When SUNY Cortland linebacker John Stephens agreed to become a blood marrow donor, he was probably thinking about how his donation might help a little girl with leukemia. It probably never occurred to him that he could be helping his team win, too.

Motivation is a key contributor to success for both individual athletes and teams. Every coach has seen motivated athletes exceed their apparent potential, and every coach has sighed in frustration while talented but unmotivated athletes fell short. From children’s recreational leagues to professional sports, motivated athletes are critical to any coach’s success.

But where does motivation come from? To what extent does motivation (or lack of it) determine the performance of teams and individuals? A study of 224 football players at NCAA Division III colleges tried to answer those questions using the Sports Motivation Scale, a standard survey for assessing athletic motivation. The study drew players from both championship and non-championship teams, with winning percentages of 96.4 and 29.4 percent, respectively. It compared starters to non-starters, and broke participants down by class year and position played.

The results were clear: there were no significant differences in motivation between starters and non-starters, among positions played, or between class years. However, players on championship teams scored higher on every motivational measure. The study examined both extrinsic and intrinsic motivators. Extrinsic motivations include, for example, the desire to earn a championship ring, or win the approval of one’s teammates. Intrinsic motivations include the desire to develop physical skills or improve general fitness. Players on championship teams scored higher on both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations.*

Previous work has found that high intrinsic motivation is correlated with high levels of self-determination: the belief that the individual controls their own destiny. Self-determination and intrinsic motivation manifest in such characteristics as work ethic during practice, dedication to off-season conditioning programs, and so forth.

It is difficult to say whether motivation leads to success, whether a record of success helps motivate further efforts, or both. Still, the authors suggest that coaches can improve their teams’ performance by creating a climate that encourages intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation. For example, athletes might seek the satisfaction of a well-played game or a technically accurate performance, even in the absence of successful results.

Which, strangely enough, is where blood marrow donations come in. Organized team activities around a charitable activity contribute to both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation: athletes gain the goodwill of their peers and their community, while also feeling that they are doing good in the world.

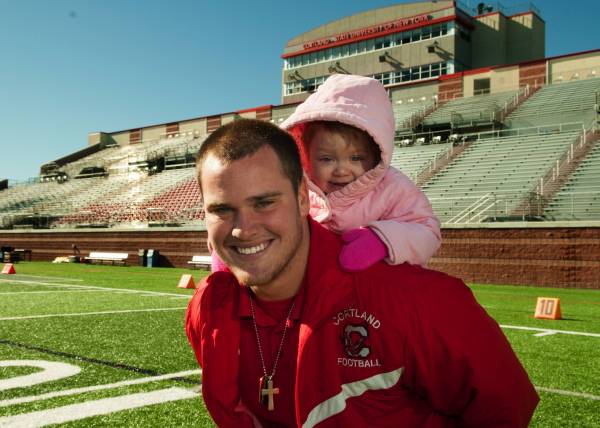

John Stephens probably wasn’t thinking about motivational theory when he visited the SUNY Cortland campus as a prospective student-athlete in 2010. The football team had organized a “Get in the Game, Save a Life” National Marrow Donor Program Drive during his visit. A volunteer swabbed a few cells from his cheek, but told him that donor matches are rare. One thing led to another, though, and in early 2011 he donated bone marrow to Clara Boyle, an infant with leukemia. She is now a thriving two-year-old.

John Stephens probably wasn’t thinking about motivational theory when he visited the SUNY Cortland campus as a prospective student-athlete in 2010. The football team had organized a “Get in the Game, Save a Life” National Marrow Donor Program Drive during his visit. A volunteer swabbed a few cells from his cheek, but told him that donor matches are rare. One thing led to another, though, and in early 2011 he donated bone marrow to Clara Boyle, an infant with leukemia. She is now a thriving two-year-old.

Coincidentally, or maybe not, the SUNY Cortland Red Dragons finished the 2012 campaign with a 9-2 record, and won their first round game in the NCAA Division III tournament.

References:

1. Mark D. Blegen, et. al., “Motivational Differences For Participation Among Championship And Non-Championship Caliber Ncaa Division III Football Teams,” J. Strength and Cond. Res., 26(11), 2924-2928 (2012)

2. L. G. Pelletier, et. al., “Toward a new measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation in sports: The Sport Motivation Scale (SMS),” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 17, 35-53 (1995).

*NCAA Division III schools do not award athletic scholarships, and few professional athletes are recruited from these schools. Financial motivations are probably minimal for athletes in this group.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of Mike Bersani, SUNY Cortland.