Creating a long-term plan for movement and health can be a bit daunting. There’s so much information available today that many people just don’t know where to start. What should you prioritise? Should you be going running or lifting weights? And how many times a week should you train?

Creating a long-term plan for movement and health can be a bit daunting. There’s so much information available today that many people just don’t know where to start. What should you prioritise? Should you be going running or lifting weights? And how many times a week should you train?

These questions become increasingly important as we get older and there are greater demands on our time. However, it is always worth remembering that the long-term benefits of prioritising health and movement are huge. Yes, leaving work thirty minutes earlier to walk home might make you feel guilty because of the emails you didn’t respond to; however, people who are more active have greater wellbeing, are more productive at work, and have healthier children.1, 2, 3

A Simple Solution

With that and a myriad of other health benefits in mind, I concocted the great upside-down movement pyramid as a way to help you prioritise your approach to better movement.

The great upside-down movement pyramid.

Over the next few weeks I will present a progressive plan detailing why you should sit less, walk more, move stuff, move really quickly, and move for a long period of time, in that order of importance. Each level of the plan will build on the first to add layers of additional movement to your week, but give you time to put each level into practice. As before – if you’re not managing to do the level above, don’t do the level below. After all, you’ve got to stand before you can walk.

Sit Less

In case you hadn’t heard, sitting is the new smoking.4 This may sound melodramatic (after all, we all have to sit), but in terms of the effects on our overall health, there is truth to it. For example, a recent meta-analysis found a 5% increase in the risk of dying (overall mortality) for every additional hour spent sitting per day – after taking physical activity into account.5 If we turn this around, people who spend more time standing also appear to have a reduced overall mortality.6

“Prolonged periods of sitting can negatively affect the way the arterial wall functions, which is directly associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.”

However, out in the real world, we often need to sit to work. Although standing desks have become increasingly popular, it’s important to note this may not be much better. Standing at a desk doesn’t prevent you from being hunched over a screen, and prolonged periods of standing in one place can also cause things like varicose veins and back pain.17,18

So What Should We Do?

As you’re probably reading this to procrastinate whilst at work, let’s do the advice bit first, and those who are interested can stick around for the science at the end.

During your commute: If you use public transport, don’t take that seat. You don’t need it. You can even take it up a notch by minimising the use of support rails. Yes, you’ll look silly surfing the bus, but it’s surprisingly fun!

At work:

- Stand (or walk) while you take phone calls or if you need to think.

- Go and find that colleague rather than sending him or her an email. You’re much more likely to get a positive response, and you may even make a friend.

- Relocate for lunch. Better yet – take it outside.

- When sitting, move position frequently, or (quietly) tap your feet to get your blood moving.

- Get up regularly, or at least once an hour. Do a lap of the office, pop outside, or take the stairs. Need reminding? Plenty of free apps and programs are available to nudge you out of your chair.

- Got like-minded colleagues? Stick a pull-up bar on your office door and do a couple of reps as you go in and out.

Instead of staying in the office, head outside for a walk to catch up on calls and texts.

At home:

- It’s okay to relax after a long day, but try not to immediately slip into a coma on the sofa, only to reappear just before bed time.

- Keep getting up, or at least move position regularly.

- Do a few push ups during TV ad breaks. No matter how many times they recommended this in fitness magazines, I’m still not sure anybody does it.

- Do your ironing and other chores while you’re catching up on Britain’s Got Talent and Biggest Loser. That will give you more time to enjoy your weekends.

- The minutes just before and after dinner are a great time to get up, or get out of the house for a quick walk.

The real moral of the story is to focus on minimising the amount of time you spend in one position, rather than to demonise sitting specifically.

What’s the Deal With Sitting?

If we want to dig into why sitting is so bad for our health, three different (and almost certainly connected) mechanisms are important – inflammation, insulin resistance, and blood flow.

“When we’re talking about cardiovascular disease (such as heart attacks and strokes), the big problem stems from atherosclerosis – calcified ‘plaques’ that build up in the walls of our arteries.”

While everybody was worried about cholesterol, the role of inflammation and insulin resistance in the development of heart disease, obesity, type-2 diabetes, and many cancers flew under the radar for decades. However, we’re now seeing that markers of inflammation predict the risk of heart disease better than cholesterol, and if your insulin levels are low (indicating a high insulin sensitivity), then your cholesterol levels become pretty much irrelevant.7,8,9,10

Why the random trip down biochemistry lane? Because inflammation, insulin, and insulin resistance all increase with time spent sitting.11 Uh oh.

Are You Sitting Comfortably?

In reality, we don’t have any proof that sitting directly causes insulin resistance. Perhaps people who are insulin resistant suddenly have a desire to sit more. It’s unlikely, but possible. Therefore we need to look at other pieces in the puzzle, such as the way in which our blood flow changes when we sit.

When we’re talking about cardiovascular disease (such as heart attacks and strokes), the big problem stems from atherosclerosis – calcified “plaques” that build up in the walls of our arteries. These can rupture, causing a blockage. Alongside things like inflammation, the way in which blood flows through our arteries affects the development of atherosclerosis. When the flow is disturbed or redirected, it puts extra stress on the arterial wall. This is why we see atherosclerosis build up in places like carotid arteries in the neck, because the artery splits into two early on, with increased turbulence at the split point (also known as the bifurcation).12 However, your arteries need some stress in order to work properly, and reducing flow can have a negative effect on arterial function.

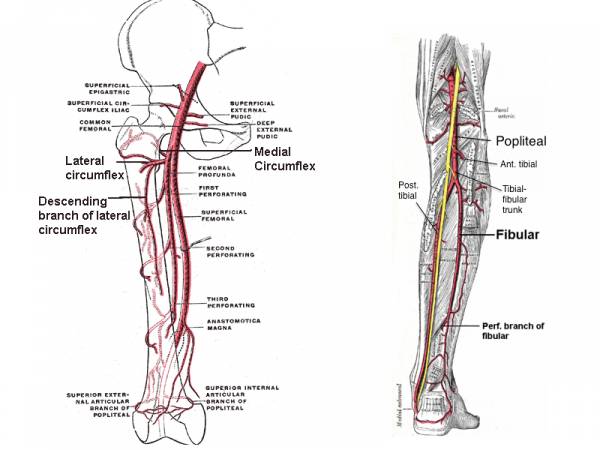

When we sit, we bend at the hip and the knee, which reduces flow in the femoral and popliteal arteries, respectively.13,14

Left: Femoral arteries; Right: Popliteal arteries

Prolonged periods of sitting can negatively affect the way the arterial wall functions, which is directly associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.15 That change in flow caused by prolonged sitting is potentially why those arteries in the legs are a common place for atherosclerotic plaques to occur. We even see these patterns of atherosclerosis in 4,000 year-old Egyptian mummies!16 If you were important enough to have your body preserved, you probably got to spend a lot more time sitting compared to everybody else.

Start With Your Daily Routine

Conjecture about mummies aside, there’s good evidence for minimising your sitting time as much as possible. Try to work as many of the ideas above into your daily routine. That will line you up perfectly up for your next step(s) to better health – walking more.

More Like This:

- Walking: The Most Underrated Movement of the 21st Century

- 4 Office Exercises No One Will Know You Are Doing

- Having It All – Strength Gains in the Office

- New on Breaking Muscle UK Today

References:

1. Puig-Ribera et al.. Self-reported sitting time and physical activity: interactive associations with mental well-being and productivity in office employees. BMC Public Health. 2015 Jan 31;15:72.

2. Sears et al.. Overall well-being as a predictor of health care, productivity, and retention outcomes in a large employer. Popul Health Manag. 2013 Dec;16(6):397-405.

3. Robinson et al.. A narrative literature review of the development of obesity in infancy and childhood. J Child Health Care. 2012 Dec;16(4):339-54.

4. Is sitting the new smoking? New science, old habit. Mayo Clin Health Lett. 2014 Oct;32(10):4-5.

5. Chau et al.. Daily sitting time and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013 Nov 13;8(11):e80000.

6. van der Ploeg et al.. Standing time and all-cause mortality in a large cohort of Australian adults. Prev Med. 2014 Dec;69:187-91.

7. Ridker et al.. Relation of baseline high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level to cardiovascular outcomes with rosuvastatin in the Justification for Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER). Am J Cardiol. 2010 Jul 15;106(2):204-9.

8. Yanase et al.. Insulin resistance and fasting hyperinsulinemia are risk factors for new cardiovascular events in patients with prior coronary artery disease and normal glucose tolerance. Circ J. 2004 Jan;68(1):47-52.

9. Després et al.. Hyperinsulinemia as an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1996 Apr 11;334(15):952-7.

10. Bartnik et al.. Abnormal glucose tolerance–a common risk factor in patients with acute myocardial infarction in comparison with population-based controls. J Intern Med. 2004 Oct;256(4):288-97.

11. León-Latre et al.. Sedentary lifestyle and its relation to cardiovascular risk factors, insulin resistance and inflammatory profile. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2014 Jun;67(6):449-55.

12. Chiu and Chien. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2011 Jan;91(1):327-87.

13. Schlager et al.. Wall shear stress in the superficial femoral artery of healthy adults and its response to postural changes and exercise. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011 Jun;41(6):821-7.

14. Restaino et al.. Impact of prolonged sitting on lower and upper limb micro- and macrovascular dilator function. Exp Physiol. 2015 Jul 1;100(7):829-38.

15. Bruno et al.. Intima media thickness, pulse wave velocity, and flow mediated dilation. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014 Aug 23;12:34.

16. Thompson et al.. Atherosclerosis across 4000 years of human history: the Horus study of four ancient populations. Lancet. 2013 Apr 6;381(9873):1211-22.

17. Pfisterer et al.. Pathogenesis of varicose veins – lessons from biomechanics. Vasa. 2014 Mar;43(2):88-99.

18. McCulloch et al.. Health risks associated with prolonged standing. Work. 2002;19(2):201-5.

Photo 1courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 byHäggström, Mikael. “Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014”. Wikiversity Journal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.008. ISSN 20018762. (Image:Gray548.png) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 by Bakerstmd (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons.