In the previous installment I addressed conditioning progression and gave examples of programs. When it comes to strength training, progression is many times shoved aside. I believe if more people paid attention to strength training progression there would be more muscle roaming the planet.

In the previous installment I addressed conditioning progression and gave examples of programs. When it comes to strength training, progression is many times shoved aside. I believe if more people paid attention to strength training progression there would be more muscle roaming the planet. It’s pretty simple: force your muscles to do more over time.

The following bit of advice will take ANYONE a long, long way to achieving goals:

Lift the resistance for as many good repetitions possible. Record the number of repetitions achieved. Attempt to do more in the next workout.

How difficult is that to comprehend? It isn’t, however due to the information overload that exists out there, it can become over-complicated, especially with progression plans that use the antiquated percentage system. The percentage system uses various percentages of a one-repetition maximum (1RM) for a specific number of repetitions (reps). In short, you determine the maximum amount of resistance you can lift one time (1RM), then you use that figure to base your future workouts on. Examples:

- 3 x 10 @ 75% – Three sets of 10 reps at 75% of the 1RM

- 8/80%, 6/85%, 6/85%, 4/90% – Eight reps at 80%, two sets of six reps at 85%, and four reps at 90% of the 1RM

These examples at least offer some type of guidelines for lifting. The percentage system, however, has major flaws for these reasons:

- Genetic differences. Due to a host of genetic differences between people, there is no accurate way to determine a perfect number of repetitions for a specific percentage. That is, if 80% of a 1RM for eight reps is the prescription, it could be unattainable for one person, dead-on for another, and not challenging for a third person. A number of studies (1 or 2, to note a few) have shown the variance in rep possibilities with various percentages of a 1RM. Can you see the confusion this can create, especially in multiple-set protocols?

- Intensity interpretation. Proponents of the percentage system consider “low” intensity to mean percentages around 60% of the 1RM and “high” intensity to mean around 90% of the 1RM. Not to go into a diatribe here, but this is too subjective and arbitrary. Please understand a variety of resistances can be used to overload muscle. 60% of a 1RM can be effective if it challenges (fatigues) the muscles. And if it indeed challenges the muscles – that is, is used intensely to create an overload – would this not be considered high intensity? So, toss out the ridiculous intensity labeling of percentages of a 1RM. Heavy resistance can be high intensity and relatively lighter resistance can be high intensity. It all depends on how hard you work with them.

- There is no place for low intensity in the iron game. If a plan suggests a low-effort day as a back off or recovery day, then just take a day off and let the body heal. Training half-assed is un-measurable. It is a subjective and a wasted activity based on some pseudo-guru’s opinion. To stimulate muscle tissue one must work hard. A wide spectrum of resistances can be used to fatigue and overload muscle provided objective, measurable effort is exuded.

- Rep speed. Real-life example: the objective is 82.5% for eight reps. Joe Schmoe uses poor form – bouncing, jerking, heaving, and squirming – and gets the eight rep goal. John Doe uses impeccable form – a slower controlled movement, no momentum, optimized muscle activation – but only obtains six reps. What data do they record? What about the next set or next workout goal based on the result of this set? Should John Doe then use lousy form to get the required reps? Do you see a problem here?

- Periodization nonsense. Many have been sucked into the embarrassingly complicated verbiage of periodization. Periodization originated in former Eastern Bloc (and drug assisted) Soviet Union and East Germany in the 1970s. Periodization is essentially a sexy word for variation. Periodization is characterized by training periods broken down into microcycles, megacycles, and mesocycles. Within these cycles is the anticipated development of strength, speed-strength, starting-strength, strength endurance, speed endurance, power, power endurance, blah, blah, blah. These qualities are purportedly attained via various exercise prescriptions based on specific set/rep/% scripts. Understand most of this is unsupported by legitimate science, primarily due to the variance of the percentages of a 1RM, one’s genetic make-up, and the reality of how we contract muscle (see Henneman’s Principle).

Okay, rant mode off. It’s time to make you happy with a progression tool that is simple to understand, very productive, but highly underused: the repetition range. As opposed to the unpredictable and inaccurate percentages of a 1RM, rep ranges use a range of reps to provide reasonable progression. In example, a 10-14 rep range would entail the selection of a resistance where at least 10 repetitions could be performed but no more than 14 when the exercise is taken to the point of volitional muscular fatigue (VMF).

In example, if 150 pounds where used and 12 reps were perform to VMF, that is, a 13th rep was unable to be performed, 150 x 12 would be documented. Because the 12 reps fall within the 10-14 range, the goal in the next workout would be to obtain at least 13 repetitions with the 150 pounds. If a 13th rep (or more) is obtained, it would represent improvement. Remember, strength increases occur in small increments at a time, and a one-rep improvement is how they are accrued. When the upper end of the range is obtained, the goal in the next workout would be to increase the resistance reasonably (i.e., five to ten pounds – 155 or 160) and attempt to achieve at least the 10-rep minimum in the 10-14 range.

Rep ranges are a no-brainer. Let me explain why:

- Rep ranges account for variations in genetic variability due to the wide range of repetitions possible with different percentages of a 1RM. It does not matter what the exact percentage is with rep ranges. Using 80% of a 1RM may result in 8, 9, 10, or 11 reps. The only thing that matters is what was obtained at that point in time.

- Rep ranges can be varied for different cycles such as heavy, moderate or light resistance exercise protocols. This can mirror traditional periodization plans if one seeks that route. Heavy could be rep ranges of 2-6 or 4-8, moderate might be 6-10 or 8-12, and light could be 10-14 or 12-16 reps.

- Rep ranges are objective. They show you exactly what to do in forthcoming workouts to assure progression. Perform 150 x 13 in a 10-14 reps range? The goal would be 150 x 14 or more in the forthcoming workout. If 14 reps were achieved, the resistance would then be increased and the goal would be the minimum of 10 reps in the next workout. Very objective and simple to understand.

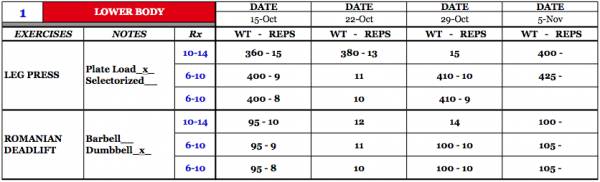

- Rep ranges do not require exasperating thought when creating a training plan, even when using multiple sets. Here is an example over four workouts:

Click on image to enlarge

Remember, if you’re increasing your ability in resistance and/or repetitions over time, you are increasing your strength, power, and endurance. If you do not believe me, re-read any legitimate physiology textbook. I will expound on this in a future article if you seek more legitimate science on this topic. Happy training to all of you!

But what if you are a spacing out on cardio? Check out: