are problematic because they have a catabolic effect on muscle tissue. Catabolic hormones are those that serve the metabolic role of breaking things down (e.g., the breakdown of muscle tissue for energy in long-distance athletes). Anabolic hormones (such as testosterone) serve the opposite role of building things up (such as muscle).

Excessive cortisol levels such as those seen in endurance athletes ruin your muscles. [Photo credit: Rob124 | CC BY 2.0]

High training volumes tend to break down muscle tissue and make it more difficult to build muscle. Persistently elevated cortisol levels also cause our bodies to store fat—the other reason folks struggle with weight gain when training.

In addition to these difficulties, when catabolic hormones remain chronically elevated, athletes begin to fight with persistent inflammation and suppressed immune function. That is why it is so common for endurance athletes to have high rates of colds and illness during high-volume training phases.

While running a few miles several days a week is unlikely to cause any such disturbances, if you find yourself in a situation involving higher training volumes (1-2+ hours, 6-7 days per week), the addition of strength training can help you to better maintain hormonal balance and stay on top of your body composition goals.

Strength Capacity and Maximizing Performance

The final reason to consider strength training in your program is really the simplest: Endurance sports are submaximal efforts, and improving your maximal strength tends to improve your ability to produce effort at lower intensities.

How exactly? Strength training not only builds muscle, but it also teaches your brain and body to recruit more muscle fibers per contraction, even at lower intensities. Add to that improvements in VO2 max (oxygen consumption), and you have a recipe for success! Essentially, by building a better engine, you have more horsepower to work with across the board. Who doesn’t want that?

In fact, a 2010 study5 showed that concurrent training (strength and cardio together) actually resulted in better long-term (greater than 30 min) and short-term (less than 15 min) endurance capacity. This proved true both in well-trained individuals and highly-trained, top-level endurance athletes. Adding strength can not only help keep you in balance, but also boost overall performance.

How to Add Strength to Endurance Training

Okay, the reasons are many for including strength training in your program, but where do you start?

Bilateral Day, Unilateral Day

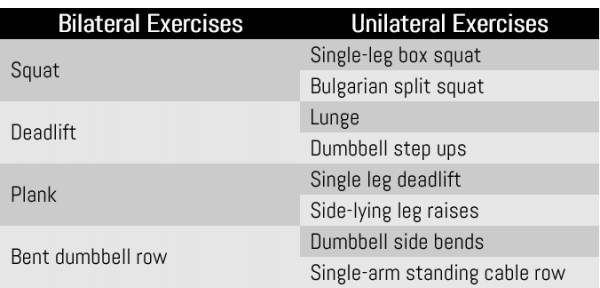

A good place to begin is to plan for two days in the gym each week. One of your training sessions should focus on multi-joint, bilateral movements such as squats, deadlifts, lat pull downs, etc. These sessions are all about building durability, improving maximum strength, and developing muscular endurance specific to your sport.

The other session is all about addressing your weaknesses, and working on stability and core strength. This session shifts focus away from the bilateral movements in favor of more unilateral exercises (e.g. single leg deadlifts vs. traditional deadlifts).

By choosing movements that require balance and stabilization, you pull your core and stabilizing muscles into the mix; areas that often get neglected in your day-to-day endurance training. If you have any known muscle imbalances or past injuries that need addressed, this session is also the place to correct those.

Examples of unilateral versus bilateral movements.

Phases Through the Season

As you draw nearer to your target event(s), your training plan should become more race-specific. This applies to your strength training just as much as it does to your endurance workouts. Use the following guideline to structure your strength training throughout your upcoming season:

- Pre- and Early Season: Focus on low to moderate weight with high repetitions (20-30 reps) for 2-3 sets. 8-10 total exercises.

- Base Phases (low-intensity, high-volume endurance training): Take 2-3 weeks to transition with 2-3 sets of 8-12 reps of moderate weight. Then spend 4-6 weeks building maximal strength with 2-3 sets of 3-6 reps at higher weights. 6-8 total exercises.

- Build Phases (higher intensity, lower volume endurance workouts): Switch into maintenance mode with 1-2 sets of 8-12 reps at moderate weights. 6-8 total exercises. You will be getting most of your strength from the higher intensities found in your endurance workouts during this phase.

Come race day, you can believe what your body is telling you:

References:

1. van Mechelen, Willem. “Running injuries.” Sports Medicine 14, no. 5 (1992): 320-335.

2. Flack, Kyle D., Kevin P. Davy, Matthew W. Hulver, Richard A. Winett, Madlyn I. Frisard, and Brenda M. Davy. “Aging, resistance training, and diabetes prevention.” Journal of Aging Research 2011 (2010).

3. Campbell, Wayne W., Marilyn C. Crim, Vernon R. Young, and William J. Evans. “Increased energy requirements and changes in body composition with resistance training in older adults.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 60, no. 2 (1994): 167-175.

4. Fiatarone, Maria A., Elizabeth C. Marks, Nancy D. Ryan, Carol N. Meredith, Lewis A. Lipsitz, and William J. Evans. “High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians: effects on skeletal muscle.” JAMA 263, no. 22 (1990): 3029-3034.

5. Aagaard, Per, and Jesper L. Andersen. “Effects of strength training on endurance capacity in top-level endurance athletes.” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 20, no. s2 (2010): 39-47.