Right from the start of physical culture a strong midsection has been prized. From the six-pack of Eugen Sandow to books like Enter The Kettlebell saying, “It is no coincidence that since overhead presses have fallen out of favor, manly Farnese Hercules torsos with powerful shoulders and midsections have given way to small, feminine waists and large pecs.”

Back in the 70s and 80s bodybuilding ruled the roost. It wasn’t unusual to see guys with ripped six-packs doing hundreds of reps per day to keep their abs sharp. The problems came when sports teams adopted the same training methods the bodybuilders were using in the mistaken idea that looking tough was the same as playing tough. And while the Eastern Bloc countries forged ahead with traditional strength and sports training models, the West got lost in a fog of machines, high reps, and isolation training in an effort to make our athletes look the part.

I’ve seen guys who look like action figures who couldn’t hurt a fly with a punch and I’ve seen plenty of guys who look like tubby weaklings who can throw down with the best of them. So what’s the thing that causes this difference?

It’s the core.

The role of the core is to stabilize the spine. That’s it. The moment you go into flexion or rotation you’ve lost core control and are operating sub optimally. This is why good coaches will go on about training posture so much – when you learn to perform with good posture your spine is stable. The problem with this is that every step, every arm swing, and every turn of the head is actively seeking to perturb your core. The harder and faster you expect to perform an action, the stronger and stiffer your core needs to be to maintain posture.

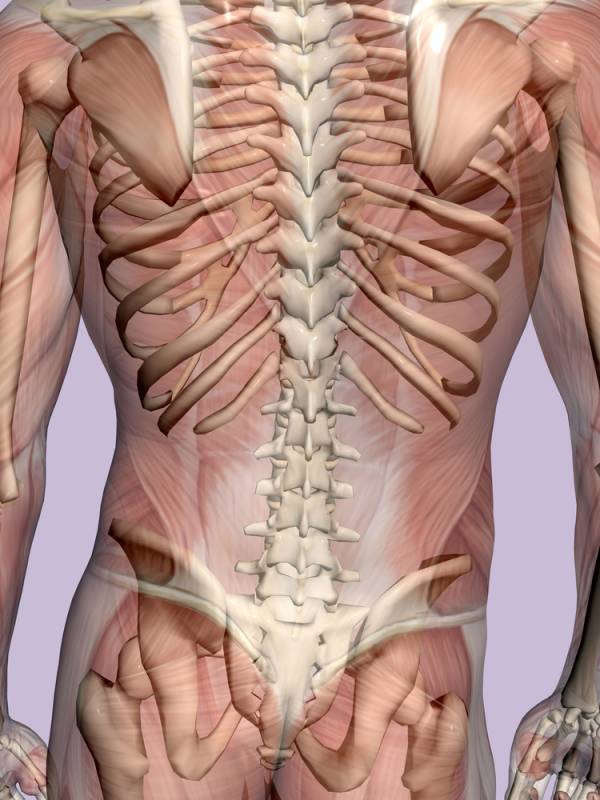

What Is the Core?

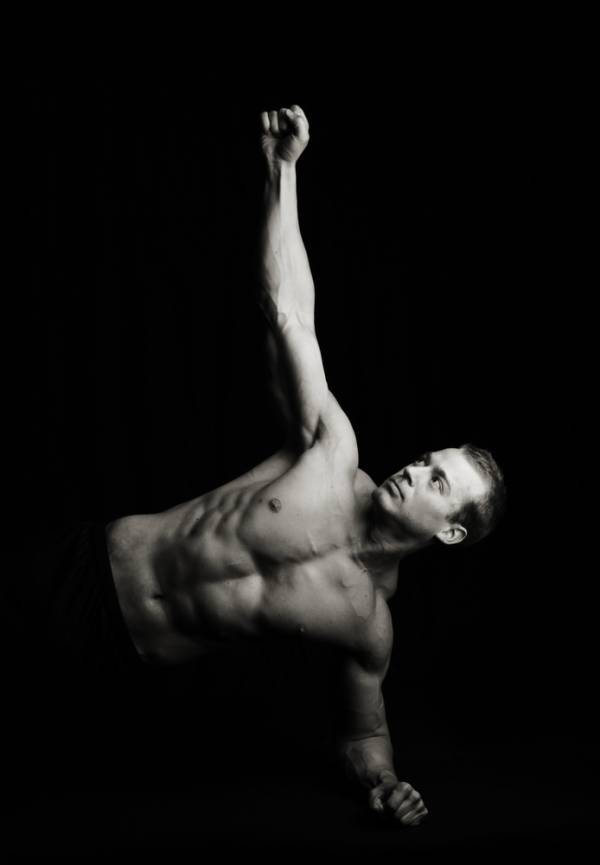

That may seem like a fairly simple thing to create, this development of midsection tension during an action, but when you start breaking down what is involved you’ll see just how far ranging the “core” can be. From a fighting stance, as you throw a punch, everything that prevents you from twisting or turning can be considered a core muscle.

The lower leg needs to be braced and strong to prevent the foot rolling in, which will cause the knee to cave in upstream. Likewise the hips need to be strong to prevent the exact same thing. The muscles that surround the spine – from multifidus to quadratus to the latssismus dorsi – all act to stiffen and stabilize the spine during such actions. Of course there is also abdominal involvement, too. So pretty much the core can be thought of as all the muscles below head height.

The Problem With Isolation

And that’s where we all went wrong with isolated training. One of the keys to performance is that muscles learn to work together and deliberately training them to be used individually leads to problems when you ask someone to take that gym built strength and turn it into sports performance.

This is one of the main reasons that people often report the mysterious “what the heck” effect when beginning with kettlebells. Most people begin with a single kettlebell. Imagine what is going in inside your body when you hold a kettlebell in the rack position or overhead only on one side? The opposing side of your body is going through a tremendous amount of work to keep your spine stable. Research on the one arm swing shows that as much as 180% MVC (maximum voluntary contraction) occurs on the opposing side (through external obliques and glute medius) to keep the spine stable. And when it comes time to take the playing field that strength gained from all the hidden core work you’re doing will pay off.

Ways to Develop a Strong Core

Isometric Holds – To develop a strong core, I would start with isometric holds such as the plank and side bridge. Both teach the essential elements necessary for good core stability in a very controlled manner. Remember – if you can’t do it in an easy progression, you’re certainly not going to manage it under a heavy bar or while trying to throw someone in a fight.

Crawling – The next step would be adding in some crawling. Crawling is still fairly controlled and has the added benefit of gravity acting on the midsection, so you can feel whether or not you’re doing the right thing. We also have action with both the arms and the legs that needs to be counteracted.

Single-Sided Training – I would then move to single-sided training. This can be a kettlebell or dumbbell, and exercises like the suitcase deadlift or even single-leg deadlifts. I would also add in movements like the front or back lever as well as all strength work on rings or TRX. Speed of movement here is still very deliberate and methodical, as we won’t introduce speed until the next stage.

Throwing – The final step would be the integration of speed and power into this progression which could be in the form of throwing, such as with medicine balls, or by simply practicing specific sports skills.

The main thing to remember is that the early stages of training – with static, isometric holds and then crawling – are break-in stages and merely a stop on the way to developing real core strength. Don’t neglect spending time there though, or even returning to it yearly during transition phases, as the gains made will serve you well long term.

Don’t fall into the trap of neglecting your core work – athletes have known it’s the hidden secret of performance for many years and it’s time the rest of us stopped skipping it altogether and then wondering why our own performance suffers.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.