If foam rolling and flossing is the extent of your mobility practice, we’ve got some work to do. It’s easy to brush off your mobility training for sexier things like lifting heavier or flooding Instagram with sunset handstand pics, but improving mobility should be a cornerstone of your program.

In this article you’ll learn:

- How critical mobility is both in and out of the gym

- Why it deserves a bigger emphasis in your training

- How to get started today

It’s More Than Semantics

Let’s clear the air right off the bat. I’m not going to get into the mobility versus stability debate because it’s a false dichotomy. It all comes down to control and coordination (we’ll talk about that below). First, let’s get clear on what mobility is and is not. Let’s use the example of my skeleton model to demonstrate.

He has fantastic range of motion. That’s flexibility. There are no tissue or neural restrictions preventing him from achieving all sorts of contortions. But he has terrible mobility. His joints are unstable and can’t hold themselves in position. He can’t move in between new positions. In every sense of the word he’s immobile.

Why is that? Control and coordination.

Mobility In A Dynamic System

You might remember that movement is a pretty complicated thing, almost a lucky accident happening beyond our control. Each of our movements is a solution to a complex problem. The “rules” of the problem are called constraints. Typically, they fall into three categories:

- Task

- Environment

- Organism

Task constraints involve exactly what you’d imagine. Pick up an object of X pounds. Carry it Y distance. If the task at hand requires moving a boulder, picking up a pebble doesn’t follow the rules. Environmental constraints are equally intuitive. What sort of environment are you performing this task in? This could involve varied textures and terrain, or social factors like peer pressure or support.

Note how you can’t do a whole lot about those first two constraint types. That’s where the organismic constraints come into play. These involve strength, mood, fatigue, and the like. When you combine these constraints, you get something like this happening:

Any and all of our movements emerge out of this complex interaction.

Mobility plays a key role here. We can think of mobility as our movement potential. It’s the key constraint on what options we have access to. Improve control and coordination of your joints in increasing ranges of motion, and you radically expand what you’re capable of.

What mobility does is widen the box. It gives us more options, and it makes us a more resilient, adaptable beast. Cardio doesn’t do that. Strength training doesn’t (always) do that. Mobility is like the compound interest of the movement world. Consistently put a little bit in, and you can expect geometric growth.

Here’s the thing: It takes a hell of a lot more than just stretching and foam rolling to improve your mobility. Those might improve your flexibility (range of motion), but they don’t do much to teach your body how to put that range of motion to use. They have nothing to do with improving coordination and control.

Control Yourself

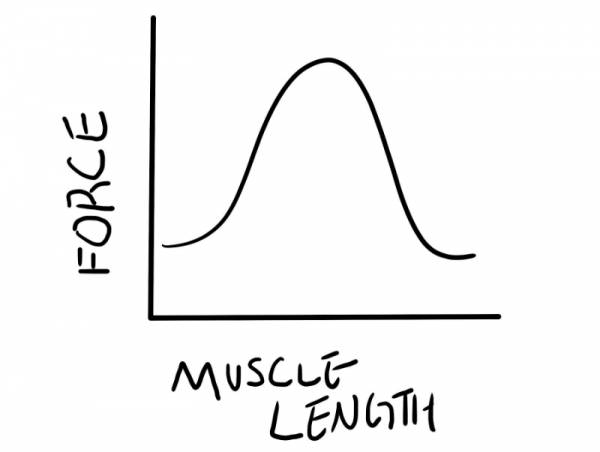

Speaking of coordination and control, you may have come across an image like this before:

It’s a rough representation of how muscles work. They can generate force well around the middle of their range of motion, but they lose their oomph as they lengthen or shorten, and they drop off significantly at extreme ranges.

Now a lot of trainers and coaches out there forget that this is only a trend, not a rule. Hence the rampant and needless reductionist trend toward partial reps. We seem to forget that we’re working with an adaptable living organism. If that graph was a strict rule, then we wouldn’t have fun things like gymnastics and jiu jitsu.

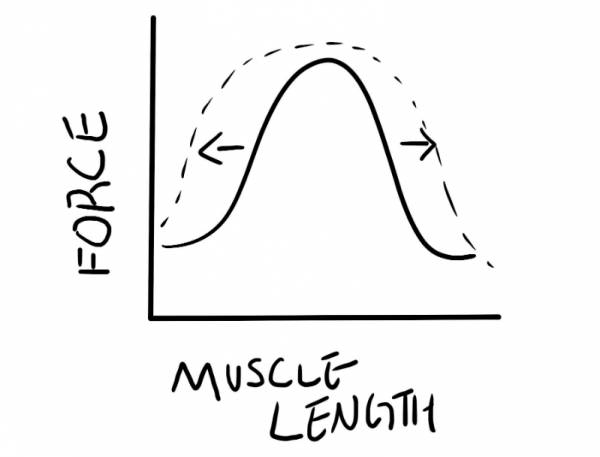

Your body can and will physiologically shift to respond more efficiently to given demands. If we tell our elbow that it needs to be stable and strong in extension, our connective tissues—ligament, tendon, and muscle—will adapt. When we do that progressively over time, we make the curve look more like this:

We teach that biological stuff how to organize more effectively and efficiently in response to a wider array of demands. This is cool. This is what gives us more options. And it’s exactly why you should be focusing more intently on your mobility practice.

It’s Not Voodoo

For some reason, we get confused how to improve mobility, as if it’s immune to the basic rules of biology. But it works the same way as anything else you train, and it follows two rules:

Let’s use a couple of examples here to demonstrate. You don’t train for sprints by running 10k at a time. You don’t bench to improve your deadlift. You sprint, and you deadlift. Of course other things come into play, but in general our bodies get good at the things we do with them most frequently and consistently. There’s a bit of transfer between strength skills, but specificity is key.

Similarly, you don’t start day one of marathon training by running 22 miles. And you don’t start under the bar with a 300 pound squat. We have to give our system time to adapt to a progressive load.

Mobility is no different than any other element of training.

You don’t improve your shoulder flexion by emphasizing ankle dorsiflexion, and you don’t hop into splits on day one. You train specific strength within specific ranges of motion, and you do it consistently over time. In functional range conditioning we do this by:

- Expanding range of motion of a given joint

- Controlling that range of motion through nervous system and soft tissue conditioning

- Creating movement potential by moving through more and more complex articulations

Put more simply: increase your range of motion, and then teach your body what to do with that range. No foam rollers, tape, or toys necessary.

The really cool thing is that you can do this every day. Unless you tank your nervous system on boatloads of stress, it’s capable of quite a bit of adaptation on a daily basis. We call this learning. Soft tissues will take a bit more time to adapt, but if you program it well (hint: get a coach), mobility can improve rapidly without adversely affecting your other training.

Get Started

Here’s a safe rule of thumb: If it’s able to move, move it as much as it’s able as frequently as you’re able. Have a neck? Move it as much as you’re able to (barring pain or specific limitations, be smart with yourself).

How about toes? You’ve likely got a few of those. Move them. Your knees and low back will thank you.

I’ll go out on a limb and say that if you get your neck to work like a neck and your toes to work like toes, then you’ll find a lot more ease in just about all of your other movements. Why? Because your body is a master of compensation. When the neck and toes are unable to control and coordinate, everything in between is forced to pick up the slack.

Now this is pretty simple in theory, but it’s not easy. It’s some of the most difficult work you’ll ever do. Your job is to actively hunt for those angles and positions where your body doesn’t know what to do. You will cramp, and that’s ok. Better to find out you can’t control your ankle now, than when you’re forced into an unfortunate position when you stumble on a run.

If You Aren’t Improving, You’re Diminishing

You have a choice. You certainly don’t have to do any of this. You can move like a sagittal plane robot for the rest of your life, if that’s what you want. But if you want to be a capable, versatile, resilient human specimen, you owe it to yourself to make mobility a cornerstone of your practice.

Where are the liabilities in your range of motion?

How to Assess Your Full-Body Flexibility

Headline photo credit: Tony Alter | CC BY 2.0