There is no doubting the need to acknowledge that men and women deserve the same opportunities in sports, fitness, and by extension, their physical training. However, refusing to address the issues that differentiate men and women is not helpful either. So, let’s take an objective look at the functional differences in male and female populations and the respective biomechanical influences in strength training.

Antonio Squillante – Don’t Simplify Biomechancial Differences Between Men and Women

Biomechanics is a science, and like any other science, it is meant to provide answers. Quite a pragmatic approach, considering the complexity of Newtonian mechanics. Above and beyond sophisticated trigonometry functions that reduce tangible reality to a series of mathematical equations, the mechanics of the human body – as the prefix “bio” in biomechanics (“life” from the Greek “bios”) suggests – is much more than just angles and levers.

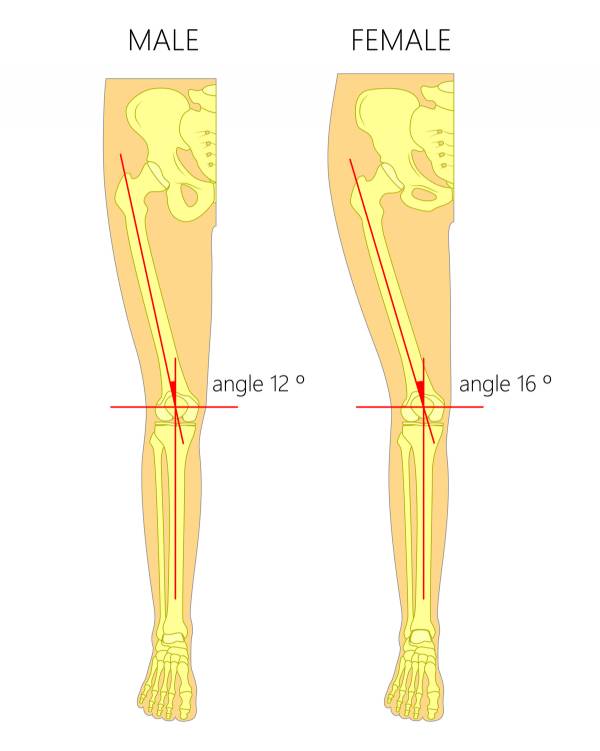

Anatomy of a healthy human male and female knee joint with Q angle between femur and tibia, anterior or front view of the leg

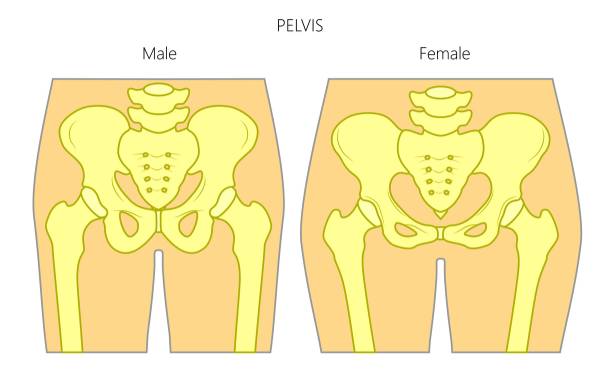

Sadly, when it comes to strength training, biomechanical differences between male and female athletes are often simplified in terms of different response of the lower extremities under load. A difference in Q angle, a geometrical feature that affects lower body mechanics resulting in a tendency for the knees to collapse medially. The Q angle is the angle defined by the femoral shaft and the lower extremity mechanical axis, the line connecting the geometrical center of the coxofemoral joint with the line of gravity passing vertically through the ankle. A diviance of approximately 10 degrees that affects the overall mechanics of the lower body in weight-bearing situations.

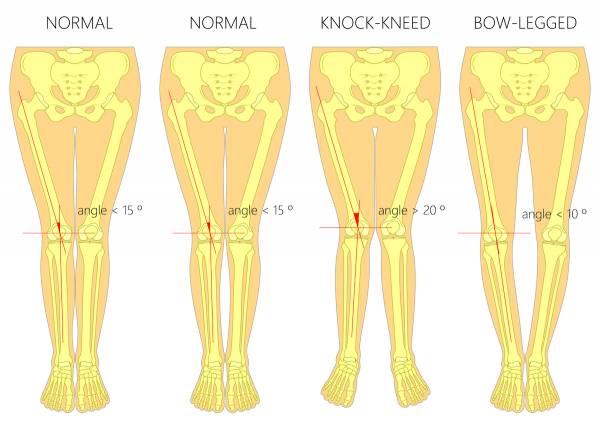

Based on the geometry of the hip complex in relationship with the femoral shaft, for any given degree of hip flexion under load corresponds a certain degree of medial deviation at the knee, a consequence of hip adduction and internal rotation, a situation know as dynamic knee valgus. The word dynamic, in this scenario, means “under load” namely “in movement” to distinguish it from a pathological situation of knee valgus that represents a relatively common paramorphism.

It would be quite simplistic, however, to reduce movement to a geometrical combination of complementary angles. Kinetics and kinematic of the lower extremity corresponds to a specific pattern of muscle activation. Hip flexion/internal rotation is, in fact, necessary to recruit those muscles responsible for counteracting gravity, such as the glut max and mid, and even more so the hamstrings.

With no “medial shift” of the lower extremity there would be no pre-activation of the posterior kinetic chain resulting in more force – both internal and external forces – applied upon ligaments and tendons surrounding the knee joint, ultimately resulting in a situation of stress that can lead to mechanical failure (failure equals injury, more likely than not involving the anterior cruciate ligament).

Despite the fact that female athletes display, on an average, a greater Q angle when compared with their male counterpart, this “geometrical” difference does not represent “per se” the source of potential differences in strength training. Lack of strength – eccentric strength, more than anything else – in the muscle responsible of limiting excessive dynamic knee valgus represents the most significant factor to take into consideration when designing strength training programs for female atheles.

Female athletes will display a moderate amount of knee valgus under load: this mechanical behavior is a consequence of a different geometry of the lower extremity and I can’t be “corrected”. It is necessary, therefore, to develop eccentric strength in the posterior kinetic chain so that movements can be safely and effectively performed while respecting individual differences in lower body mechanics: glut max and mid eccentric strength, hamstring to quadriceps strength ratio, and ultimately, proper movement mechanics are the three most important aspects that need to be addressed when working with female athletes.

Giulio Palau – Everyone Should Know How to Hinge

One of the most significant biomechanics differences between male and female populations is the Q angle. Q angle refers to the relative angle between the patella and the anterior superior iliac spine (the lateral bony edge of your hip). Women tend to have a greater Q angle due to the evolutionary adaptation of having wider hips. The functional consequence of this fact is a tendency for the knees to shift medially during hip flexion.

This will typically result in adduction and internal rotation of the femur during functional movements that require hip flexion (a fairly comprehensive category). The structural consequence of this biomechanical feature tends to manifest in what is referred to as “quad dominance“. This simply refers to a strategy of deriving strength and stability from the anterior structure of the hip as opposed to the posterior chain, further compounding the medial knee shift during movement. This is presumed to be the primary reason why ACL injuries are so much more common in female athletes.

Of course, the relative Q angle will vary with each individual, and many female athletes and clients will be able to move and stabilize using their posterior chain. But the phenomena of the Q angle is well documented and should be considered to prevent possible injuries and to move more efficiently. One simple way to mitigate these risks is to strengthen the core muscles. This applies universally. Q angle or not, healthy hips need a strong foundation.

In order for the hip muscles to generate force and apply it effectively, the core musculature must be able to stabilize the torso for the efficient transfer of forces. You must be able to dissociate movement of the spine from movement of the hips. More specifically, emphasizing the posterior chain to train positions of external rotation and more hinge based movements will take stress off the knees.

There is a continuum between squat and hinge patterns and each individual will have different positions where they are stronger. That being said, the posterior chain can be emphasized by minimizing dorsiflexion during hip flexion. This will translate the hips back during flexion and will result in loading more of the posterior musculature.

There’s nothing wrong with squatting and dorsiflexion, but everyone should also know how to hinge. Becoming more comfortable with the hinge and strengthening the posterior muscles will help mediate the structural risks of a greater Q angle. Again, Q angle or not, male or female, if you observe a medial knee shift under load, take some time to address some of these protocols. Injury prevention is a lot easier than injury rehabilitation.

Ted Sloan – Greater Mobility Can Mean Greater Risk of Injury in Strength Training

There are several aspects to training a female versus a male athlete that must be emphasized and others that change almost daily that must be taken into consideration. Female athletes tend to be naturally more flexible than men and especially at certain points during a monthly menstrual cycle, this can be affected to an even greater extent. As a result, when mobility is at its greatest, a female is often at their greatest potential risk for injury when strength training.

The most often mentioned aspect of these differences is the Q-angle. As mentioned by my colleagues, this angle opens up the alignment of the knees to the point that athletic activity can potentially become risky, if the athlete is not trained to jump and decelerate their bodies properly on the field.

This can be taught through strength, skills training and lots of practice. During strength training, understanding of the Q-angle and how to better control the translation of the knees into valgus can be practiced, however, with certain strength movements, valgus can be a necessary evil in order to help produce more strength through extra activation of hamstring and gluteal musculature.

The Q-angle manipulates the contribution of the posterior chain musculature to the point that the quadriceps can become the stronger and more dominant muscle group. As a result, teaching specific exercises, such as a hip hinge, can create a better understanding of jumping and lifting mechanics. Further care to create extra strength in the hamstrings, glutes (butt muscles) and lower back is vital.

Genu Valgum (knock-kneed) and Genu Varum (bow-legged)

Valgus prevention is an important attribute to focus on for both males and females, but the increased Q-angle can make it a more challenging task for a female athlete, especially when taking the potential for extreme mobility at certain times of the month.