Exercise is one of the most effective methods of combatting obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Through daily activity, you can prevent fat storage, eliminate excess body fat, keep your arteries free of cholesterol, and encourage more efficient cardiovascular and muscular function.

But, according to a new study, it’s not just any exercise that improves your health.

As the researchers discovered, increasing your muscle metabolism, via resistance training, prevents obesity and diabetes in mice and might have implications for future therapies for humans.

The University of Iowa researchers discovered that increasing certain types of metabolic stress helped to increase the production and secretion of a hormone called fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21) in mice. The FGF21 hormone led to improved metabolic function, even going as far as protecting the mice completely from diabetes and obesity. The mice’s high-fat diet had no negative effect on their health thanks to the FGF21 hormone. What’s more, triggering the production of this hormone helped to reverse the mice’s diabetes and obesity, returning them to normal blood sugar levels and weight.

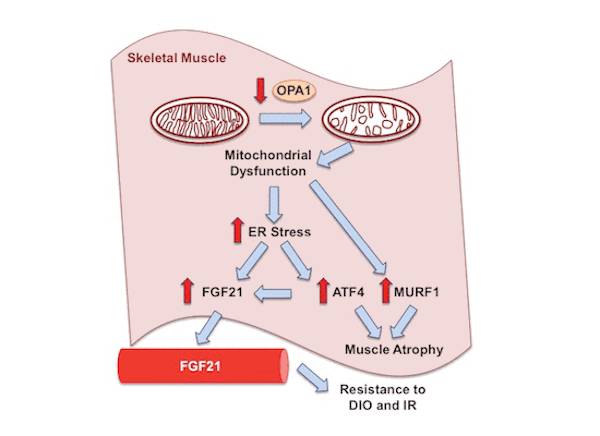

The research, published in the EMBO Journal, details how a little bit of metabolic stress (known as hormesis) can improve our health. When the mice’s muscle metabolism was strained (by the genetic disruption of the OPA1 mitochondrial protein), the mice saw an increase in endurance, preservation in energy expenditure among older mice, and protection from both glucose intolerance and weight gain.

The muscles are responsible for producing FGF21, and higher levels of this hormone correlate with decreased levels of OPA1. As the study discovered, even a small amount of muscle metabolism stress (triggered by resistance training) led to a significant increase in FGF21 production, which in turn led to a decrease in OPA1. Thanks to that OPA1 reduction, the mice were less likely to suffer from diabetes and obesity.

“The general conclusion from our study is there is probably a sweet spot ‘hormetically,’ where creating a little bit of muscle stress could be of metabolic benefit.” Says E. Dale Abel, MD, PhD, professor and DEO of internal medicine at the UI Carver College of Medicine and director of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center at the UI.

“The follow up work on this will be understanding how a little bit of mitochondrial stress can actually increase the ER stress response and if we can mimic that safely,” Abel says. “There are agents that have been used to activate ER stress pathways. So, I think the opportunity here would be to find ways to turn on this pathway in a very controlled way to get enough of this subsequent FGF21 response in muscle to be of benefit.”

Returning to the idea of a “sweet spot” for this stress-induced production of FGF21, Abel notes that other researchers have shown that complete loss of OPA1 pushed the pathway too far and resulted in fatal muscle atrophy in mice.

“Like everything else, this effect can be a two-edged sword, and too much of a good thing can be bad,” he says. “For this to be therapeutically useful, we want to be able to create the effect to the point where we get the benefit but not to overdo it.”

Reference:

1. Renata Oliveira Pereira, Satya M Tadinada, Frederick M Zasadny, Karen Jesus Oliveira, Karla Maria Pereira Pires, Angela Olvera, Jennifer Jeffers, Rhonda Souvenir, Rose Mcglauflin, Alec Seei, Trevor Funari, Hiromi Sesaki, Matthew J Potthoff, Christopher M Adams, Ethan J Anderson, E Dale Abel. “OPA1 deficiency promotes secretion of FGF21 from muscle that prevents obesity and insulin resistance.” The EMBO Journal, 2017; e201696179.