To add the evasive ten pounds of sleeve-stretching muscle it’s best to use a time proven nutritional method – carb cycling. High performance strength and physique athletes have used carb cycling for decades to optimize athletic performance and body composition.

Gaining muscle requires a caloric surplus, potentially covering those shredded abs, so it’s time to ditch the old standby of bulking with unrestricted diets. There’s a better way. By maximizing the anabolic power of insulin with carb cycling, it’s possible to shred fat and build muscle simultaneously.

Once you’ve got your nutrition dialed, check out Part Two: The Lifting Program.

What is Insulin?

Insulin is an extremely anabolic hormone that will make or break your physique. Too little and you’re doomed to flat muscles, poor recovery, and pre-shrinking your affliction t-shirts. Too much and you’ll resemble the Michelin Man and suffer from myriad health problems.

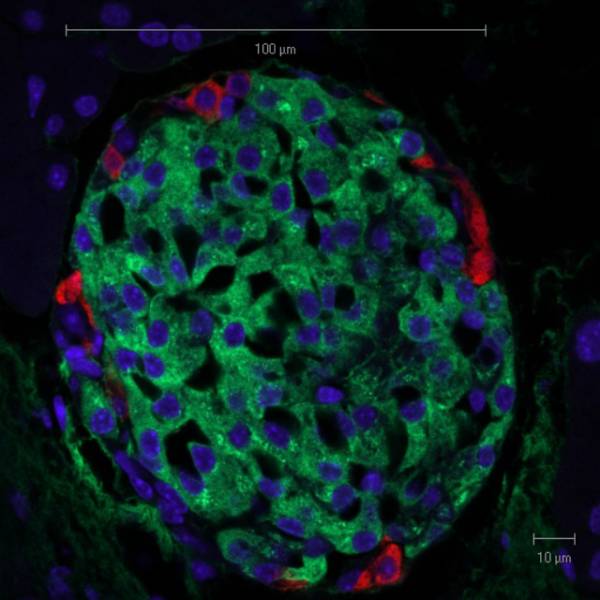

Insulin is a hormone made in the pancreas, an organ located behind the stomach. The pancreas contains clusters of cells called islets. Beta cells within the islets store and release insulin into the blood. Insulin plays a major role in metabolism. The digestive tract breaks down carbohydrates into glucose, but its with the help of insulin that cells are able to absorb glucose and use it for energy.5

Insulin-producing beta cells, in green, on a mouse pancreas islet. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Insulin regulates nutrient entry into muscle cells. When insulin is seldom elevated, then muscle growth related benefits won’t occur. A higher carbohydrate intake when your body is increasingly sensitive, such as post-workout, promotes carbohydrates to initiate tissue repair and set the stage for muscle growth. Conversely, when the body is not sensitive to carbs and you’re crushing the pasta buffet, excess carbohydrates will be stored, building some brand-new layers of blubber on your waistline. Through proper timing and fluctuations, carbohydrates will be under your control, allowing the body to strip rolls of fat and build slabs of muscle.1

Fuel Use During Exercise

Muscle tissue glucose uptake is stimulated by insulin, which triggers the migration of glucose and amino acids to muscle cells, promoting protein synthesis. Muscle contractions increase the facilitated diffusion of glucose into muscle cells even further, promoting greater insulin sensitivity. Simply, when glucose is present in the blood the body will utilize it as an energy source over stored fuel – an ideal recipe for building muscle mass.

Conversely, when carbohydrates aren’t readily available and fat or protein is the primary source, higher levels of the hormone glucagon combined with lower levels of blood carbohydrate can lead to a higher rate of fat burning.2 Through manipulating your source of readily available fuel, different energy substrates can be used as fuel for exercise.

Carb Cycling

Carb cycling uses the manipulation of insulin to burn fat and maximize lean muscle gains. In this case two separate days of eating will be utilized: high-carb days and low-carb days. Resistance training days are high-carb days, providing additional fuel to maximize the anabolic response and muscular recovery. Recovery and conditioning days are low-carb to shred stored body fat and increase insulin sensitivity, both of which improve nutrient utilization on high-carb days.

Caloric Needs

Body type and activity level are used to determine your caloric need and macronutrient requirements. Yes, conquer your fear of math. It’s time for the numbers. Being an intelligent Breaking Muscle reader it’s safe to assume you’re at least moderately active. If you’re not, then stop making excuses and go exercise. Using The Essentials of Sport and Exercise Nutrition by John Berardi and Ryan Andrews, moderately active individuals are quantified as performing three to four workouts per week.3 These individuals should multiply their bodyweight in pounds by eighteen to twenty to get a caloric range.

Example 1:

A 160-lb. male would be: 160×18 = 2880; 160×20 = 3200

The caloric range would be 2,880-3,200 kcals per day.

Example 2:

A 185-lb. male would be 185×20= 3,700; 185×22= 4070 kcals per day.

The caloric range would be 3,700-4,070 kcals per day.

More active? No sweat, for very active individuals (five to seven workouts per week) ramp up the calculations and multiply bodyweight in pounds by twenty to 22 to get the caloric range.3

The Breakdown

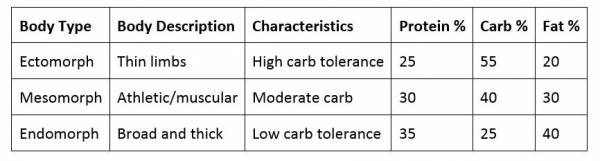

Calories provide the full gas tank, but the proper macronutrient breakdown provides premium quality to hasten your mass gains. To best determine caloric needs an analysis of your somatotype (body type) is beneficial. Although you’re not solely one somatotype, having a solid idea provides valuable insight to characteristics such as carbohydrate tolerance, metabolic rate, and even physical activity preference.

Example 1:

A 160-lb. male with an ectomorph body type consumes 2,880-3,200 kcals per day. Using 3,000 kcals per day the macronutrient breakdown would be as follows.

Protein: 3,000 x.25 = 750 kcal % 4 kcals/gram = 188 g Protein

Carbs: 3,000 x.55 = 1650 kcal % 4 kcals/gram = 412 g Carbs

Fat: 3,000 x.20 = 600 kcal % 9 kcals/gram = 67 g Fat

Example 2:

A 185-lb. male with a mesomorphic body type consumes 3,700 -4070 kcals per day. Using 3,900 kcals per day the macronutrient breakdown would be as follows.

Protein: 3,900 x.3 = 1170 kcals % 4 kcals/gram = 292 g Protein

Carbs: 3,900 x.4 =1560 kcals % 4 kcals/gram = 390 g Carbs

Fat: 3,900 x .3 = 1,170 kcals % 9/kcals/gram = 130 g Fat

Low-Carb Day

On low-carb days take 75% of the suggested carbohydrate intake to calculate needs. This number is highly variable based on carb tolerance. If you’re over 15% body fat, make this number 50% and calculate needs.

Example 2:

A 185-lb man would taper down carbs by 25% on low-carb days. High-carbohydrate days use 390 grams of carbs per day. Multiply that 390 x.75 to find the low-carb amount of 293 grams of carbs per day.

Nutrient Timing

Nutrient timing is based on the ideas that certain nutrients are maximized during various times of the day. For example, carbohydrate tolerance is higher after exercise because muscle contractions increase the facilitated diffusion of glucose into muscle cells, increasing uptake. At no other time during the course of the day can nutrition have such a profound impact on physique development and recovery as the body is ready to shift to an anabolic state with proper nutrition. Through fluctuating carbohydrate intake you can maximize the post-workout hypersensitivity to insulin and add slabs of muscle, while preventing excessive fat gain by keeping carbs low on off-days.

Considerations

“Help, I can make faces with my rapidly growing belly!”

Don’t sweat it. I’ve got a solution. Drop your carbs by another 25% on low-carbohydrate days. Consider adding some additional HIIT or finishers after two or three workouts per week.

“Dude, the scale isn’t budging. In fact, I’m losing weight!“

First, take bi-weekly measurements such as seven-site skinfolds and circumference measurements to track body composition. It’s possible you are losing weight in the form of water and fat, but still gaining muscle. Second, add an extra 200 calories to the diet. This can be as simple as a protein shake with a tablespoon of olive oil for healthy fats and protein. Considering tapering conditioning work and track your calories for a few days.

Wrap Up

“The two conditions for muscle growth are metabolic sensitivity and nutrient optimization. The first condition is satisfied in the post exercise interval because your muscles are ready to begin the recovery process. For nutrient optimization you must consume the nutrients necessary to drive recovery (4).” – John Ivy, Ph.D and Robert Portman Ph.D.4

The wrong foods at the wrong time will sabotage your efforts in the gym and be detrimental to your waistline. Stop wasting your hard training. Your body is primed for massive muscle gain and fat loss with this dietary protocol. Through intelligently programming your diet and disciplined eating you’ll add slabs of muscle – without a side of love handles.

Continue to Part Two: The Lifting Program

References:

1. Andrews, R. “All About Nutrient Timing.” Precision Nutrition . Precision Nutrition Inc.. Web. Accessed 11 Nov 2013

2. Berardi, J. , and Ryan Andrews. “The Essentials of Sport and Exercise Nutrition.” 2nd. Toronto : Precision Nutrition Inc., 2012. 115. Print.

3. Berardi, J. , and Ryan Andrews. “The Essentials of Sport and Exercise Nutrition.” 2nd. Toronto : Precision Nutrition Inc., 2012. 358-361. Print.

4. Ivy, Ph.D., J., & Portman, Ph.D., R. (2004). “Nutrient timing.” Laguna Beach : Basic Health Publications Inc.,2004. 48-51. Print.

5. United States Department of Health and Human Services. “Insulin Resistance and Prediabetes.” Bethesda, MD: , 2013. Web.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.