It sounds silly, I know. We’ve all heard people say, “I’m not fat, I’m just big-boned.” Cue the eye rolling and the shake of your head. Big bones are just a myth, right? Well, maybe not. A 2011 study found that bones really can predict those prone to obesity and to becoming overweight. Wider femur (thigh bone) shafts are very likely the result of bearing the excess weight of someone who is overweight or obese.

Now, a team of researchers from the UNC School of Medicine has found that exercise can burn the fat in bone marrow and that doing so improves overall bone health. The study, published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, also suggests obese individuals – who often have worse bone quality – may derive even greater bone health benefits from exercising than their lean counterparts.

“One of the main clinical implications of this research is that exercise is not just good, but amazing for bone health,” said lead author Maya Styner, MD, a physician and assistant professor of endocrinology and metabolism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “In just a very short period of time, we saw that running was building bone significantly in mice.”

THERE IS FAT INSIDE YOUR BONE MARROW, AND EXERCISE CAN HELP TO BURN OFF THAT FAT.

Mice were divided into four groups: low-fat diet, low-fat diet plus exercise, obesity diet, and obesity diet plus exercise. Although research in mice is not directly translatable to the human condition, the kinds of stem cells that produce bone and fat in mice are the same kind that produces bone and fat in humans.

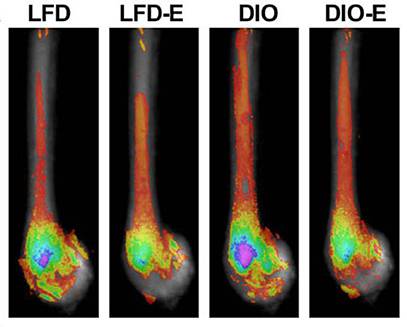

CT scans of the mice’s bones revealed that exercise helped to reduce bone marrow fat content. Within weeks of beginning training, the mice on both low fat and obesity diets saw an improvement in their bone quality.

Composite CT scans of mouse femurs are shown. LFD-E refers to low-fat diet plus exercise. DIO-E refers to diet-induced obesity plus exercise. Red, yellow: less fat in bone. Green, blue, and purple: higher fat amounts. Exercise dramatically reduced bone fat. Source: M. Styner, et al

The stem cells that produce new bone and fat cells in humans are very similar to those found in mice. This study may point to a new way to improve bone health. By engaging in exercise (in this case, running), it could be possible to burn the fat content in bone marrow, potentially stimulating the released energy to produce new bone cells. However, until doing further studies, scientists aren’t entirely certain how burning bone marrow fat leads to healthier bones.

The research leaves a few lingering mysteries. A big one is figuring out the exact relationship between burning marrow fat and building better bone. It could be that when fat cells are burned during exercise, the marrow uses the released energy to make more bone. Or, because both fat and bone cells come from parent cells known as mesenchymal stem cells, it could be that exercise somehow stimulates these stem cells to churn out more bone cells and less fat cells.

More research will be needed to parse this out. “What we can say is there’s a lot of evidence suggesting that marrow fat is being used as fuel to make more bone, rather than there being an increase in the diversion of stem cells into bone,” said Styner.

But marrow fat, being encased in bone, isn’t easy to study. The team’s new research represents a leap forward not only in understanding bone marrow fat but also in the tools to study it.

The group’s previous work relied on micro CT imaging, which requires the use of a toxic tracer to measure marrow fat. In the new study, they took advantage of UNC’s 9.4 TMRI, a sophisticated MRI machine of which there are only a few around the country. Using MRI to assess marrow fat eliminates the need for the toxic tracer and allows highly detailed imaging of living organisms.

“If we want to take this technique to the human level, we could study marrow fat in humans in a much more reliable fashion now,” said Styner. “And our work shows this is possible.”

The team also developed techniques to perform a much more detailed assessment of the number and size of fat cells within the marrow and even examined some of the key proteins involved in the formation and reduction of bone marrow fat.

Styner is now working with collaborators to adapt these methods for studying the bone marrow dynamics that might be at work in other conditions, including anorexia and post-menopausal osteoporosis.

Reference:

1. Maya Styner, Gabriel M Pagnotti, Cody McGrath, Xin Wu, Buer Sen, Gunes Uzer, Zhihui Xie, Xiaopeng Zong, Martin A Styner, Clinton T Rubin, Janet Rubin. “Exercise Decreases Marrow Adipose Tissue Through ß-Oxidation in Obese Running Mice.” Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2017.