Last week I looked at the similarities between accounting and weightlifting. In particular I zeroed in on variance analysis in regard to performance analysis. As with accounting I noted that most variances that get analyzed are the unfavorable ones. These demand attention because in most accounting systems it will be easy to attach blame to whoever was responsible. This also occurs in weightlifting. Errors get the most attention.

As for favorable variances, many of these are glossed over and complacency rules. “All is well, so let’s move on to the problem areas” seems to be the attitude. But is this reasonable? Is there anything to be gained from looking at what we did right?

We are told that we should learn from our mistakes. This is indeed good advice. A mistake is usually easy to spot, if not by you then by others. And we all know how eager some people are to point out our errors. Nevertheless this situation does motivate us to improve. We know what went wrong and then we can go about correcting things.

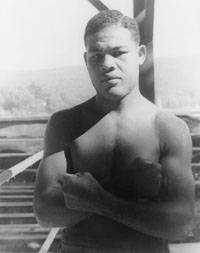

Boxers are one of the better examples of this tendency in the sport world. Alberta Sport Hall of Fame coach Kai Yip once remarked to me that you never learn anything from winning a fight, only from losing one. He pointed out the story of how Joe Louis always dropped his guard when delivering a punch. Max Schmeling, generally considered a lesser boxer, was able to exploit that flaw and handed the Brown Bomber a setback on his eventually successful quest for the heavyweight title.

Louis’s long string of wins against generally lesser opposition had made him complacent. Louis had been warned of this flaw by former champ Jack Johnson, but since there was a lot of jealousy between the first two black champs Louis was not inclined to listen to the old man’s advice. Only when his string of success ended was Louis ready to listen to the suggestion that he keep his guard up during punches. Trainer Jack Blackburn used the shock of this loss to finally motivate Louis to change his tactics. As a result Joe learned this lesson and Der Max was no match for Louis in their second meeting (KO1 for Louis).

This is all very informative but was Kai right about not learning anything when winning? I had to disagree even though I conceded that motivation to learn will usually be higher after a loss. But it is just as important to try to learn from victories. After all, you must have done something right if the gold now hangs around your neck. It then behooves us to determine what things were done right. I pointed out to Kai that ever after Louis kept his guard up and as a result reigned longer than any other champion. This was a case where someone indeed learned from winning.

This is all very informative but was Kai right about not learning anything when winning? I had to disagree even though I conceded that motivation to learn will usually be higher after a loss. But it is just as important to try to learn from victories. After all, you must have done something right if the gold now hangs around your neck. It then behooves us to determine what things were done right. I pointed out to Kai that ever after Louis kept his guard up and as a result reigned longer than any other champion. This was a case where someone indeed learned from winning.

It is good to know how well a good training plan can bring victory. Sometimes, however, winning can occur even when pre-meet training and other factors were not up to par. This is often the case in local competitions where opposition is weak. An unseasoned lifter may get the idea that whatever he did on the way to winning was acceptable and will be acceptable in future. I remember one lifter in particular who was unfortunate enough to win his first competition, despite having trained only haphazardly. It took him a long time to realize that he won in spite of his slack training, not because of it. In the meantime he wasted a lot of time and wondered why others were leapfrogging over him.

Come to think of it, ego is another factor that all too many lifters ignore but should be taken into consideration. It is one thing to win in a local garage meet, quite another when the stakes get higher. Victory may have been due to factors of which the lifters were not aware. Perhaps they won in spite of themselves, not because of their abilities. Some even forget that they wear the gold because no one else entered in the meet. They will assume they have nothing to learn since they “won.” That seems irrational but I’ve seen it happen many times.

Other factors that the lifter likes to highlight may not be the reason he won. For example, one lifter I once knew thought he was a strong squatter so that is what always enabled him to win with a big clean and jerk. I disagreed. I asked him what his best dead-stop squat was. He hemmed and hawed in answering. Well, it turned out that it was far, far lower than what his bounced squat was. In short, his legs were weaker than he assumed. He made his cleans but that depended on him getting a good bounce at the bottom. Meanwhile he had no reserve leg strength. If the bounce wasn’t enough he would power out. I told him that he would probably remain a good cleaner, but only until his patella tendons gave out one day. So he had to reassess his supposed leg strength.

In other cases a lifter does far better in one meet than he did in a previous one and the reasons are not very evident. The factors usually examined seem to be unchanged – training is similar, bodyweight hasn’t changed, etc. This is where the analysis must get very nuanced. Often the reason can be found to be one that is discounted as insignificant. Sleep is frequently such a factor. I remember two meets I lifted in only six weeks apart. I couldn’t discern much difference in my training. The only thing I could see was that I got nine hours of sleep before the better result and only six before the other. Afterwards I tried to get more sleep before meets and in training as well. That indeed made the difference. But since I was always a lighter sleeper I had discounted sleep as a factor.

In other cases a lifter does far better in one meet than he did in a previous one and the reasons are not very evident. The factors usually examined seem to be unchanged – training is similar, bodyweight hasn’t changed, etc. This is where the analysis must get very nuanced. Often the reason can be found to be one that is discounted as insignificant. Sleep is frequently such a factor. I remember two meets I lifted in only six weeks apart. I couldn’t discern much difference in my training. The only thing I could see was that I got nine hours of sleep before the better result and only six before the other. Afterwards I tried to get more sleep before meets and in training as well. That indeed made the difference. But since I was always a lighter sleeper I had discounted sleep as a factor.

Bodyweight is another factor. Training may go very well when one is several pounds over his category limit. If bodyweight has to be cut too close to competition then the lifter will be in for a surprise. Strength will be lost and performance will suffer while the lifter might not think the loss significant. This is especially true when the lifter gets older. Losing weight with no ill effects is easier when younger, less so as you age. In that case the lifter must damp down his ego and consider the effects of aging in his future training plans.

These are but a few examples of how things can be learned from winning and doing things right. For this reason determining what you did right is just as important as figuring out what went wrong.

Photos 1 & 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Joe Louis photo courtesy of Carl Van Vechten [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.