Where I live, we have a chain of “functional” gyms opening. Like most things in the fitness industry, it has all been done before. In this instance, it is circuit training, a program that was developed by R.E. Morgan and G.T. Anderson at the University of Leeds in England in 1957.

If I lined up 20 fitness professionals and asked them to define what “functional training” is, I would bet that I would get 20 different responses. The buzzword is used to describe pretty much everything in the industry: functional fitness is done with functional exercises with functional movement, functional equipment, and in functional footwear. Then you can rehydrate with your functional water and recover with functional nutrition. If I read it one more time to sell me something, or if someone tells me they are doing anything “functional” in the gym again, I may respond a little like Master Ken’s “hurticane.”

The term itself isn’t even a new thing. It was used by Edith Buchwald, a physiotherapist who wrote about “functional training” in The Physical Therapy Review in 1949. That’s a long time before the term became fashionable like it is now. But what the hell does it mean?

- Function has been defined as “an activity that is natural to or the purpose of a person or thing.”

- Wikipedia will tell you that “functional training is a classification of exercise which involves training the body for the activities performed in daily life.”

- Elsewhere, we find that “functional movements are based on real-world situational biomechanics. They usually involve multi-planar, multi-joint movements which place demand on the body’s core musculature and innervation.”

With that in mind, let us look at the “functional training” tribes.

The Rehab Tribe

Functional training has its origins in rehabilitation, where physical therapists select exercises for their injured patients. The exercises closely mimic the movements and patterns those patients need to be able to perform at home or at work, and are meant to correct movement disorders, dysfunction, and asymmetries, or rehabilitate from injury.

This basis of training saw us go down the rabbit hole. People started using all sorts of unstable surfaces (dura discs, BOSU balls, swiss balls, wobble boards) and contraptions like Pilates reformers, which are meant to improve core and lower back function. Training on unstable surfaces can be extremely helpful for someone to improve body awareness, proprioception, balance, core function, and stability (motor control).

Fortunately for those of us who enjoy YouTube fail compilations, this type of training made its way to the mainstream gym environment. Understandably, it’s copped a lot of flak. But only because it hasn’t been used in the goal-centric way specialists use it.

Slapping the word “functional” on an exercise does not make it so. [Photo credit: Gregor | CC BY 2.0]

The Old-School Strength Tribe

One of the biggest criticisms of the rehab perspective when it comes to “functional training” is that it tends to overlook the value of traditional principles of strength training. The general consensus with this group is that a stronger muscle is a more functional muscle. They generally advocate multi-joint exercises, done while standing.

The problem is that function can vary from joint to joint, and exercises done seated can be extremely functional, as Mike Boyle discussed some years ago. He discusses the interesting paradox that has come full circle where targeted work on the deep abdominals, hip and scapula stabilizers, if neglected, can be detrimental to an athlete’s performance.

Who’s Got It Right?

Science does show that training on labile and unstable surfaces for the most part is a futile pursuit for developing strength and power. But strength training advocates fail to recognize two things. First, all strength training is underpinned by good quality movement. Second, strength has neuromuscular balance and control prerequisites to it, and when these are dysfunctional even our strongest people end up in pain. So a stronger muscle is not always the most functional. Just look at the strongest athletes on the planet—gymnasts and Olympic lifters—and you will find they all have great quality movement.

Conversely, what the rehab tribe fails to realize is that you must restore normal movement patterns by actually learning normal movement patterns. At some point, many rehab professionals have missed the part where their job is to get people off the reformers and away from unstable surfaces into normal movement patterns. The truest criticism of the rehab tribe is that their adherents spend all their time on “prehab,” and no time actually lifting heavy stuff and getting strong.

The Modern Gym-Goer and the Search for Functional

Most gym-goers believe that the functionality of their workout comes from working the battle ropes, hitting a tire with a sledgehammer, using a suspension training system, swinging a kettlebell, and doing multi-planar, multidirectional exercises. This current form of functional training attempts to incorporate as many variables as possible (balance, multiple joints, multiple planes of movement), increasing the complexity of motor coordination and flexibility.

Often, we see people doing functional training also trying to mimic the skill of their chosen sport. The irony is this clearly violates the SAID (specific adaptation to imposed demands) principle, specificity and skill transfer, especially if you have any understanding of motor learning. Your nervous system gets good at what you do. When it comes to motor learning and skill transfer, trying to mimic everyday movements does not necessarily directly carry over to everyday movements, and trying to mimic your sport also doesn’t necessarily transfer to your sport. Only doing what you do daily does that, and only playing your sport does that. In other words, actually doing the thing is the best way to get better.

It’s called the principle of specificity, not similarity.

As the late Arthur Jones once said: “Add resistance to a skill and it becomes a different skill; add enough resistance to a skill and it becomes an exercise.”

The True Essence of Function

Training is only truly “functional” if it helps the person function better, is individualized and is goal-focused.

From my perspective, any exercise that helps one achieve their movement goals, or improves their quality of life could be considered functional. I certainly don’t think it is up to personal trainers to tell clients what is functional and what is not, even though that is often what we do. In a sports-specific environment that may be different, as we have to define what the athlete’s key performance indicators are and address those specifically. But even that will change from person to person.

If I have someone in chronic pain, maybe having them balance on one leg and play letter ball with me is functional. Why? Because that external focus (just like those in mindfulness exercises) takes the mind outside of the body to decrease the brain’s map of pain. It helps my athlete become fully present and focused on having fun, balancing, their hand/eye coordination, and calling the letter out to me as they catch the ball. And for that moment in time, they may be completely out of pain.

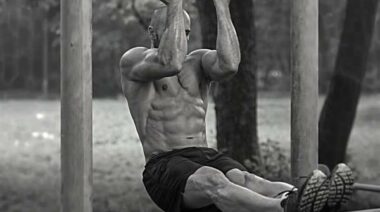

Whether you consider the rope climb functional depends on your needs and goals.

If I have an athlete competing in an overhead sport who is in pain, I might have to do very specific and isolated scapula work to improve thoracic mobility and scapular stability. That would fly in the face of the strength tribe’s tenets of functional training, that say that it’s only functional if it is done standing, is multi-joint and involves progressive overload.

If I have another athlete that prefers to do machine-based exercises, they are more likely to stick to that than smashing out a battle rope, burpee and kettlebell swing HIIT session. Training can only be functional if you’re going to do it. Someone’s ability to stick to your program makes it more functional because they are doing something that enhances the quality of their life and meets their goals.

A friend of mine, who is a coach for a VFL team in Melbourne, was asked to improve a player’s ability to mark (jump and catch) a football. Everyone was amazed to see the player marking a ball in the following months and congratulated my friend on a job well done for getting the player “fitter and stronger” to mark the ball. You know what my friend did? He had the player doing vision drills because the player’s eyes couldn’t track the ball properly. Is that not functional training?

If an athlete walks in my door and wants to get bigger biceps so he can attract a partner to marry and reproduce, who am I to say that’s not functional?

Dr. Mel Siff sums it up nicely:

“It would probably be preferable not to refer to any specific exercises as “functional” but instead to refer to exercises that enhance “functional” competence in a given sport, task, or context. Thus, the tools or the process involved may be any training means whatsoever (functional, non-functional, restorative, recreational, or whatever may be desired at any given time)—the important issue is whether the particular exercise program … produces an outcome that is “functional” (i.e., provably enhances performance in a given motor action or sport).”

Drop the Label and Just Go Train

The term “functional” has become an elitist word used to sell memberships, equipment, and training fads. You can see over the years it has taken many different shapes and forms. Whilst I love the current form of functional training, I think it is about time we started to respect what everybody does. Whatever someone does, wherever they are in their journey, whatever training modality they choose to do, the main thing is that they are actually doing something and improving their quality of life and working towards whatever their goals are—not yours.

By coining things in this fashion, it often means that we can emphasize exercises and movements that may in fact provide benefit for optimal function, performance and health. The way I see it, if you feel like doing something and it meets your goals and improves your life, go and do it. But for fuck’s sake let’s drop the redundant term and stop calling training “functional,” and just get back to training.

More debunking the buzzword: