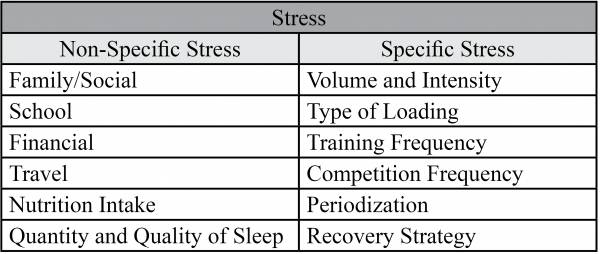

Training really comes down to one thing: stress management. In the gym you add stress to try to push your body to a new level. Outside the gym, you do everything you can to alleviate the stress imposed in the gym.

When you achieve the right balance, you get what is called super-compensation, or training adaptation. When it’s wrong, you get over-reaching, which could make you too fatigued to train hard enough to stimulate change. If you go even further down the wrong track, you end up with over-training, which can lead to a near total system shut down.

Emotional stress wreaks as much havoc on your body as physical stress.

Stress Is Stress

Most people only look at the training performed in the gym or on the track when assessing levels of fatigue. However, the body doesn’t differentiate between mental, emotional, or physical stress. As far as the systems of the body are concerned, stress is stress.

That time your boss dropped a big pile of work on your desk that had to be done before you left the office was just as traumatic for your body as a max effort squat day. So the last thing you should be doing if you’ve just had one of those days is head to the gym and max out. This seems counter-intuitive. When you have a bad day, it’s natural to want to take out that aggression in the gym and let off some steam. But when you do, you’ve essentially had what amounts to two max effort sessions in the same day, as far as your body is concerned.

From Joel Jamieson’s, Certified Conditioning Coach manual.

Stress in the Gym

Before we get to the actual stress-management solutions you can accomplish at home, let’s discuss some of the problems with most gym training models. Like it or not, anaerobic training produces the same type of energy seen in our fight-or-flight responses. It has to, because we need it to help us run away from predators for survival. But all that energy being produced so quickly has a damaging effect on your body. It is highly inflammatory, just like your stress-filled days at the office.

This is where movement quality comes into the picture. Movement quality has both a physical and a mental component. The energy systems and connective tissue are the bodily components, but they are driven by the autonomic nervous system and motor control, which are managed by the brain. The role of the nervous system is to perceive threat through the use of all of your senses and is linked to motor output functions (such as speed and power), and these functions are linked to your motor control.

The sympathetic nervous system drives extension-based postures and activities, such as running and jumping, as well as most lifts. In other words, it is your fight-or-flight posture and supports higher force activities. However, as motor control is based on threat perception, an over use of both this system and these postures results in negative changes in motor control. These changes to motor control lead to higher levels of fatigue. Those higher levels of fatigue lead to less movement variability – you become more robotic – and that leads to more injuries. In other words, spending too much time in your fight-or-flight postures performing high-force activities leads to greater likelihood of injury. What can you do to fix all this?

Protect Your Body From Threat

The body perceives new activities as a threat. This applies whether it is a new load, new exercise, or a new distance – they will all be viewed the same way by the body. That drives you straight into your fight-or-flight system and instantly turns what is meant to be an educational session into something that is perceived by the body to be a maximum effort. So we need to slowly introduce new stressors to training. This is precisely why you shouldn’t learn the barbell snatch on day one in a gym. There are just too many things that are new if you’re not familiar with barbells and weightlifting.

As movement quality improves at each level, the first step is to add load. Once that step has stagnated then you can seek to add complexity – perhaps going from a hang power snatch to a power snatch. Once that has settled you can seek to add fatigue by adding volume before starting in on the next progression. The basic format is to add intensity, then complexity, before adding capacity.

Balance Your Stress Level

But don’t forget, new movements cause stress. To counteract all that stress you need training methods that soothe the body and allow your system to reset. For example, a day where you learn new moves should finish with an easy aerobic cool down to return the body to a suitable resting state that is responsive to training. Just as your warm up should prepare you for stress, your cool down should ready you to absorb the stress. And that is best done with a settled mind and body.

But all that could change if you chose the wrong recovery format. I’ve known beach volleyballers who weren’t great swimmers choose to go swimming for recovery the day after a tournament. Unfortunately, their bodies didn’t agree that it would be easy, so what should have been an easy session smashed them further. Walking in cool water might be a great choice for you, but unless you’re actually a good swimmer there’s not much chance that swimming will be a good recovery session.

Remember, if your body perceives a threat then it will react as if under threat with that same fight-or flight-response. Next thing you know, you’ve turned your recovery session into another hard session and your system will be depressed even more.

Is swimming the right active recovery for you? That depends. How well can you swim?

What Activities Are Best?

Some activities lend themselves better to recovery than others. Here are three I recommend:

Flexion-Based Postures: The parasympathetic nervous system features flexion-based postures. Activities like cycling and rowing make for far better choices than running, as it is extension based. Have you ever wondered why yoga has such a settling effect on the body? All that time spent in downward dog, a flexion-based posture, has a deep-seated link to promoting calmness within the body and mind.

Breathing: The quickest, cheapest, and easiest way to influence the parasympathetic system is to focus on respiratory function. Methods such as FMS have had highly successful results from exercises as simple as crocodile breathing. I have had clients who have found huge improvements for shoulder pain after five minutes of targeted breathing practice, combined with education about how to recognize and manage signs of stress.

Meditation: My good friend Chris Holder has done some interesting studies on using guided meditation to reduce stress among his Division 1 athletes. He and his colleagues found that following a daily guided meditation made up for poor sleep and dietary habits often seen in college athletes burning the candle at both ends. In my experience, the best time to perform this is before bed so that sleep quality is enhanced. Omvana is a free app that guides you through a twenty-minute series designed to relax the body and mind.

Train and Recover Smart

Once you’ve got your recovery figured out, the final step is monitoring training intensity and frequency. Most people can’t handle more than two or three hard sessions per week, and the days between should be filled with active recovery to stimulate the system, not further deplete or stress it.

The goal of training is to improve the body, not test its limits. Focus on adding guided meditation and focused breathing work, as well as aerobic recoveries and cool downs, and you will be surprised at how much better your body feels.

More on Stress Management:

- Hack Your Stress Before It Hacks You

- The Ups and Downs of Cortisol: What You Need to Know

- Diaphragmatic Breathing Reduces Exercise Induced Oxidative Stress

- New on Breaking Muscle Right Now

Photo 1 courtesy of Jeff Nguyen/CrossFit Empirical.

Photo 2 courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photography.