I don’t know where the time has gone, but it has now been a quarter century since weightlifting’s first women’s international tournament. This was considered a leap of faith at the time. Up until then the desire of women to venture forth into the very male domain of competitive weightlifting was thought to exist only among the bolder hussies of the West. Vancouver, Washington’s Judy Glenney, wife of a lifter and one herself, was instrumental in getting women’s lifting accepted at both national and international levels in the mid-1980s.

Indeed the early female promoters were mostly from the so-called Anglo Saxon nations of the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia. This was due in no small measure to the vigorous feminist movements that took root there earlier. In looking back one is impressed not so much by the performances, now dwarfed by modern ones, but by the simple willingness for the women to try the traditionally masculine sports and to not consider such activity aberrant. They were also assisted by the legal environments in these jurisdictions, which would not countenance separate treatment. Women wanted to compete, and not with men either, since they, like all athletes, wanted to win.

No one tried to argue that women could be as strong as a man. That was easily refuted. As such, why should women have to settle for the lower echelons of the sport? Due to small numbers, women had to tolerate this at first but soon they did have enough numbers to compete separately even if the entry list was low. Equity would have to rule.

Some of the early stars help in the sport’s acceptance. One was Csilla Földi, daughter of five-time Hungarian Olympian Imre Földi. Though not a world beater, I am now certain that she and her legendary father-coach gave the idea of women’s lifting a lot of legitimacy in the first women’s international tournament, held in Hungary, their home country and also that of the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF). Soon the minds of its erstwhile skeptical sport leaders were shifting. Its future was still uncertain, but the early results were enough that the IWF wanted to continue. The first Worlds were held in 1987 in Florida. Soon Bulgaria had many of the early champions, followed by China. The latter soon forced all others to aim for the silvers only. They were eventually joined by the other East Bloc countries. Once again the West was relegated to the lower echelons.

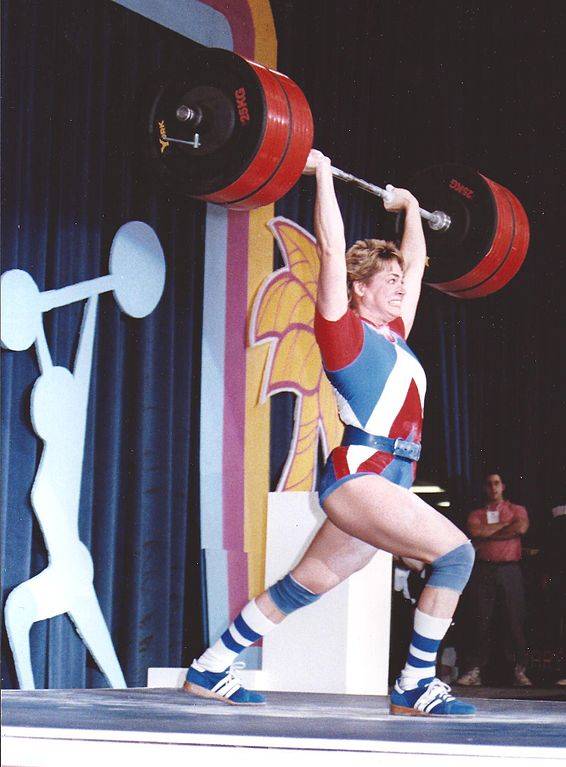

At first many thought women’s performances would never top a certain level. Each observer had his own idea of how high that would be, but the one thing they all had in common was that all would prove too low. I remember when Karyn Marshall of the United States broke the 300lb barrier. (Pictured to the right) She was well ahead of anyone else in the 1987 Worlds so many assumed she had topped out for women. This was greater than anyone else in history, topping the nearly century old Guinness mark of vaudeville professional Katie Sandwina. Since Karyn did this as a tall 82kg-er it was naturally assumed that the lighter categories would not approach her lifts. And no one ever expected any woman to clean and jerk 400lb. Such seemed impossible.

At first many thought women’s performances would never top a certain level. Each observer had his own idea of how high that would be, but the one thing they all had in common was that all would prove too low. I remember when Karyn Marshall of the United States broke the 300lb barrier. (Pictured to the right) She was well ahead of anyone else in the 1987 Worlds so many assumed she had topped out for women. This was greater than anyone else in history, topping the nearly century old Guinness mark of vaudeville professional Katie Sandwina. Since Karyn did this as a tall 82kg-er it was naturally assumed that the lighter categories would not approach her lifts. And no one ever expected any woman to clean and jerk 400lb. Such seemed impossible.

Well, just look at the records. They climbed ever higher. Even the 58kg category surpassed the 300lb jerk. In London, Marshall’s 1987 performance would have landed her in tenth place. Competition did indeed force all to rise to new heights. Marshall would later gain success with Masters lifting, CrossFit, and most courageously, in fighting cancer.

Now it is not just the women of the North Atlantic or East Bloc community that lift weights. A look at the London results shows a diverse array of nations, many of which would not have gotten into women’s lifting if the lead had not been taken by the pioneers of the 1980s.

Progress has not come solely from the athletes – a major change has occurred just recently with regard to officiating. Now every referee team will consist of four referees, three active and one reserve, rotated with each session they work. Nothing new there except that two of them now must be women. In this way any group may decently handle a weigh-in regardless of sex (only two referees are needed for a weigh-in). This will in turn mean that every nation will now have to recruit and train female referees if they want to have a better chance of having anyone selected to officiate.

In addition to that, the IWF Executive will be co-opting a female on their executive if none is elected in their own right. So now a female voice will be heard in every Executive meeting and will also have to be considered whenever lobbying is contemplated. There are a number of women serving at committee levels, which are stepping-stones to higher positions, so there are opportunities for working an apprenticeship if they desire. In national circles more women are appearing in executive positions so some of them may rise to higher positions in time. We will have to see.

With regard to coaching things have been uneven. Most women lifters still have male coaches. Some female coaches are appearing, but not as fast as desired. This may be due to the life cycles of the athletes who may want to coach. After a few years of training, mostly in their teens and early twenties, they, like their male counterparts, will need to make up for some lost time, either in a career or in having a family, or both. These will leave little time for coaching so often things end here for female lifters. They may be able to return to the sport some years later, but it is always difficult making a career re-entry as many women can attest. It remains to be seen how the coaching side will develop. Outside the sport we are seeing some female strength coaches in other weight training circles where the incumbents are still young or where the time demands may be less onerous. We will see more of them, but the degree of change is still hard to predict.

With regard to coaching things have been uneven. Most women lifters still have male coaches. Some female coaches are appearing, but not as fast as desired. This may be due to the life cycles of the athletes who may want to coach. After a few years of training, mostly in their teens and early twenties, they, like their male counterparts, will need to make up for some lost time, either in a career or in having a family, or both. These will leave little time for coaching so often things end here for female lifters. They may be able to return to the sport some years later, but it is always difficult making a career re-entry as many women can attest. It remains to be seen how the coaching side will develop. Outside the sport we are seeing some female strength coaches in other weight training circles where the incumbents are still young or where the time demands may be less onerous. We will see more of them, but the degree of change is still hard to predict.

All in all, the last 25 years have seen amazing changes with regard to women’s weightlifting. No longer a freak show or even a self-conscious or forced exercise in sexual equality it is now a respected part of the Olympic program and a legitimate athletic ambition for many girls. Women are part of the establishment of the sport now, appearing in all roles, albeit still somewhat unevenly. While this is satisfying it also forces one to wonder what the gender landscape will look like in another 25 years. Where will the women’s records be? How many female national presidents will there be? How many girls will be able to obtain sponsorships that only male athletes have much chance of getting today?

Karyn Marshall photos by Virginia Tehan (mother of Karyn Marshall) [CC-BY-SA-2.5], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 courtesy of Greg Everett and Catalyst Athletics.