Arnold Schwarzenegger once said, “Pay no attention to the people who say it can’t be done…

Arnold Schwarzenegger once said, “Pay no attention to the people who say it can’t be done… I always listen to myself and say, ‘Yes, you can.’” This quote can be applied to many things in life, but it takes on a powerful meaning when applied inside the gym walls. Feats of great improbability and goals of inordinate merit are often met with skepticism and doubt, but it is the fire inside and the commitment you give to yourself and your coach that produces success. There is no greater feeling than achieving these goals despite the disparagement of peers.

An athlete of mine recently became a nationally ranked powerlifter in just six months of training. This man has had two previous shoulder surgeries, is 60 years old, and hadn’t been in a gym since high school. He was also suffering from sciatic nerve pain. Below I will outline the details of the training program that helped him accomplish this feat.

Two Months to Build a Base

Older athletes must be trained differently than your typical young, healthy athlete. There is a greater emphasis on recovery and mobility, which in competitive powerlifting, go hand in hand. In order to maximize recovery while maintaining high intensity during sessions, we only trained twice a week.

The first two months of training were significantly different than the following four months. My athlete needed to gradually build into the type of training that would maximize long-term strength gains, and in order to do that, our training needed to be tailored to his current ability.

Our sessions in the first two months started with roughly 20 minutes of a mobility-focused warm up that slowly elevated the heart rate. Following this would be 20 minutes of what I call feedback strength training.

Feedback strength training is a technique that I use when an athlete is first learning a movement. The coach provides feedback while the athlete performs the movement, and makes adjustments before moving forward. For ideal feedback strength training, a large number of sets with a relatively low number of reps yields the best results. Something like 6×3 deadlifts would be a great example of this. You want the number of reps to be enough to learn and repeat the correct motor pattern, but not so many that the body is overloaded and breaks down, which a high-rep scheme might cause.

The reason for doing a large number of sets is to reinforce new motor patterns with volume. This also allows a newer athlete to adjust the amount of rest in between sets to avoid fatigue. If an athlete starts to break down on a set, add another minute or two of rest between sets and allow them to get back into moving correctly. The large amount of sets also allows more opportunities for the coach to give feedback. If you are doing six sets, it is six times where the coach and athlete can talk about what went wrong and how to move better on the next set.

The final 20 minutes of training would include a short metabolic conditioning workout, as well as a warm down and either stretching or smashing out. The goal of the metabolic conditioning was to increase his cardiorespiratory capacity for overall health, as well as target weaknesses otherwise not covered in previous training. If grip seemed to be a weakness, then the metabolic conditioning workout would involve a lot of grip heavy exercises in order to build it up.

Cardiorespiratory capacity is often overlooked in powerlifting, but that is a mistake. If you were to go to a competition in poor cardio shape, a simple dynamic warm up might have you gasping for air, ultimately negatively affecting your lifts. There is a baseline that needs to be maintained for proper performance, and a simple 5 or 10-minute metabolic conditioning workout will allow for this.

At the end of the session was one of the most important pieces, stretching or smashing out. We would use a lacrosse ball or foam roller to dig into muscle groups that were tight, such as the hamstrings or quadriceps. If the hips were extra tight, then we would do some static stretching. I believe this was the main reason we were able to continuously train so rigorously without injury.

Below is a table outlining what a week looked like for the first two months of training:

Four Months of Competition Prep

The final four months of training were split into two, eight-week mesocycles. Each eight-week cycle would consist of a changing rep and set scheme, but maintained the same overall volume. For my athlete, the magic volume ranged between 20-24 total reps for each exercise in the session, with the exception of the last few weeks of each cycle. Finding the magic number depends upon how the athlete responds to training in the first two months of the six-month program. For my athlete, this was the amount of volume that brought him to the brink of breaking down completely, but was still able to maintain proper form.

Before starting the true strength training portion of the six-month program, a max was established for each lift: squat, bench, and deadlift. This allowed the athlete to understand reasonable weights for a given number of reps, as well as providing a point for comparison at the end of each cycle to see overall improvement.

The beautiful thing about this program is that there is built-in improvement within each cycle that gives the athlete positive feedback. The breakdown of each session remained similar to the first two months, but instead of 20 minutes of feedback strength training, there were 30 minutes of standard strength training and 10 minutes of conditioning and smashing out.

Each cycle would start with a low number of sets and a relatively high volume of reps, and progressively grow the number of sets and decrease the number of reps each week, careful to keep overall volume close to the same. Along with this, the goal was to increase 5kg each week, which was easily done, given the decrease in consecutive reps from the previous week.

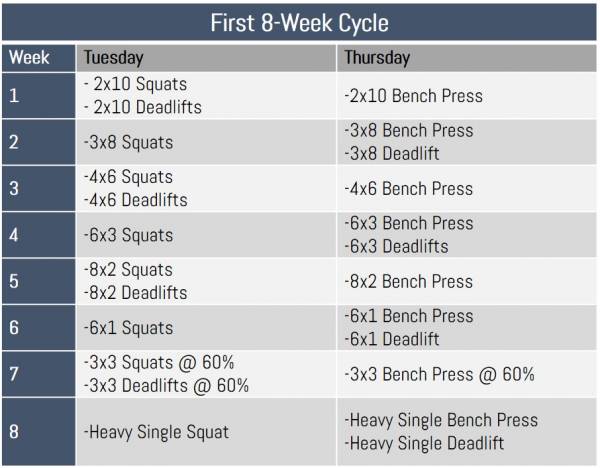

As the cycle progressed, my athlete was lifting significantly more weight for the same total volume. As the reps got close to singles, the total volume decreased slightly. The seventh week was a deload week, and the eighth week was a test/competition week. Below is a chart detailing strength work for the first eight-week cycle:

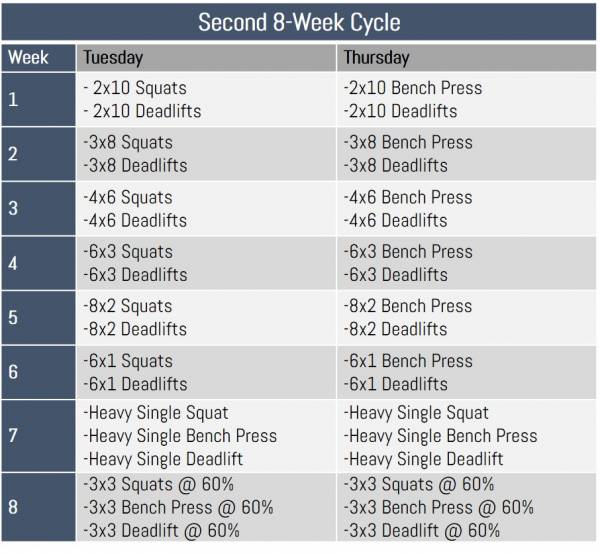

The second eight-week cycle varied slightly, in that the deadlift was now both Tuesday and Thursday, and the 7th week included all three lifts on both days with reduced overall volume to get ready for the competition. The chart below details the final eight-week cycle.

Set Crazy Goals, Achieve Them Anyway

My athlete wanted to compete in powerlifting and set his goals high. He never took his eye off of the prize, and complied with every aspect of the program with 100% commitment. Achieving goals requires patience, perseverance, and a strong will. It brings me great joy as a coach to see my clients succeed, and I believe the more I can share my knowledge, the greater chance more athletes will be able to benefit from it. With strong internal motivation and a smart program, you can achieve success no matter how high you set your sights.